Click here to book tickets for the conference and/or the concerts.

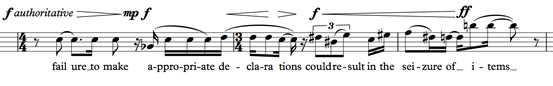

On Thursday January 19th and Friday January 20th, 2017, City, University of London is hosting a conference entitled Bright Futures, Dark Pasts: Michael Finnissy at 70. This will feature a range of scholarly papers on a variety of aspects of Finnissy’s work – including his use of musical objets trouvés, engagement with folk music, sexuality, the influence of cinema, relationship to other contemporary composers, issues of marginality, and his work in performance. There will be three concerts, featuring his complete works for two pianos and piano duet, played by the composer, Ian Pace, and Ben Smith; a range of solo, chamber and ensemble works; and a complete performance (from 14:00-21:00 on Friday 20th) of his epic piano cycle The History of Photography in Sound by Ian Pace. The concerts include the world premieres of Finnissy’s Zortziko (2009) for piano duet and Kleine Fjeldmelodie (2016-17) for solo piano, the UK premiere of Duet (1971-2013) and London premieres of Fem ukarakteristisek marsjer med tre tilføyde trioer (2008-9) for piano duet, Derde symfonische etude (2013) for two pianos, his voice/was then/here waiting (1996) for two pianos, and Eighteenth-Century Novels: Fanny Hill (2006) for two pianos. There will also be a rare chance to hear Finnissy’s Sardinian-inspired Anninnia (1981-2) for voice and piano, for the first time in several decades.

Keynote speakers will be Roddy Hawkins (University of Manchester), Gregory Woods (Nottingham Trent University, author of Homintern) and Ian Pace (City, University of London). The composer will be present for the whole event, and will perform and be interviewed by Christopher Fox (Brunel University) on his work and the History in particular.

The composer and photographer Patrícia Sucena de Almeida, who studied with Finnissy between 2000 and 2004, has created a photographic work, continuum simulacrum (2016-17) inspired by The History of Photography in Sound and particularly Chapter 6 (Seventeen Immortal Homosexual Poets). The series will be shown on screens in the department and samples of a book version will be available.

Patrícia Sucena de Almeida, from continuum simulacrum (2016-17).

The full programme can be viewed below. This conference also brings to a close Ian Pace’s eleven-concert series of the complete piano works of Finnissy.

A separate blog post will follow on The History of Photography in Sound.

Click here to book tickets for the conference and/or the concerts.

All events take place at the Department of Music, College Building, City, University of London, St John Street, London EC1V 4PB.

Thursday January 19th, 2017

09:00-09:30 Room AG09.

Registration and TEA/COFFEE.

09:30-10:00 Performance Space.

Introduction and tribute to Michael Finnissy by Ian Pace and Miguel Mera (Head of Department of Music, City, University of London).

10:00-12:00 Room AG09. Chair: Aaron Einbond.

Larry Goves (Royal Northern College of Music), ‘Michael Finnissy & Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: the composer as anthropologist’.

Maarten Beirens (Amsterdam University), ‘Questioning the foreign and the familiar: Interpreting Michael Finnissy’s use of traditional and non-Western sources’

Lauren Redhead (Canterbury Christ Church University), ‘The Medium is Now the Material: The “Folklore” of Chris Newman and Michael Finnissy’.

Followed by a roundtable discussion between the three speakers and composer and Finnissy student Claudia Molitor (City, University of London), chaired by Aaron Einbond.

12:00-13:00 Foyer, Performance Space.

LUNCH.

13:10–14:15 Performance Space.

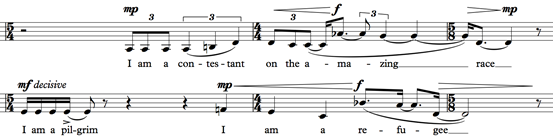

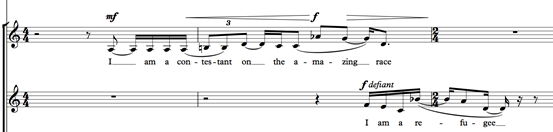

Concert 1: Michael Finnissy: The Piano Music (10). Michael Finnissy, Ian Pace and Ben Smith play Finnissy’s works for two pianos or four hands.

Michael Finnissy, Wild Flowers (1974) (IP/MF)

Michael Finnissy, Fem ukarakteristisek marsjer med tre tilføyde trioer (2008-9) (BS/IP) (London premiere)

Michael Finnissy, Derde symfonische etude (2013) (BS/IP) (London premiere)

Michael Finnissy, Deux jeunes se promènent à travers le ciel 1920 (2008) (IP/BS)

Michael Finnissy, his voice/was then/here waiting (1996) (IP/MF) (UK premiere)

Michael Finnissy, Eighteenth-Century Novels: Fanny Hill (2006) (IP/MF) (London premiere)

14:30-15:30 Room AG09. Chair: Lauren Redhead (Canterbury Christ Church University).Keynote: Roddy Hawkins (University of Manchester): ‘Articulating, Dwelling, Travelling: Michael Finnissy and Marginality’.

15:30-16:00 Foyer, Performance Space.

TEA/COFFEE.

16:00-17:00 Room AG09. Chair: Roddy Hawkins (University of Manchester).

Keynote: Ian Pace (City, University of London): ‘Michael Finnissy between Jean-Luc Godard and Dennis Potter: appropriation of techniques from cinema and TV’

17:00-18:00 Room AG09. Chair: Christopher Fox (Brunel University).

Roundtable on performing the music of Michael Finnissy. Participants: Neil Heyde (cellist), Ian Pace (pianist), Jonathan Powell (pianist), Christopher Redgate (oboist), Roger Redgate (conductor, violinist), Nancy Ruffer (flautist).

19:00 Performance Space.

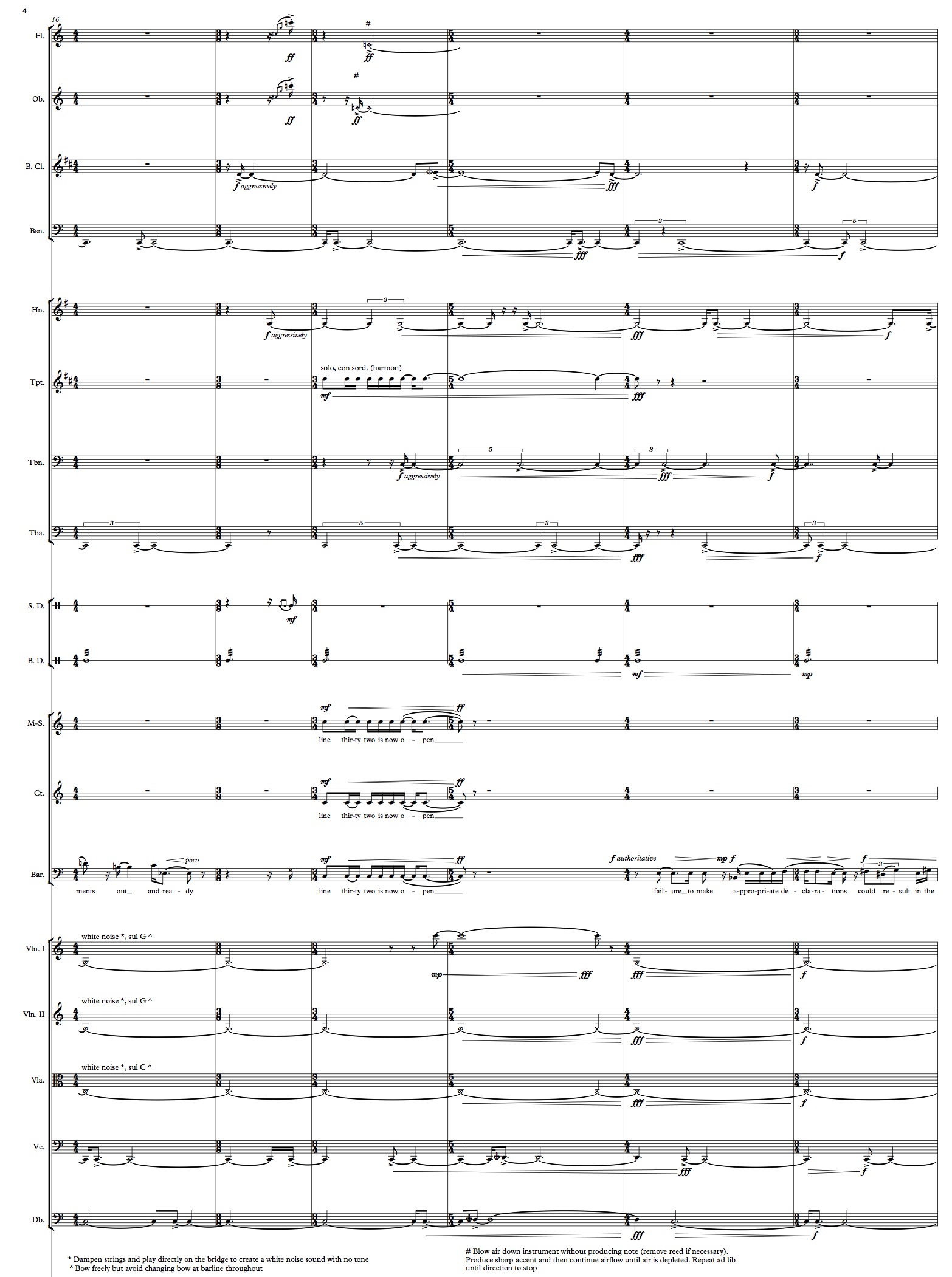

Concert 2: City University Experimental Ensemble (CUEE), directed Tullis Rennie. Christopher Redgate, oboe/oboe d’amore; Nancy Ruffer, flutes; Bernice Chitiul, voice; Alexander Benham, piano; Michael Finnissy, piano; Ian Pace, piano; Ben Smith; piano.

Michael Finnissy, Yso (2007) (CUEE)

Michael Finnissy, Stille Thränen (2009) (Ian Pace, Ben Smith)

Michael Finnissy, Runnin’ Wild (1978) (Christopher Redgate)

Michael Finnissy, Anninnia (1981-82) (Bernice Chitiul, Ian Pace)

Michael Finnissy, Ulpirra (1982-83) (Nancy Ruffer)

Michael Finnissy, Pavasiya (1979) (Christopher Redgate)

INTERVAL

‘Mini-Cabaret’: Michael Finnissy, piano

Chris Newman, AS YOU LIKE IT (1981)

Michael Finnissy, Kleine Fjeldmelodie (2016-17) (World première)

Andrew Toovey, Where are we in the world? (2014)

Laurence Crane, 20th CENTURY MUSIC (1999)

Matthew Lee Knowles, 6th Piece for Laurence Crane (2006)

Morgan Hayes, Flaking Yellow Stucco (1995-6)

Tom Wilson, UNTIL YOU KNOW (2017) (World première)

Howard Skempton, after-image 3 (1990)

Michael Finnissy, Zortziko (2009) (Ian Pace, Ben Smith) (World première)

Michael Finnissy, Duet (1971-2013) (Ben Smith, Ian Pace) (UK première)

Michael Finnissy, ‘They’re writing songs of love, but not for me’, from Gershwin Arrangements (1975-88) (Alexander Benham)

Michael Finnissy, APRÈS-MIDI DADA (2006) (CUEE)

21:30 Location to be confirmed

CONFERENCE DINNER

Friday January 20th, 2017

10:00-11:00 Room AG21.

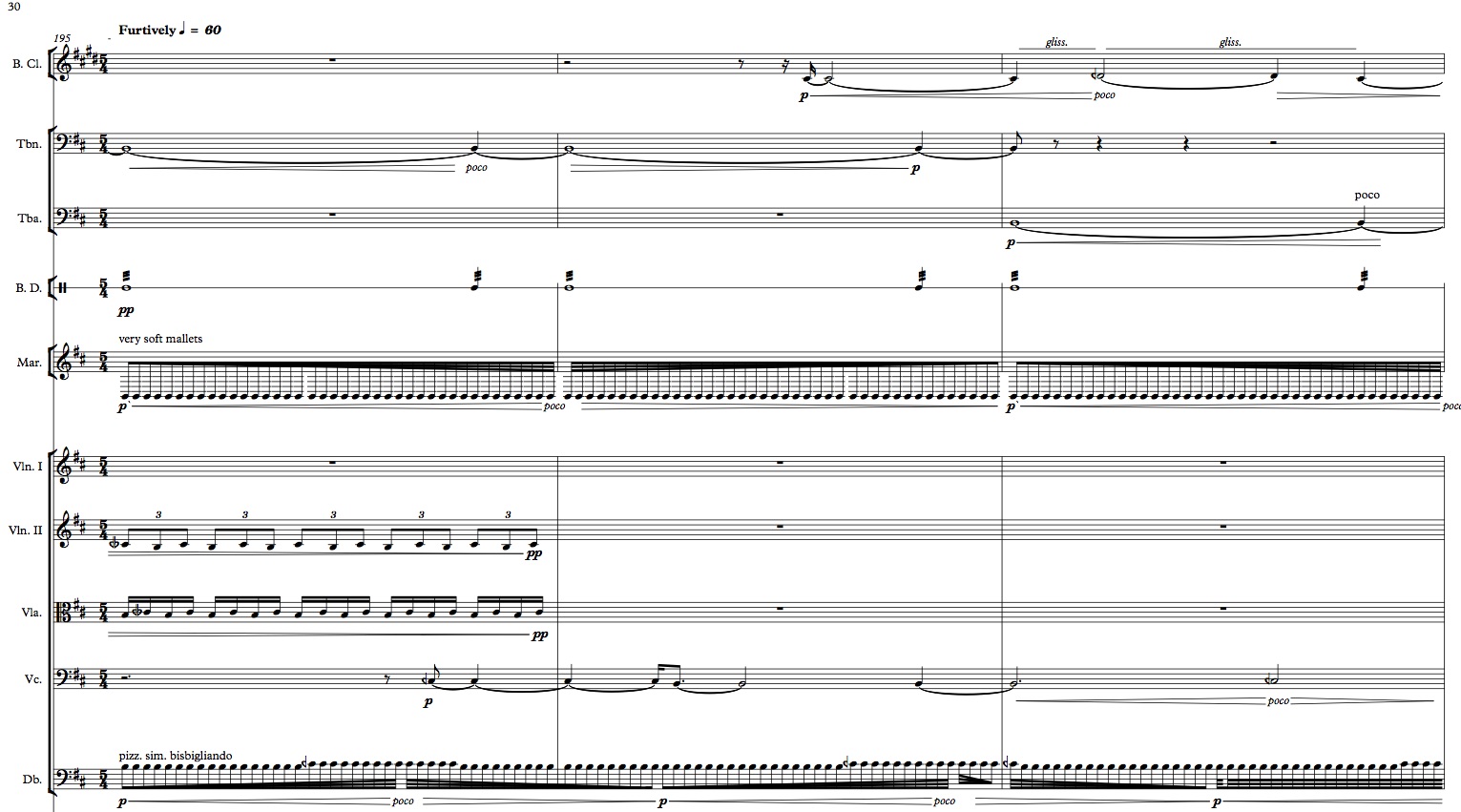

Christopher Fox in conversation with Michael Finnissy on The History of Photography in Sound.

11:00-11:30 Room AG21.

TEA/COFFEE.

11:30-12:30 Room AG21. Chair: Alexander Lingas (City, University of London).

Keynote: Gregory Woods (Nottingham Trent University): ‘My “personal themes”?!’: Finnissy’s Seventeen Homosexual Poets and the Material World’.

14:00-21:00 Performance Space.

Concert 3: Michael Finnissy: The Piano Music (11): The History of Photography in Sound (1995-2002). Ian Pace, piano

14:00 Chapters 1, 2: Le démon de l’analogie; Le réveil de l’intraitable realité.

15:00 INTERVAL

15:15 Chapters 3, 4: North American Spirituals; My parents’ generation thought War meant something

16:15 INTERVAL

16:35 Chapters 5, 6, 7: Alkan-Paganini; Seventeen Immortal Homosexual Poets; Eadweard Muybridge-Edvard Munch

17:50 INTERVAL (wine served)

18:10 Chapter 8: Kapitalistische Realisme (mit Sizilianische Männerakte und Bachsche Nachdichtungen)

19:20 INTERVAL (wine served)

19:35 Chapters 9, 10, 11: Wachtend op de volgende uitbarsting van repressie en censuur; Unsere Afrikareise; Etched Bright with Sunlight.

What characterizes the so-called advanced societies is that they today consume images and no longer, like those of the past, beliefs; they are therefore more liberal, less fanatical, but also more ‘false’ (less ‘authentic’) – something we translate, in ordinary consciousness, by the avowal of an impression of nauseated boredom, as if the universalized image were producing a world that is without difference (indifferent), from which can rise, here and there, only the cry of anarchisms, marginalisms, and individualisms: let us abolish the images, let us save immediate Desire (desire without mediation).

Mad or tame? Photography can be one or the other: tame if its realism remains relative, tempered by aesthetic or empirical habits (to leaf through a magazine at the hairdresser’s, the dentist’s); mad if this realism is absolute and, so to speak, original, obliging the loving and terrified consciousness to return to the very letter of Time: a strictly revulsive movement which reverses the course of the thing, and which I shall call, in conclusion, the photographic ecstasy.

Such are the two ways of the Photography. The choice is mine: to subject its spectacle to the civilized code of perfect illusions, or to confront in it the wakening of intractable reality.

Ce qui caractérise les sociétés dites avancées, c’est que ces sociétés consomment aujourd’hui des images, et non plus, comme celles d’autrefois, des croyances; elles sont donc plus libérales, moins fanataiques, mais aussi plus «fausses» (moins «authentiques») – chose que nous traduisons, dans la conscience courante, par l’aveu d’une impression d’ennui nauséeux, comme si l’image, s’universalisant, produisait un monde sans differences (indifferent), d’où ne peut alors surgir ici et là que le cri des anarchismes, marginalismes et individualismes : abolissons les images, sauvons le Désir immédiat (sans mediation).

Folle ou sage? La Photographie peut être l’un ou l’autre : sage si son réalisme reste relative, tempére par des habitudes esthétiques ou empiriques (feuilleter une revue chez le coiffeur, le dentist); folle, si ce réalisme est absolu, et, si l’on peut dire, original, faisant revenir à la conscience amoureuse et effrayée la letter même du Temps : movement proprement révulsif, qui retourne le cours de la chose, et que l’appellerai pour finir l’extase photographique.

Telles sont les deux voies de la Photographie. A moi de choisir, de soumettre son spectacle au code civilise des illusions parfaits, ou d’affronter en elle le réveil de l’intraitable réalité.

Roland Barthes, Le chambre claire/Camera Lucida.

Eadweard Muybridge – A. Throwing a Disk, B: Ascending a Step, C: Walking from Animal Locomotion (1885-1887).

Patrícia Sucena de Almeida, from continuum simulacrum (2016-17).

Click here to book tickets for the conference and/or the concerts.