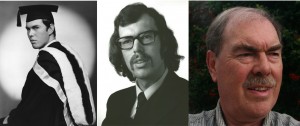

Richard Storey studied MBA Administrative Sciences (then known as an MSc) in the second ever intake, graduating in 1969 from what was then the City University Business School (CUBS). He’s recently retired. We caught up with him for our continuing #Cassat50 series.

Richard Storey studied MBA Administrative Sciences (then known as an MSc) in the second ever intake, graduating in 1969 from what was then the City University Business School (CUBS). He’s recently retired. We caught up with him for our continuing #Cassat50 series.

Why did you come to Cass?

I was only 22 and had just been working for one year in the insurance industry before I started my MSc in Administrative Sciences, as it was then.

I graduated with an Economics Hons degree from Sheffield and had plans for a career in sales but I couldn’t get a job on the career ladder. I asked my tutor at Sheffield what should I do and he said, “why not do an [MBA]? “What’s that?” I said, and he told me it’s an up-and-coming extra qualification and it should set you up for a good career. So that was the first reason.

The second reason was, because I had only been working for one year, I couldn’t afford to go away to study. My parents lived in Surrey and put me up for the year – so the mum and dad factor was important! Luckily, in those days, I was able to get a grant to cover my fees!

I chose Cass specifically because I was quite young and the course itself was in its infancy. I looked at the profile of the lecturers and they had a good balance of skills and business experience. The course not only gave me a broad postgraduate business training but also offered the opportunity to gain and develop my marketing skills.

What was your experience of studying at Cass?

Well, I loved it! I found it very interesting. It was a challenging course and unlike my undergraduate experience of university because it was a twelve month course. We worked five days a week for about 40 weeks and then the final 3 months were devoted to our thesis. This was definitely quite different from my three years at uni where I did rather less studying. Looking back now I realise just how little work I did in my middle year! In my first year I did work quite hard, but then not much real work until the third year! That was being a typical undergraduate in the 1960s!

As far as I was concerned the CUBS staff were very knowledgeable, good and engaging teachers whose teaching was insightful and they encouraged debate. Around 30 years later, when I visited the business school for the first time in 25 years, there were over 300 full-time MBA students enrolled on the course – quite a change from my year which was only the second full year of the course when there were 45 of us. In the first year there were only 17. Those were the really early days!

It was great to be part of a small MBA cohort – I was part of new, very select group. We really benefitted from closer tutoring in small groups. We all came from very different backgrounds, including chemical and mechanical engineering, finance, economics, and some who had done languages. It was a very diverse group and we were all coming to learn how to manage businesses. We learned a lot from each other and through shared experiences. I did enjoy it, it was a real eye-opener and I had a great time!

The course must have been very different then! What did you learn about?

We had a great economics lecturer, Douglas Vaughan, whilst an entertaining lecturer, Oliver Vesy-Holt, led the marketing team. Sid Kessler took us for industrial relations whilst Allan Williams (the author of an interesting book on the business school’s history – The Rise of Cass Business School) covered occupational psychology. We also had a French lady, Suzanne Colvington, who taught us commercial French! I imagine it is so different these days. Quite a lot of us were thinking of careers in industry rather than finance because in the late 60s more than 25% of UK GDP came from manufacturing (today it’s less than 11%).

One specific thing I remember us doing was a novel simulation business game. Computing was in its very early days in 1968 and we played a business modelling game in which we competed in teams of about six. We used a prediction model to see who came out with best choices. As a team, we made specific decisions each week after which our choices were sent to be computed at the IBM mainframe computer centre. A week later the results would come back with decision outcomes. We then had to look through what seemed to be endless pages of dot-matrix print outs to see how we had performed and the impact on sales revenues, margins and bottom line. We would discuss tactics, send our decisions off again and wait another week. The games would take six or more weeks to complete! Clearly computers were new and very basic so offered little in the way of detailed analysis but we were fascinated by this rudimentary IT which certainly had impact – and we could compare the effects of our decisions with the other groups.

Overall, it was quite different from my undergraduate training providing, as it did, more thinking time, problem solving and experience in team working.

What’s your favourite memory?

I think fondly of my great relationship with the staff and tutors, and the access we had to visiting academics and business people through visiting lecturers. Wine and cheese parties (credit to the first year business students from 1967-8 who started the idea) subsidised by the business school were de rigueur, and speakers were invited by the postgraduate study body for the MSc group. On one occasion we invited Enoch Powell and he came! In those days business schools were rare and I imagine it was an interesting experience for them, too.

I certainly built lifelong friendships with some of the people who did course with me. Because most of us were so young, we really developed the social side together. Most of us had only one or two years of work experience before starting so we were in our early to mid-20s. We had discos on the Thames every now and then and an annual dinner. Before we graduated we formed the Gresham Grasshoppers to be the CUBS alumni, the first ever alumni association of the Business School which went on to hold annual dinners in the City and occasional other social gatherings.

For me, doing the course involved a daily commute from New Malden by train into London and then by the Waterloo & City Line to Bank Station and short walk to the original Gresham College in Basinghall Street. The dress code was far removed from our undergrad days so there I was wearing a shirt and tie sitting on trains alongside city men in bowler hats with rolled up umbrellas!

Are you in touch with the Gresham Grasshoppers still?

I’ve not been in touch with any of them for a while but I’ve got email addresses for two or three of them! One of my Grasshopper friends, Steven, married soon after graduating and I was asked to be godparent of his first child, who was actually named Richard after me! It was easy to keep in touch throughout the 1970s when we were all still working in and around London but since then it’s been harder. It’s been quite some years since we met. Tony, Andrew, Chester and Ronald – I can remember your names but where are you now?

How did studying at Cass change your life?

First of all, when I came to Cass I had an economics degree but a job I didn’t like! I was made rapidly more employable and got a job in the paper industry in Kent when I was still doing my thesis. I got in touch with my new boss and he agreed I could did my thesis around the paper industry, which I really enjoyed. It was relevant to them and they benefited from my market research, which got published in both Packaging and Converter magazines in 1970.

Secondly, the management skills I learned became increasingly useful as my career developed. They really came into their own when I reached middle and senior management. Back then I was quite young and inexperienced and started right at the bottom as an assistant to the advertising manager and spent most of my time proof reading brochures and handling print work through a print company in the east end of London. So, I didn’t use my MBA for several years but once I got a little way up the ladder my training started to kick in. I imagine today MBA students would be expected to have more work experience than I had! I may have gained more if I’d done the MBA course later, but that’s not how it worked 50 years ago. Also, I’ve found that the older you get the harder it is to commit to the regime of learning.

Having an MBA helped me earn respect from my managers and peers as my career developed. In terms of marketing, I became a senior marketer but then was able to switch and establish myself in general management. I think this would have been much less likely without my MBA. I probably could have got to be a senior marketer but maybe not beyond. I spent 12 years in marketing and then a further 10 years of general management before I started my own business, and I think my MBA helped me make a success of it.

In the early years after leaving the Business School, access to the wise counsel of past tutors was really helpful in my early career development. It was great to be able to go back and know you had an open door to talk to them. One person I am still in touch with is one of my tutors! Axel Johne, another marketing lecturer and now Professor Emeritus at Cass, was only a few years older than us so we shared a similar outlook on life. With his wife, Sue, he came to visit us in North Somerset last summer!

I also think that having an MBA, in which I had majored in industrial and international marketing, helped me to gain full membership of CIM (Chartered Institute of Marketing) without taking the formal exams. I think I satisfied the requirements by doing the MBA and I went on to become a fellow of the institute. I don’t think it would work today, though, as there are special senior management routes to entry.

Throughout my life my MBA skills have been like a toolbox which I have carried around with me and opened up from time to time when I’ve been faced with unfamiliar challenges.

Have you had a career highlight?

In the 60s Philip Kotler was, and arguably still is, a world leading marketing guru and his book, Marketing Management, is one of marketing’s bibles. It had a big influence on me during my time at Cass and during my subsequent career development. Kotler is now in his 80s and based in Chicago. Imagine my delight at being asked to join a transatlantic video link with him, organised by the Levitt Group, a London-based group of senior marketers of which I am a member.

So, in autumn 2015 at a meeting hosted by the Royal Society of Medicine in London, the link was set up to enable him make a presentation to our members. The audience with him was, in part, to allow him to promote his latest book, Confronting Capitalism, which was the subject of his talk and which examined how marketing today influences consumer behaviour. We had been invited to text in any questions we wanted to put to Kotler after his talk. When it came to question time, mine was the first! “Good Evening Richard!” he said. I said “My question is … there is evidence that marketing is losing its influence at the top of business. Of all the companies in the FTSE 100, in 2013 when the most recent analysis was done, only 8% of all chief executives had a marketing background (by comparison, 52% have come up through finance functions). This was down from 11% in 2008 and has been declining for over 20 years. How are marketers going to regain their influence at the top table?” He replied succinctly: “Finance. Marketers must have a better understanding of finance”. It was definitely a career highlight to speak to one of the most celebrated gurus of our profession!

If I may, I’d like to add a personal footnote to this experience. Grumpy old man I might be, but in my view marketing has today largely lost its strategic position as a core business discipline and, as a result, lost its influence in the boardroom. The coming of the digital age has seen many practitioners view marketing as a communications tool rather than as a key element within business planning and strategic business development. Many younger marketers I meet today don’t seem to share the same ambition we had of using our marketing skills to drive our careers to top management. Rather, they seem to be developing careers in the type of marketing activities which are not seen as strategic – much of it focused on digital marketing communications. Being at the centre of new product and service development, having a major influence over pricing strategy and embracing sales as part of the overall marketing function, all key elements of marketing, all too often seem to have been relinquished to other functions. It is not surprising, therefore, that fewer and fewer marketers fail to achieve the top jobs at the height of their careers.