The second meeting of the LEaDER journal club was opened by Rachael-Anne Knight (SHS) who set the scene for the discussion around the Growing Access to Lecture cApture (GALA) project, which is taking an evidence-based approach to updating City’s lecture capture policy.

The two papers discussed focussed on both staff and student perspectives of lecture capture and the group agreed with the comment that it was nice to hear some positive perspectives about lecture capture and what it can do for us, rather than the usual focus on ‘to use or not to use lecture capture’.

Lecture capture in higher education: time to learn from the learners

We started with the paper from Nordmann and McGeorge (2018) which presented a review of lecture capture policies and a literature review of the pedagogic benefits of lecture capture. The dual focus of the paper meant that it came across as a bit of a mash-up of two papers and lacked a clear definition of the methodology. It was also unclear how the two aspects of the paper were linked, however we liked both outputs – especially the tips for writing a lecture capture policy.

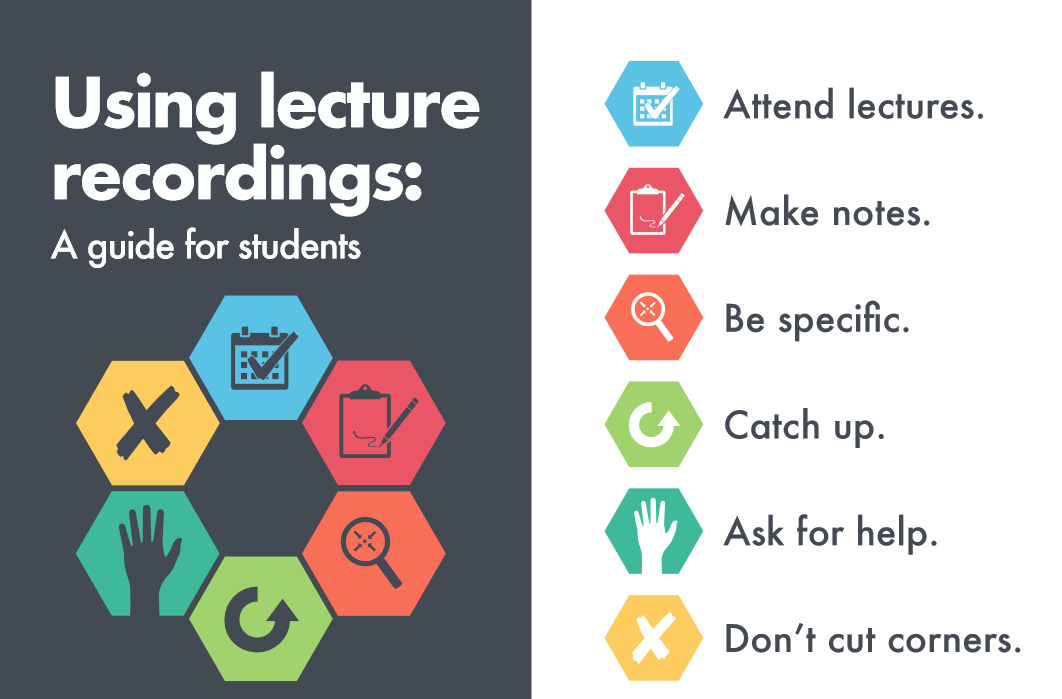

We appreciated that the work took a pedagogical focus and was situated in broader frameworks of pedagogy, such as cognitive load theory and distributed practice. It also emphasised the benefits for students with a focus on inclusivity. We discussed an interesting finding about lecture capture supporting transition for non-native speakers of English and its role in reducing anxiety amongst studenst who no longer feel under pressure to write down everything the lecturer says. LEaD’s Academic Learning Support team run workshops on note-taking for students and the paper emphasised the need for critical thinking in note-taking and best use of lecture capture to support deep learning. An interesting comment was that ‘no one is an academic English native speaker’ and that lecture recordings can help new students to understand how lectures work. We discussed the importance of providing guidance to students about how to use lecture recordings, not binge watching, and noted the useful student guidance created by the University of Glasgow. We also looked at how academics talk to their students about the use of lecture capture and noted the importance of managing expectations about production quality, given students are used to seeing high quality videos via YouTube and other sources.

We felt that at City we need to be more explicit about where things like lecture capture can be used more effectively to benefit students and to make the link with other work taking place in the institution, such as supporting commuter students and student attainment.

Big brother or harbinger of best practice: Can lecture capture actually improve teaching?

The second paper by Joseph-Richard et al. (2018) focussed on teacher perspectives, which are under researched in the literature. The paper mapped the findings against the UK Professional Standards framework (UKPSF) however it wasn’t clear why they had done this as they had only mapped against areas of activity and didn’t refer back to the UKPSF in the discussion. We felt that they could have also explored mappings to the knowledge and values aspects of UKPSF, especially inclusive teaching.

In terms of the findings, the authors suggested that lecture capture “crushes spontaneity” and suggested that lecturers are more aware of what they are saying and as a result might change their tone and teaching persona. We queried accountability for saying something in a lecture recording and the potential for something to be taken out of context. We agreed that being able to edit recordings can help here, as well as knowing when to use the pause and resume functionality available in DALI learning spaces.

We also felt that the paper focussed primarily on lectures, with some mention of student presentations, and would have benefitted from exploring other uses of lecture capture beyond just recording live lectures. One interesting example mentioned in our discussion was lecturers using a ‘nudge approach’ to send students key highlights of the lecture recording 2-3 days after the lecture to prompt them to revisit it. We also discussed concerns about the finding of using lecture recording for “holding students more accountable in group tasks” as it may bring about participation for fear of being punished. The paper also raised the suggestion of lecture capture not being inclusive for all, in particular hearing impaired students, and discussed the need for transcripts of recordings.

In conclusion

Rounding off the discussion, it was suggested that in the future we might look back at these discussions about not using lecture capture and think them to be quite quaint as it will have become the norm. The question for us is how do we make it become the norm and are lecturer perceptions of lecture capture changing? What role do students have in facilitating this change? Students already ask whether recordings are taking place and it’s felt that using lecture recording is a ‘quick win’ for getting students on your side.

The paper prompted discussions about research at City to better understand staff motivations for lecture capture. This has been covered in part by a LEaD project which has fed into the GALA project, but would be good to link these findings into the policy and any promotion of lecture capture.

Further reading

Sarsfield, M., & Conway, J. (2018). What can we learn from learning analytics? A case study based on an analysis of student use of video recordings. Research in Learning Technology, 26. https://doi.org/10.25304/rlt.v26.2087