[Provisional draft notes shared as a prompt for future research group discussion]

My interest in the sociology of texts, transmedia storytelling and the role of materiality in the reading/collecting/reception/user experience, particularly in the case of comic book cultures, originally found a welcoming conceptual framework within the digital humanities. Recently, my interest has been evolving towards exploring the role of media archaeology within human-computer interaction design.

Media archaeology, as discussed by Jussi Parikka (2011), is a branch of media history that studies contemporary media culture by looking into past (also called “residual”) media technologies and practices. Media archaeology takes a special interest in practices, devices and inventions that may be now otherwise forgotten. It addresses the rapid obsolescence of software and hardware, and poses that their collection, preservation, conservation and study can provide important context for multidisciplinary analysis and innovation.

In particular, I have been recently drafting arguments and potential methodological and domain approaches to critical narrative design and speculative design (sometimes also called “design fiction”, though both terms are not always used to mean the same thing). Needless to say, all these terms have specific meanings and require further clarification and discussion, even for the initiated, let alone those new to them. For an intro into the relationships between the terms “critical design” and “speculative design”, I recommend Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby’s books, Design Noir: The Secret Life of Electronic Objects (2001) and Speculative Everything: Design, Fiction, and Social Dreaming (2013).

According to Henry Jenkins (2007), “transmedia storytelling represents a process where integral elements of a fiction get dispersed systematically across multiple delivery channels for the purpose of creating a unified and coordinated entertainment experience. Ideally, each medium makes it own unique contribution to the unfolding of the story.” Transmedia is a mainstream term within contemporary literary and cultural studies, but its application and study goes beyond the mainstream humanities. Interaction designers are well aware that humans “are increasingly living their lives […] in multisensory, narrative driven ways” (Spaulding and Faste 2013).

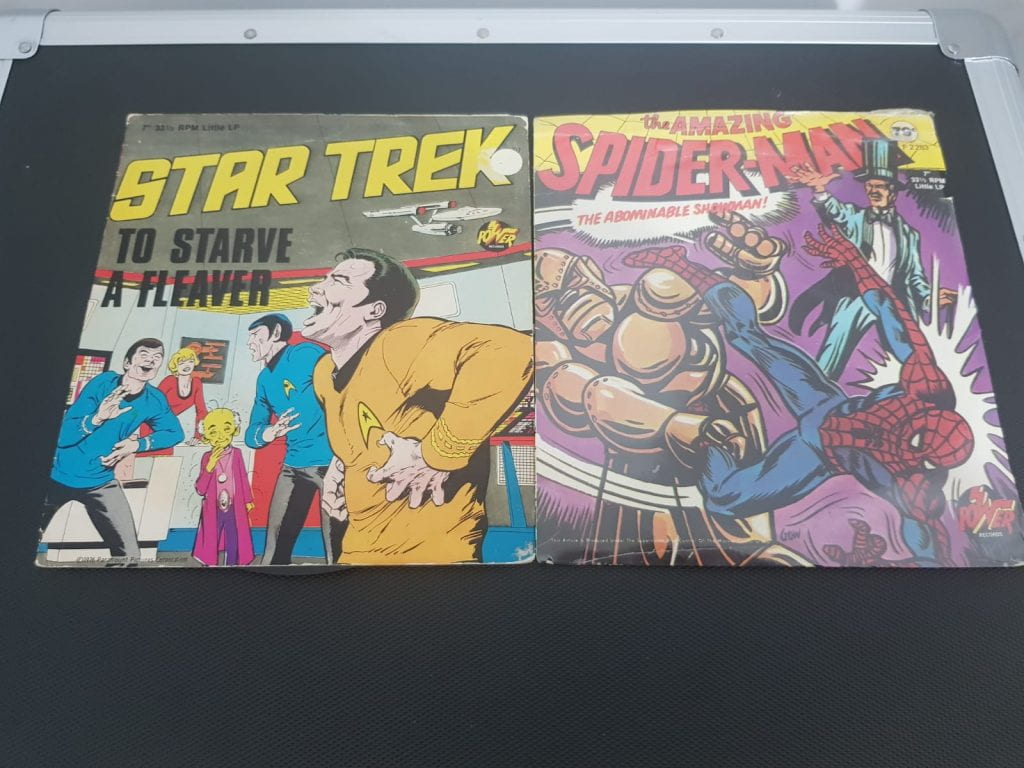

I took the photos above of two items in my record collection. They are two 7″ vinyl records containing the audio recordings of two stories based on characters, situations and fictional worlds at the time (late 1970s) mostly developed through comic books (today it would probably be film, rather than comics). I played them the other day and I was once again amazed at how immersive and engaging (in spite of some unavoidable and fully expected silliness that hasn’t aged well). As storytelling, both recordings qualify as fully immersive devices that expand fictional universes beyond their original media and that stimulate the imagination via different senses in a media-specific way. (For more context on these records and the label that released them, see Ettelson 2015).

This brief note is meant to share my interest in continuing exploring how media archaeology approaches to examples like these audio comic books in 7″ vinyl, can help us understand better how “residual media” could offer valuable context into the affordances of transmedia in both a pre-digital and in a fully networked, digital, cloud-based eras. This implies that “transmedia” is (of course) not only a 21st century phenomenon.

Within the field of HCI it is now well known that storytelling is a critical design tool in human-computer interaction, in particular by addressing how an exploration of potential futures can inform strategies around the problems of the present (see for example Dow et al 2006). How do form and content, materiality and information, inter-relate to participate in the user experience? Storytelling can also be a powerful strategy to understand the designs of the past, and to understand how these designs always-already include future designs- what can we learn from the design of things past, what stories do these objects tell, and what kind of insights can we obtain from them to design the present and the future?

Hoping these brief notes help as a starting point for further discussions between members of this research group.

One Comment