Every so often a happy coincidence will come the way of every lucky librarian. Mine just happened to come last month, when, having booked a trip to Italy, I discovered that the Colosseum was hosting an exhibition on ancient libraries. This double whammy of ‘relevant to my interests’ (ancient monuments + libraries) was enough to make me feel that somehow the clouds had temporarily parted on my life, and a mighty hand had pointed at me from the heavens, simultaneously declaring “Thou shalt have thy cake and eat it too.”

And so I managed to visit one of the new seven wonders of the world, and visit “The Infinite Library: Sites of Knowledge in the Ancient World” exhibition at the same time.

“The Infinite Library”

What was fortuitous about the whole thing was that I only managed to catch the exhibition by the skin of my teeth, it having been opened in March and closed on 5th October (yesterday, as it happens). Set in the magnificent and awe-inspiring Colosseum itself (on the 2nd floor), it was the perfect backdrop for an exhibition about ancient libraries, writing and knowledge. Its title – “The Infinite Library” (an allusion to “The Library of Babel” by Jorge Luis Borges) – reminds us of the timelessness of the human quest to analyse, organise and disseminate knowledge. We cannot say for sure when libraries truly began – but we can be certain that as soon as humanity began to analyse their surroundings, their world, and what they knew – they attempted to capture it and encapsulate it in some form (Rock paintings? Cave art?). By transporting us directly into the ancient world via a monumental and ruinous setting, the exhibition brought us that one step closer to a time that is far removed from our own, but that is, perhaps fundamentally as well as intellectually, closer than we might think.

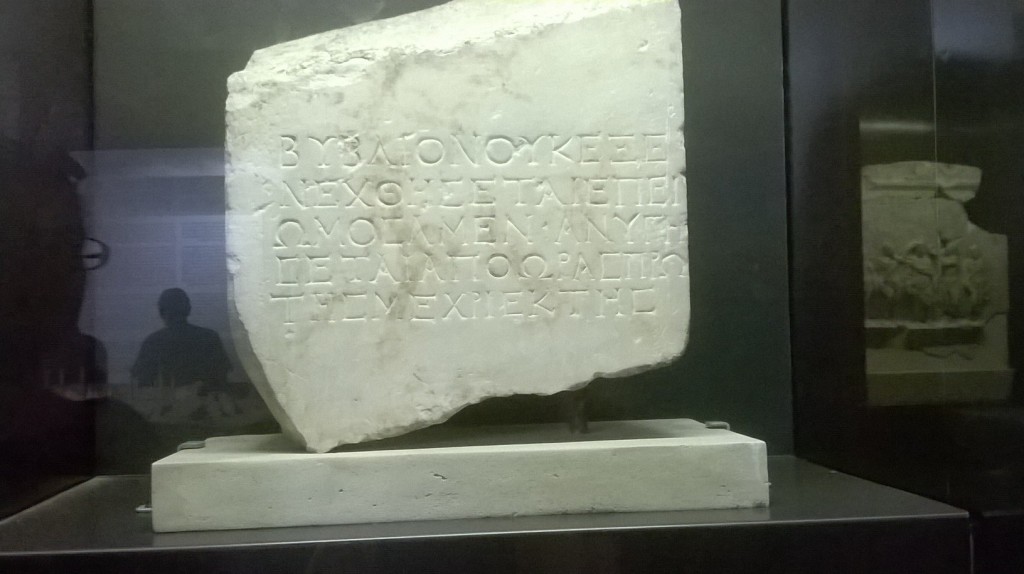

Rules of the library, ancient style.

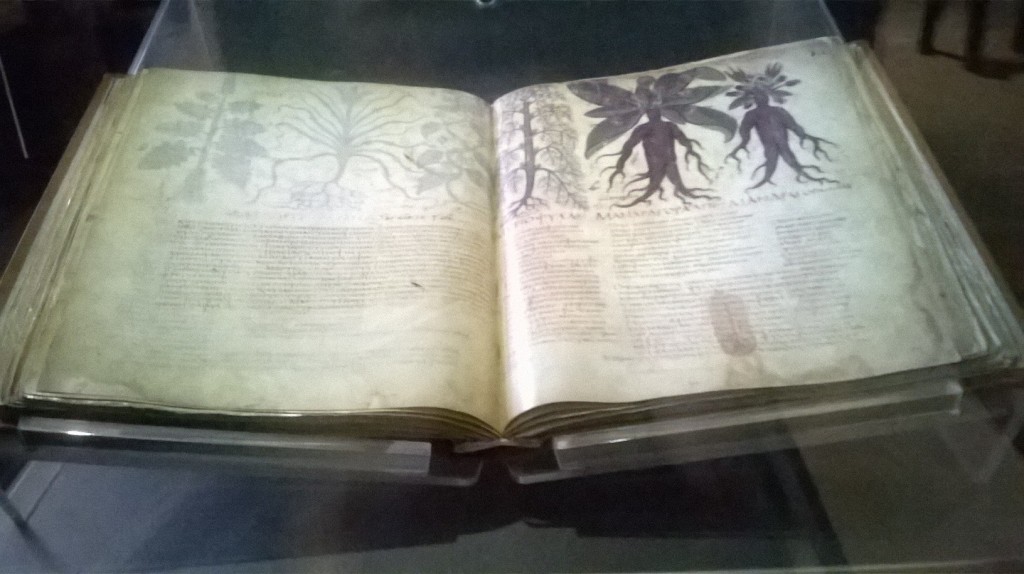

For anyone interested in the history of the library, this exhibition (which was helpfully in both Italian and English) was a beautiful visual counterpart to the many books that have tackled this rich and vibrant subject (Libraries in the Ancient World, The Library at Night, Library: An Unquiet History and The Story of Libraries, to name but a few). Its visual immediacy helped to put flesh on the bones of these texts, to bring the ancient and venerable into the periphery of our vision. Through the exhibits the audience was able to see first hand what actually constituted a book or a document to the ancient Greeks and Romans. Books themselves were a late addition to the ancestral lineage of instantiated documents, and “The Infinite Library” was careful to remind us of this fact. For the ancients, texts were inscriptions, funerary epitaphs, stele, ostracon and scrolls – actual reconstructions of Roman library shelves served to highlight the physical differences between what we might term a library today. Roman book shelves were similar yet strangely unalike – more like niches than shelves, scrolls were stacked inside them horizontally and one could imagine that they weren’t as easily retrievable from their housings as sliding a book out might be.

Holding the exhibition in Rome was fitting in more than one aspect – the Roman world was in itself the birthplace of what we might recognise as the public library (public libraries existed before in ancient Greece, though were restricted to scholars and the literati). Some of these first public libraries were originally part of the bath houses, which may perhaps seem strange to us these days – is a book and bathwater ever a good mixture? But for the Romans, the baths served as the ancient equivalent of the early modern coffee houses – a place where the populous could congregate, gossip, and conduct their business affairs. In this respect, the library was perfectly situated to serve the community.

But it was the similarities to our own libraries of today that gave the visitor cause to smile. Ancient librarians, it appears, had the same concerns our modern libraries do. Amongst the exhibits were included some ancient rules of the library, no doubt exhorting users to silence or threatening reprimands for stealing from the collection; and the human drive to organise was represented, for example, in fragments of a catalogue listing Greek and Roman authors. In this way the exhibition served to bridge the gap between the then and the now, to draw a line of continuity between the past and the present, and to highlight the ways in which the lives of librarians and information professionals has, in the most basic and fundamental ways, remained the same.

What made the exhibition exceptional, however, was its focus not only on the library, but also on the cultural milieu that informed the growth of the library and literacy in the Roman period. For example, it provided a valuable insight into the how the Romans read and wrote. On display were writing implements – styluses, ink pots, tablets, and other writing paraphernalia that we would find strange to look at. There were also helpful instructions on how to read a scroll, which also brought to mind just how cumbersome and time-consuming holding, rolling and unrolling one really is, and definitely spelled out to me just how much we should appreciate the invention of the book (or codex, as it was in antiquity)! Last but not least, “The Infinite Library” featured several beautiful frescos reminiscent of the famous ‘couple from Pompeii’, which depicted their subjects as both writers and readers, one of which showed a very lovely young lady reading what appeared to be a love letter. These gorgeous works of art give us a striking picture of how (wealthy) Romans wanted themselves to be seen – as literate and erudite. The fact that so many of these portraits exist is testament to just how highly literacy was prized in the ancient world.

A Roman writing tablet. Wax would be poured into the niches to serve as a writing surface, and would be replaced whenever it had been used up.

It is a shame that the exhibition is now closed, although English-speaking visitors might have found it difficult to access unless they, like myself, were heading to Rome on holiday. Nevertheless, I’d recommend a similar exhibition to anyone who’s interested in librarianship, particular ancient libraries and the history of documents. It would be lovely if the British Library could host a similar exhibition, as, in many ways, “The Infinite Library” was not just the story of books or art or culture, but the story of who we are.