A couple of years back I gave a talk during #citymash entitled ‘NSFW: Fanfiction in the Library’, which was more or less an exploratory dive into how LIS can learn from fan information behaviour. (My original blog post on this event can be found here. You can also read the handout for the talk here).

Recently I found the notes I took from audience members during the talk, which were very helpful in helping formulate some of the theories later developed in my PhD thesis. I’ve decided to do a little rundown of these notes (plus some discussion), which might be of interest, particularly to those who are thinking about what LIS can learn from fan information practices (and that of other participatory cultures. Trust me – there is lots we can learn!).

So here we are – some comments from the audience

-oOo-

Fan information behaviour is fun.

The implication being that information behaviour in professional/academic/research/mundane contexts is not. Is this strictly true? If not, how can LIS make their systems fun for users to engage with? If yes, then what can we do to harness the pleasurable aspects of information behaviour that we are not already tapping into?

Tagging only makes sense to me.

One audience member thought that the only aspect of fan information behaviour that could be successfully incorporated into LIS systems is tagging. But free tagging has already been instituted on many online library, museum and gallery catalogues, with only limited success, and hasn’t seen the wide-ranging and innovative usage that manifests on platforms such as AO3 and Tumblr.

You need a feeling of community for it to work.

Users need to have a strong sense of community; they need to be invested in the institution and/or the thing that it stands for. Otherwise they will not be motivated to contribute to participatory classification activities (such as free tagging), or other initiatives that may be beneficial to institutional information work. Certain groups, such as scholars, amateur genealogists, historians, movie enthusiasts etc., already have the requisite investment in a certain domain – however the degree of their involvement in participatory information behaviour is variable, and whilst similar in some ways to fan information behaviour, is arguably less intense.

Publicity and discussion is needed to foster a sense of community and investment in collections.

Are there people who already have that vested interest in your collection? Who are passionate about it? Find those people and engage with them. What do they have to offer? What do they think are the best ways to publicise your collection and engage others with them?

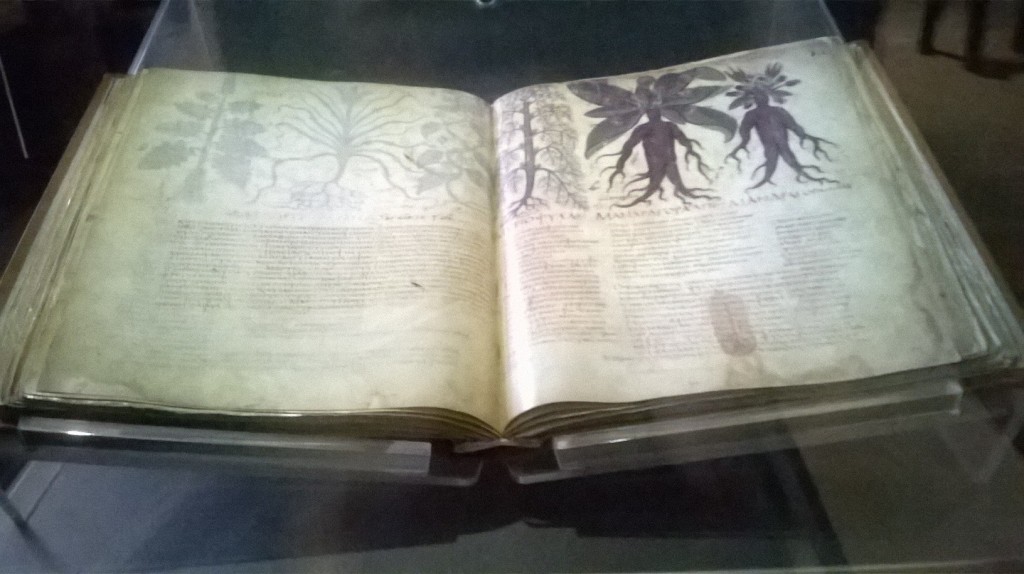

AO3 is creating a collection of deleted fanworks.

Fans are very interested in preserving their cultural history and the artefacts associated with it. They are able to think outside the box and come together on a voluntary basis to preserve their fannish history. Maybe passionate users of memory institution collections have ideas about how works they are interested in can best be preserved, curated and showcased.

There’s a similarity between big name scholars and big name fans (BNF). The cliques that form around BNF and their influence can be toxic to the community. There can be gaming the system, such as getting fans of the BNF to increase hits, reviews and positive spin on their work.

The comment implies that scholarship suffers from the same sorts of problems, such as skewed metrics and citation practices.

Library systems could be more user-focused.

There is a trend towards this, with more ‘interactive’ functions, such as scrolling book covers, free-tagging affordances, and the ability to create reading lists – are these initiatives successful, and do they engender passionate, fan-like information behaviour? How can we make using the library catalogue ‘pleasurable’?

Friction is an issue – there is less friction for fans when using their information systems.

There is plenty of friction in fan information systems, but because fans are invested in the system (and sometimes because they actually own, develop or maintain the system), they are more motivated to create workarounds or improve that system. Perhaps information professionals can engage with users about friction points and how to overcome them.

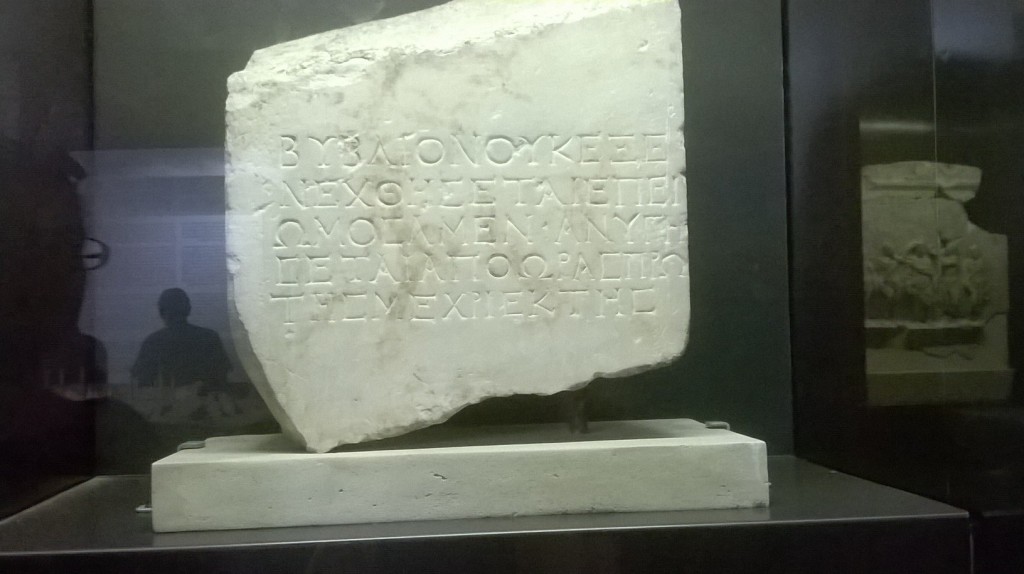

MARC cataloguing – can it be used to catalogue fanworks?

MARC cataloguing standards are not readily transparent and there is a learning curve to using and understanding them. Most people outside of LIS have not heard of MARC or know of its purpose. Similarly, standards such as the Library of Congress subject headings are not granular enough to cater for the specificities of fandom. Therefore fans do not generally use these standards to catalogue their works – indeed, most fanworks have no standard bibliographical data applied to them. Is there a way that those standards can be mapped onto the cataloguing standards that have already been developed by the fan community?

Fan-tagging type systems already exist for ‘normal’ books.

These can be seen in many OPACs or online catalogues, although usage appears to be low. The tagging system on LibraryThing is much more widely used and successful, as the LibraryThing community has a vested interested in their own libraries (and, perhaps, books themselves). They can also contribute obscure information about books, including different editions, acquisition information, and even upload their own covers for books. There is a sense that they are contributing to the catalogue, and enriching the experiences of other LibraryThing users. This is not apparent in standard online catalogues.

-oOo-

So that’s it for the discussions that came out of my talk. Lots to think about. One thing that stuck out to be as I was going back on these was the point that I copied out in bold in the previous paragraph – “enriching the experiences of other LibraryThing users”. I believe this is of primary importance in building participatory information behaviours and systems. It isn’t merely a case of being personally invested in the collection, but also in the community around it. It is about improving, enriching, and sharing accurate and interesting knowledge about the collection with other users who share your passion. It is about contributing value to a community. It is even about sharing your own knowledge capital – I know a really rare fact about a limited edition of this book, and I want everyone else to know I know. I can reference a really obscure comic issue/TV episode in my fanfiction, and I’m going to tag it so everyone else can know I know about it. I live in the road where this photo in this archive was taken, so I’m going to share my personal knowledge of this road to enrich peoples’ knowledge of this place with my own.). Tapping into what users have to offer the entire community, and making them feel that their knowledge is valuable, is key to concepts of participatory engagement in information work.