Guest Editorial By Lindsay Palmer

When foreign correspondents began flooding into Greece to cover the influx of refugees arriving there from Turkey, local journalist Irene Lioumi saw the potential for a new career path. Lioumi had twenty years of experience covering the news. But one day, she got a phone call from a Turkish photographer.

“She wanted to come here and take some shots, and you know, in Idomeni, it’s very close to the Greek and the Macedonian borders. And there were so many refugees there, trapped, because the borders were closed. So all the foreign journalists wanted to go there and make some documentaries or films, and that’s when she called me, and asked me if I could help her, if I could find the car, if I could do the job.”

The photographer from Turkey was looking for a “fixer”—a locally-based guide hired to help foreign correspondents translate unknown languages, navigate unfamiliar geographies, and connect with people from different cultures. Though Lioumi could just as easily cover this story on her own, she decided to take the photographer’s offer. “We don’t have jobs here in Greece, because of the economic crisis. So it was an opportunity for me, and I grabbed it,” Lioumi says.

Lioumi is one of thousands—perhaps, millions—of news “fixers” collaborating with foreign correspondents around the world. Media workers like Lioumi do everything from arranging travel, to facilitating interviews with sources, to advising correspondents on how to stay safe in the field. While it might be easy to conceptualize this work as merely “logistical,” there is much more to news fixers’ labor than logistics.

More Than A ‘Fixer’

For my recent book on the stories that news fixers tell about their work, I talked to 75 fixers from 39 different countries. I learned that some of these media collaborators prefer to be called “local producers,” rather than “fixers,” because they feel that the term “fixer” implies an unskilled laborer. Other people who spoke with me said that they like the term “fixer” because of its international recognizability and because it implies resourcefulness.

Most of their stories had one thing in common, though. The vast majority of the people with whom I spoke suggested that their work is creative in nature, and that it requires a high level of skill. This is because news fixers are constantly performing—they are perpetually emphasizing different aspects of cultural identity in order to act as mediators between their foreign clients and the people in the field. On the one hand, they have a “local” connection. Even if they are not originally from the places where they work, they have a certain level of regionally-specific knowledge that they are expected to use to the foreign correspondent’s advantage.

For instance, though Lioumi is not a refugee herself, she has spent so much time helping foreign journalists cover the people in the Greek refugee camps that she has become the “go-to” person on the topic. But this “expert” status comes as a result of being connected at a local level.

“You need to have connections, need to know deeply the local system,” says Lioumi. “How the local system works, you know, the ministries, the local authorities, hotels, drivers, translators, restaurants, everything. Of course to have basic knowledge, more than basic, of languages.”

Local Knowledge

On another level, news fixers have to know how to think outside of their own “local” experiences and imagine an audience for the news story that might see the world through different eyes.

“You don’t know how much they know about their people and how much their people know about your land and what’s happening in your land,” says Lamprini Thoma, another journalist who also works as a fixer in Greece. “Sometimes we forget that we are not doing this story for Greeks, we are not doing this story for us, we are helping someone else to get his story, it’s not our story.”

Whether they see it as their story or not, news fixers are also constantly working to help the correspondents conceptualize what the story actually is. And although most foreign correspondents couldn’t cover their stories without the help of their local collaborators, these important media workers are virtually unknown to news audiences. They also never know whether they’ll be treated like collaborators at all.

“I had a client, I will not name him, from the BBC, who paid me (and I have a very big fee by Greek standards) to hold his eyeglasses,” says Thoma. “And he actually didn’t want me to make any suggestions. And when I tried to talk to him, he was like, ‘Do your job, be there, and if I want anything, I will tell you.””

Some of Thoma’s other clients struggled to understand why she couldn’t secure them a four or five-star hotel near the refugee camps.

“There on the border, there are no three-star hotels, there are no two-star hotels, there are just rooms. You cannot have it, so it’s not my fault, I cannot build it, you know,” says Thoma.

Journalism Needs More Fixers

Incidents like these point to the need for more journalists (and journalism scholars) to engage with news fixers’ unique perspectives on the work that they do. While virtually all the people I interviewed asserted that they have worked with wonderful correspondents at different points in time, there were also several stories that echoed Thoma’s.

News fixers are not local logisticians or “support” staff. Neither are they the journalists’ “assistants” or travel agents. They are local collaborators. Whether they identify as experienced journalists in their own right, or they embrace the title of “fixer” as a career path in of itself, these media employees are vital to the work of international reporting. The world’s human rights violations simply could not be covered without the creativity and skill of the people who hold the international news industries on their backs.

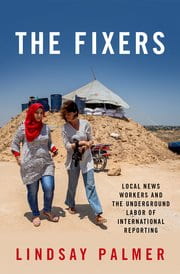

Find The Fixers by Lindsay Palmer, Oxford University Press, here.