James Saunders

James Saunders is a composer with an interest in modularity. He performs in the duo Parkinson Saunders, and with Apartment House. He is Head of the Centre for Musical Research at Bath Spa University. On Tuesday his music is featured in a portrait concert performed by our ensemble-in-residence, Plus-Minus, including a new work composed specifically for the event. We spent five minutes talking to James about his work.

Your works tend to explore open forms and processes. This brings with it the issues of generality and specificity, something that you have talked about previously. What is it about the boundaries between generality and specificity that draws you to compose in this field?

At the moment I see them as two states, and pieces I make tend to be broadly either specific or general. By specific, I mean that the score will indicate a more tightly controlled series of activities, normally with definite sounds of some kind or a clear temporal relationship, but still may be open in some way. The general pieces leave a lot of possibilities left open, and might be used to generate more specific pieces themselves. Recently this has become more of a focus for me. I tend to sketch out ideas for pieces in my notebook, some of which stay there for good reasons, but others are made quite quickly into scores, normally short verbal descriptions of processes. I’ve found over the past few months that they might also exist in a more specific state, taking the basic process and fleshing it out, giving it a context, normally with particular sounds. So as an example, I wrote a piece ‘things whole and not whole’ for Basel Sinfonietta in 2011 that models the way birds flock. The musicians are able to use any sound sources or instruments, as long as they can produce short sounds on cue. The new piece on bare trees in the concert on Tuesday is a version of this, but the players are given a series of pitches in short phrases. The cueing system is the same, but a different kind of patterning emerges, with each phrase coming to rest on a repeated unison pitch. I expect some of the other general pieces might develop in this way.

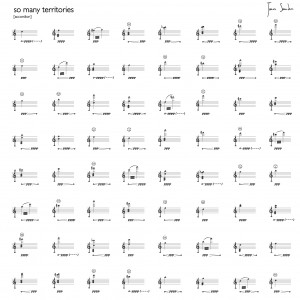

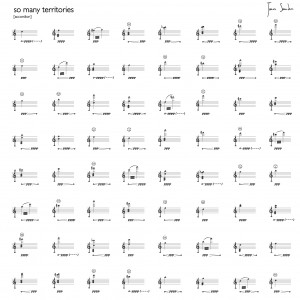

You have composed a new piece for Plus-Minus, being performed on Tuesday, in which you use a mutually orthogonal latin square to control various permutations of four parameters. Can you explain a little more about this compositional process and what we can expect of ‘so many territories’?

They’re a bit of a mouthful aren’t they? I first came across them in relation to George Perec’s ‘Life: A User’s Manual’, which is one of my favourite books and through which I developed a fascination with the Oulipo. Perec uses a Graeco-Latin Bi-square, which is a square gridded arrangement with each cell containing two elements, one from each of two sets. Across the square, each element of the two sets appears in each row and column only once, and each combination of the two elements occurs only once across the whole square. In the book, Perec uses this to determine the constraints for each chapter of the book, creating a set of permutations of elements from which to construct the narrative. It is possible to create squares with more than two sets, and they are mutually orthogonal if there is no repetition of the different combinations of elements across the square. In my piece, the score is presented as a 8×8 grid of cells. It took me a while to find four mutually orthogonal squares, but the result is that each cell contains a unique combination of four musical parameters (two pitches, a dynamic and articulation). In some parts this is rationalised a little where unplayable results occur, but it allowed me to define a space, both sonically and on the score. The players move across this grid independently, creating loops and chains of events as they progress.

Your recent works also employ musical cueing systems that explore group behaviour in your works. How does ‘so many territories’ fit within this context of cueing and group behaviour?

Your recent works also employ musical cueing systems that explore group behaviour in your works. How does ‘so many territories’ fit within this context of cueing and group behaviour?

There’s no cueing in ‘so many territories’ as such, but group behaviours may emerge. The players work independently across the grid, but stable states may sometimes develop where repetitions of cells in a fixed relationship occur. If this happens, players may either choose to submit and move on, co-exist for a time, or refuse to move on and wait for the other player(s) to submit. This determines the progression.

‘everybody do this’ was recently performed in Bath with four performers [watch here]. Next week we will see this performed with a larger group of around 20-25 performers. How do you expect the outcome to change considering the much larger ensemble?

Good question. It is likely to be a lot more chaotic of course. The piece works by each player giving spoken cues for actions to which the other players respond. Cues relate to pitches, noises, and devices, so for example if someone says ‘pitch 4’, then everybody plays their fourth pitch sound. The choice of sounds is left to the players to decide independently, so the combinations are determined through distributed decision making. All players give and receive cues simultaneously as they want. In the first performance it was possible for all of us to hear the instructions easily enough. Patterns were constructed and broken regularly, and there was a relatively high degree of order. With a much larger group it will be very different. It is likely that it will oscillate between having a few dominant voices to which everyone responds, smaller localised groups of concerted activity, and a few loners. To be honest, I can’t wait to find out. This piece is another group behaviour piece and is part of a series which explore organisation structures. So if this is a many-to-many relationship, the other pieces use one-to-one (‘what you must do, rather than must not do’, 2012), many-to-one (‘you say what to do’, 2014), and one-to-many (‘I say what to do’, 2014). These will all have been performed by the middle of the year, and the next stage of the project is to look at other more complex relationships. The master plan is to use these as modular blocks from which much larger networks can be built. They model organisation structures, and these tend to be complex, and often short circuit themselves at some point. Anyone who works in a big organisation will know what this feels like, so you might identify with the chaos which ensues in the piece, despite the occasional havens of order.

You can find out more about James Saunders and his work here: www.james-saunders.com

James’ works will be performed on Tuesday 8th Aril at 7pm in the Performance Space, College Building.

Admission is free. To book a place head to: http://www.city.ac.uk/events/2014/apr/james-saunders-and-plus-minus

Or follow us on facebook and twitter:

http://facebook.com/CityUniConcerts

http://twitter.com/CityUniConcerts