Dr Ernesto Priego, City, University of London

Ernesto Priego is a lecturer at the Centre for Human-Computer Interaction Design at City, University of London and the Editor of The Comics Grid: Journal of Comics Scholarship.

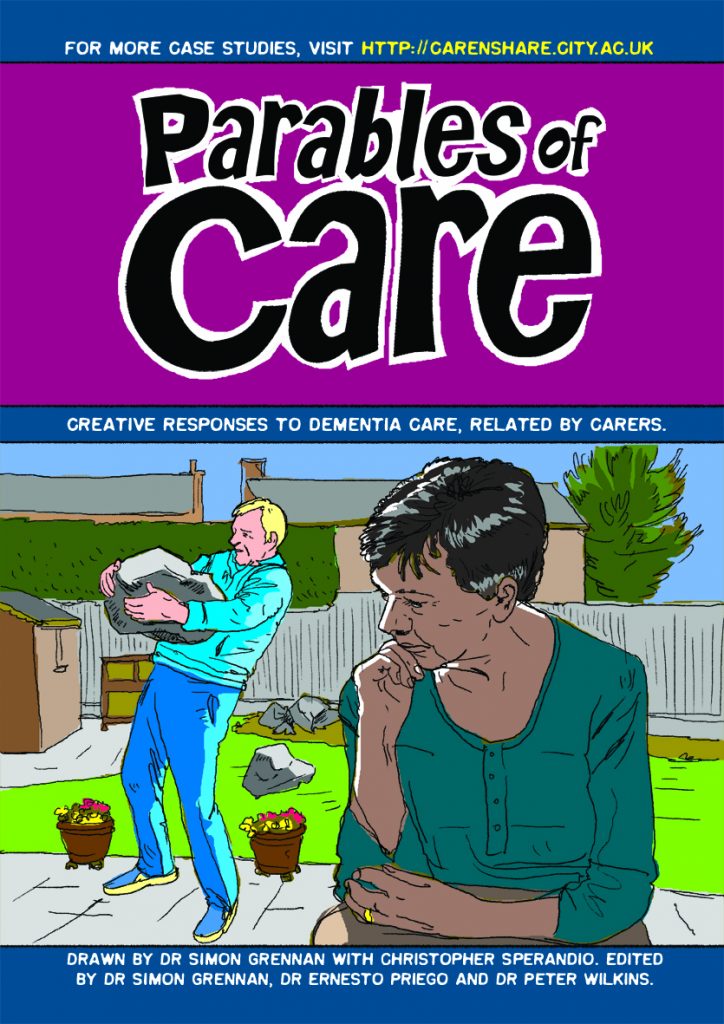

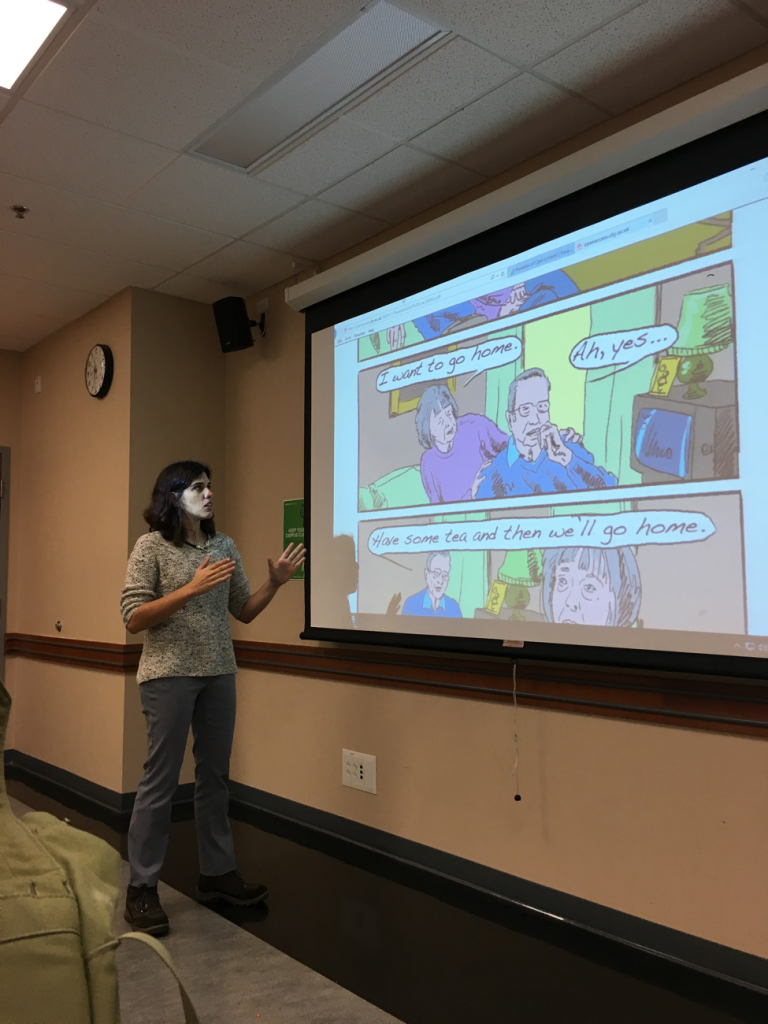

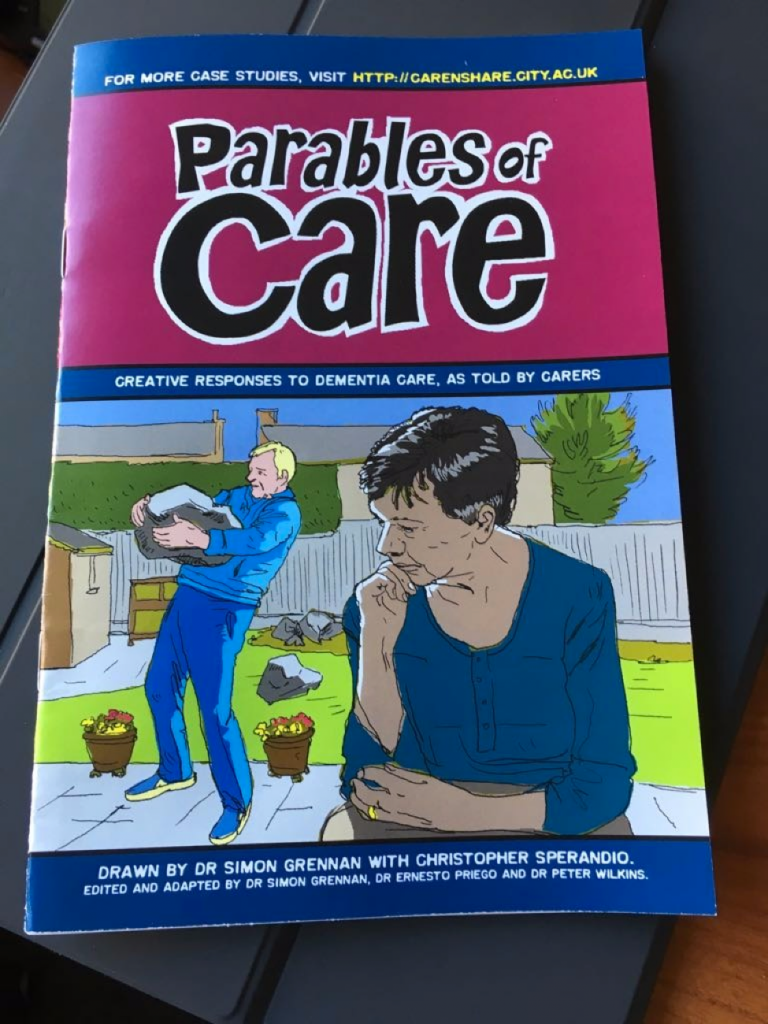

Ernesto worked in partnership with Dr Simon Grennan of the University of Chester, Dr Peter Wilkins of Douglas College, Vancouver, Canada, an NHS Trust, and colleages from HCID, leading the team to produce Parables of Care.

I asked Ernesto some questions about working on Parables of Care.

As a speech and language therapist researcher, I work with people who have aphasia and may have difficulty in reading large amounts of written text. People with dementia can experience similar challenges. What do you think the comics format offers that other mediums might not?

Ernesto Priego: My view is that comics are a unique medium because they often rely on a unique, complementary combination of writing, still graphic images and other components of visual communication. There are, of course, comics that are very wordy—they employ a lot (and I mean a lot) of written text. And there are, of course, comics that include almost no text at all (titles, indicia, series names are also written text). Unlike animation, video, TV or cinema, most comics, particularly printed ones, allow users / readers to linger on the comics page. Comics are therefore, in their own way, a very ‘mindful’ medium, as they often rely on a type of hyper awareness of concrete and abstract constraints, of context.

In most comics, time passes through different vehicles so to speak: through the time of the written text, the time represented through layout (panel size and arrangement and the placement of characters, backgrounds, props, narrative components), the time represented through panels in sequence and the gap between them, and the time it takes each reader to read or navigate the comic itself. So comics are a very complex medium indeed, but at the same time they give users a freedom to linger and to interpret information in a way that synchronic media such as music, video, TV or film do not allow them to.

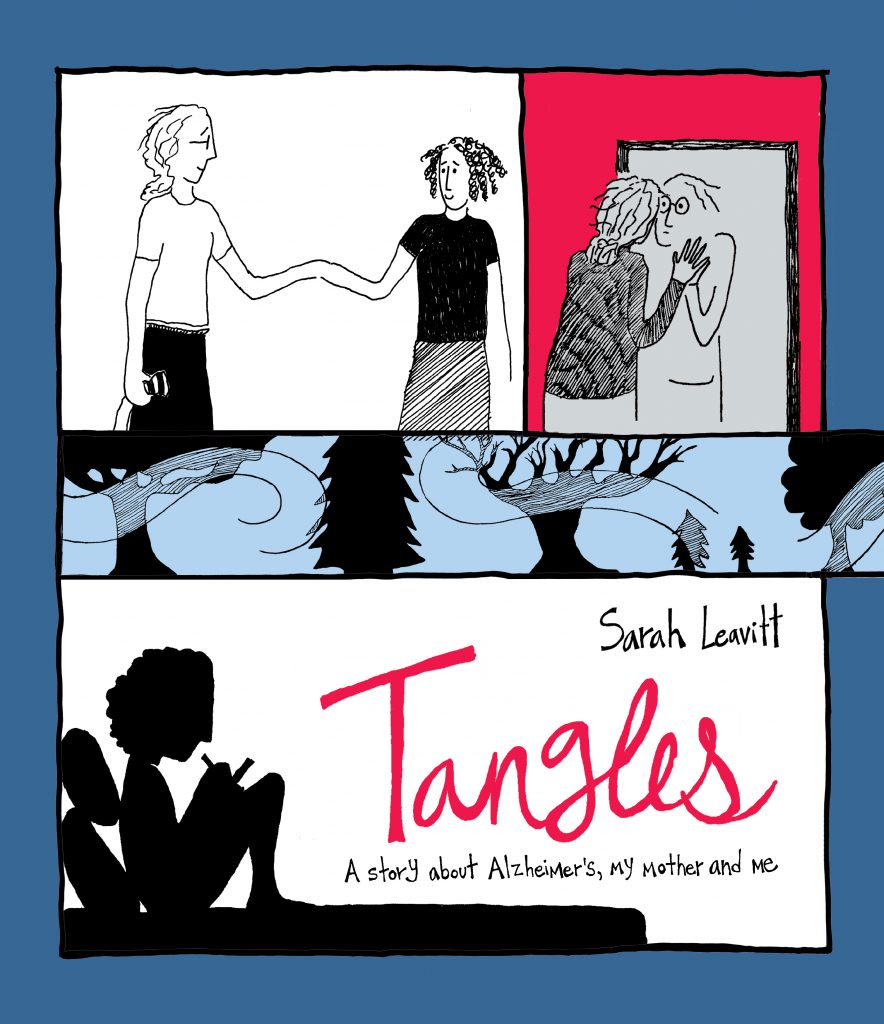

Rather than just a question of comics being able to present ideas without the need for many words, in this case we think of comics as a medium that can actually evoke the kind of de-structured and re-structured experience of time that is akin to dementia but also to illness, ageing and caring in general (Paco Roca’s Wrinkles does this very well).

Illustration from Wrinkles, a graphic novel by Paco Roca. © Knockabout Comics, 2015

In many cases, people with dementia, as well as their carers, experience a time which is ‘out of joint’ (Hamlet, that tragic hero…). The fragmentary yet sequential structure of the comics in Parables of Care seeks to communicate and empathise with this experience, and in this way it attempts to share a way of experiencing the world.

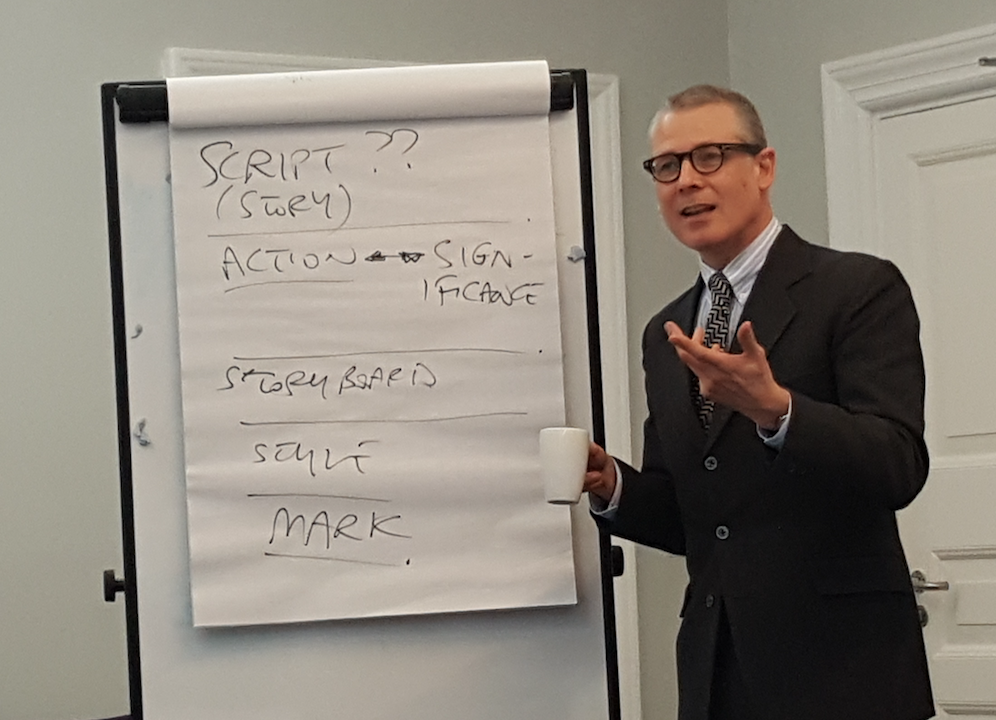

I’m more familiar with comics being used to tell stories of superheroes. How are Care’N’Share stories similar and/or different to these more traditional comics narratives?

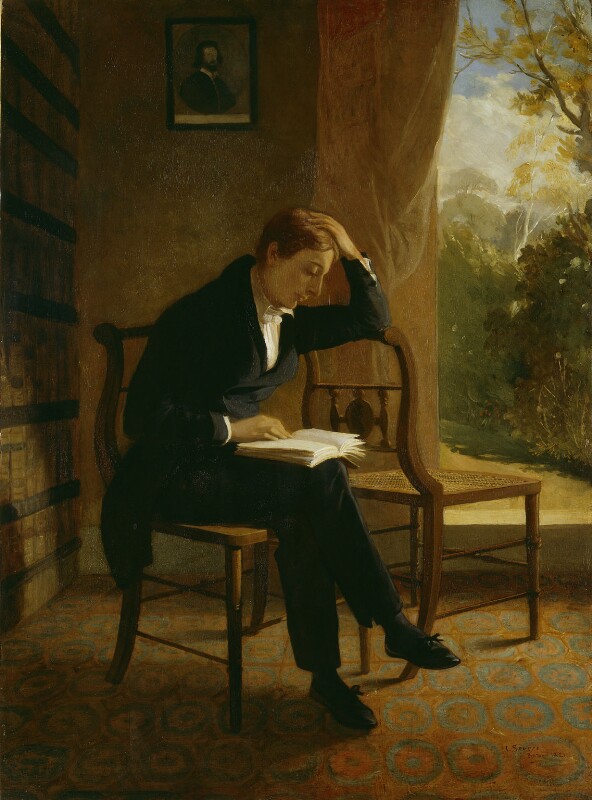

EP: That’s a very good question. For many people the term ‘comics’ means ‘superheroes’. Comics are much more than superheroes but in the case of the Care’N’Share stories the analogy achieves the status of poetic justice. Peter said in the previous Q&A that the Care’N’Share caregiver-storytellers are poets. This is true. Your question makes me think that they are similar to Romantic poets, and in this sense to heroes. Caregiving is heroic because it is a journey, and the hero’s journey is both motivated and defined by a sense of ethics, a thirst for justice and order, and fate or destiny. I also think people with dementia are poets: they see the world in a way that forces the carer and other people to realign their way of seeing things. Like the poet, they often see things that others don’t. The carer is a poet-hero because they need to learn to interpret that poetry and engage in creative endeavour themselves.

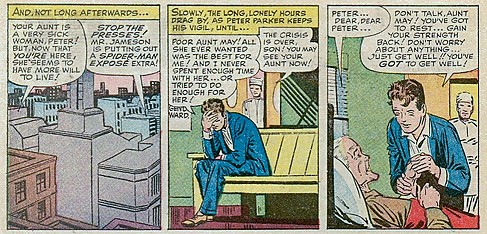

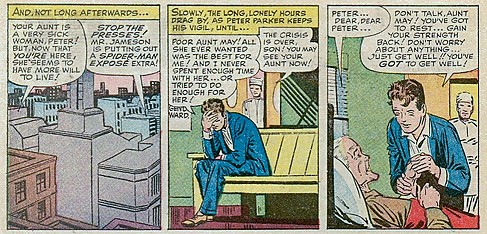

The best superhero comics, in my mind, are not about invincible heroes but about vulnerable folk that are somewhat different: their ‘superpowers’ lie in their difference and in their ability to find solutions to problems for the betterment of their communities. (Think of Peter Parker, for example). There is a lot of doubt, anxiety and pain in the hero’s journey.

Peter Parker cares for his aunt May after she suffers a heart attack. In Stan Lee (writer), Steve Ditko (artist), Sam Rosen (letterer), The Amazing Spider-Man, Vol 1, No. 17, October 1964. © Marvel Comics

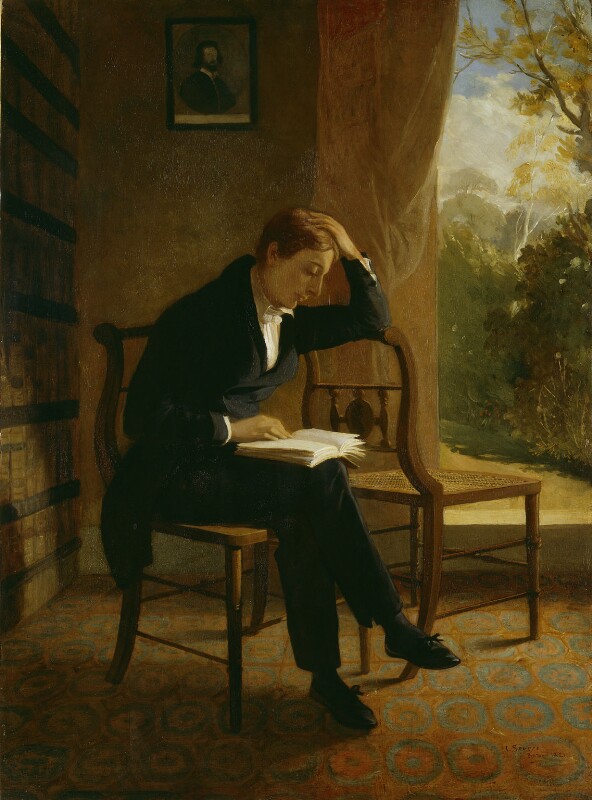

John Keats, by Joseph Severn, 1821-1823 – NPG 58 – © National Portrait Gallery, London

The caregiver-storytellers of Care’N’Share however do not see themselves as heroes, but what they do is heroic, it requires a sacrifice and a determination that is only possible when our deepest fears are defeated and our inner super powers come to the fore. I have the uttermost respect for dementia carers/caregivers. The stories they share are lessons to us all on our duty to our fellow human beings on how to empathise with what is often completely incomprehensible and find solutions that are respectful, loving and fair.

So it’s important to say that to me the beauty of ‘Graphic Medicine’ is that it’s not about idealisation or about fitting into generic narrative structures and archetypes. It’s about the personal journey, the vulnerabilities that make us human, and discovering the ways in which we can overcome serious challenges.

What have you learnt about dementia through your experience in creating Parables of Care?

EP: I am still learning a lot. The statistics alone provide sufficient evidence that dementia is one of the key public health and social challenges of today, not just in the UK but around the world. Working in this project required having an open mind about what we could achieve and be willing to accept that our contribution would be relativelly small but potentially impactful on some level.

To come back to my previous answer I think all of us working in the project learnt that a lot is achievable in terms of health care of incurable conditions if there is tolerance, empathy, creativity and imagination. In general working in adapting the stories forced us to attempt walking in the carers’ shoes. Susan Sontag wrote a beautiful book discussing the im-possibility of experiencing the pain of others through photography. I hope Parables of Care can contribute to share the experience of dementia care in a respectful and sensitive way.

Where else might comics be applied in healthcare? Where do you want to go next?

EP: Ah, that is the question! Short answer: almost everywhere. We believe that comics can be brilliant health information resources. And I think that Health Informatics and Graphic Medicine are a match made in heaven. We are already working on that next step. I am definitely interested in developing more work that explicitly connects the dots between graphic narrative and User-Centred Design and Interaction Design. I won’t say more for the time being. Watch this space!

–

Dr Abi Roper is a Research Fellow at City, University of London. She is a speech and language therapist and researcher passionate about technology use within atypical speech & language populations.

–

Parables of Care can be downloaded as a PDF file, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, from City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/18245/.

If you live in the UK you can request printed copies at no cost here.