A new report by the International Broadcasting Trust (IBT) looks at how fake news is affecting the charity and humanitarian aid sector, and hopes to change how NGOs disseminate media content.

By Carolina Are

The IBT’s report on fake news explores the link between inaccurate or misleading journalism and the loss of trust towards NGOs and the charity sector. It gathers examples of fake news from across the sector, from malicious fabrications about individuals through to attempts to sway public attitudes against rescuing of refugees.

The Impact of Fake News in the Humanitarian Sector

Like political institutions and the media, the charity sector has experienced a decline in trust in recent years. High profile controversies, such as the sexual misconduct scandal surrounding Oxfam in Haiti, and the Red Cross’ loss of £3.8m of fundraised money to tackle Ebola in West Africa, have seriously undermined the trust and credibility of international aid agencies in the eyes of their audiences.

Against this backdrop, fake news and misinformation about NGOs originating from social media rumours have raised significant new challenges.

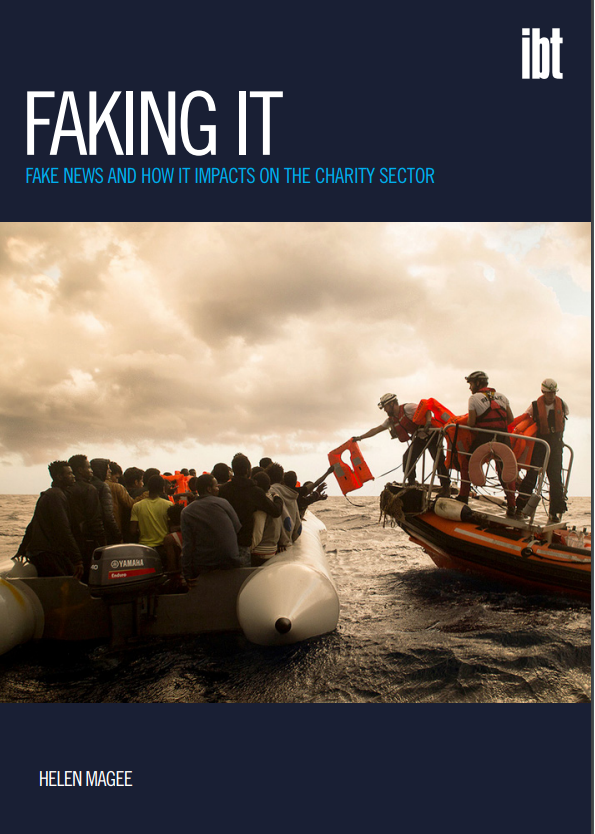

Immigration issues, in particular, have provoked polarised views in both mainstream and social media. NGOs working in search and rescue operations in the Mediterranean, for example, have been subject to fake news stories deliberately designed to undermine their activities. Some of these accusations have gained traction in mainstream media and have helped to create a climate of mistrust towards the NGO sector, the IBT report argues.

Fake News

Audiences are increasingly getting their information from online sources. Yet a Channel 4 survey conducted in February 2017 found that only 4 per cent of respondents could spot fake news online. Quoting First Draft, the US-based verification network founded in 2015, the IBT report provides a typology of misleading information. The authors distinguish between:

- False connection – headlines and captions don’t support the content;

- False context – genuine content shared with false contextual information;

- Manipulated content – genuine information or imagery manipulated to deceive;

- Satire or parody – no intention to cause harm but potential to fool;

- Misleading content– misleading use of information to frame an issue or individual

- Impostor content – impersonation of genuine sources;

- Fabricated content – content that is totally false, designed to deceive and harm.

New Measures to Reduce Fake News’ Impact

NGOs need to gain and retain trust to convince the public of the value of their work, the report argues, and the polarised debates that dominate social media, alongside this misleading information, can be a major obstacle.

Quoting Fergus Bell, who has done training and consultancy work in the aid sector, the report states that NGOs face a two-fold problem.

“1. They have to verify information on the ground that will help them determine where it’s safe or unsafe to operate…

2. …But they are also bearing the brunt of misinformation and fake news about their ground operations. They need to monitor the information that is shared about them and, where they are the subjects of fake news, they need to recognise it and fix it. This is difficult because fake news spreads so quickly.”

The report states:

“Only strong communication strategies, built around clear core values, will ensure that NGOs are heard above the increasing stridency of competing voices on platforms like Facebook and Twitter. […]

Openness, accountability and inclusivity are key. Regulation of social media platforms is very much on the political agenda, but so far they have avoided the type of regulation that controls the mainstream media by insisting on their role as intermediaries rather than publishers or news organisations.”

IBT’s research provides suggestions for how NGOs, states and key players can counteract the influence of fake news in the humanitarian communications space. These suggestion focus on: regulation, fact checking, verification and media literacy.

Regulation

To date, social media platforms have avoided the type of regulation that moderates mainstream media by insisting they are intermediaries rather than publishers or news organisations. However, as the problem of fake news has become more urgent (in light of claims about Russian involvement in the US election, for example) social media platforms might soon be obliged to take action.

In its submission to the Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Select Committee Inquiry into Fake News, Facebook described the introduction of an initiative involving the ability to flag up items that are fake. In its submission to the same inquiry, Google introduced Google News Lab, a team dedicated to collaborating with and training journalists around the world in order to prevent fake news, together with the launch of fact check labels allowing publishers to highlight fact-checked content.

The report states that, although these initiatives are welcome, “[t]he problem is the lack of any consensus within the digital industry on what self-regulation implies and it remains to be seen how effective these measures will be.”

Fact-checking

The growth of fact-checkers has spiralled since the spread of fake news online – however, the efficacy of their work is still being debated. The IBT report suggests that aside from being accurate in their communications, NGOs should be more transparent about their sources and methods of authentication to build trust with the media:

“This transparency extends to NGOs accepting when they get something wrong and admitting when they don’t know something as much as when they do.”

However, fact-checking has its critics. BuzzFeed’s Craig Silverman raises doubts about the efficacy of these services based on how people respond to information:

“When people create the false stuff they know that it needs to appeal to emotion. They know that maybe if it can have a sense of urgency, if it can be tied to things people care about, that’s probably going to do well. Whereas when you come in as the debunker, what you’re doing is actively going against information that people are probably already willing to believe and that gets them emotionally.”

Verification

NGOs should be trained not to retweet – or not to spread unauthentic or unverified information in a spur-of-the-moment action. Discussing Sam Dubberley ‘s work with Amnesty’s Digital Verification Corps, the report shows how aid workers can contribute towards sharing authentic and reliable content: “NGOs with half a day’s training on social media see awful photos and retweet. […] Some basic training will avoid 90% of these mistakes.”

An important verification tool is conducting reverse image searches by right clicking on an image and selecting “search for image,” revealing other places on the internet where the photo has appeared. For instance, at the end of November 2017 the BBC reported on the attack on Al-Rawda mosque in Egypt’s North Sinai province, which resulted in at least 235 fatalities. However, the images appeared on the Al-Araby news site to illustrate this attack were false. A reverse image search showed that one picture showed the aftermath of a bomb attack in another Egyptian town in 2015 by checking the surroundings seen in the image.

Media literacy

In the UK, Ofcom’s most recent survey found that 28 per cent of 8-11 year-olds and 27 per cent of 12-15s assume that if Google lists a website then they can trust it. Only 24 per cent of 8-11s and 38 per cent of 12-15s correctly identified sponsored links on Google as advertising.

Interviews published in the report stressed the need to educate young people in media literacy as part of their school curriculum in order to distinguish between news, opinion and bias.