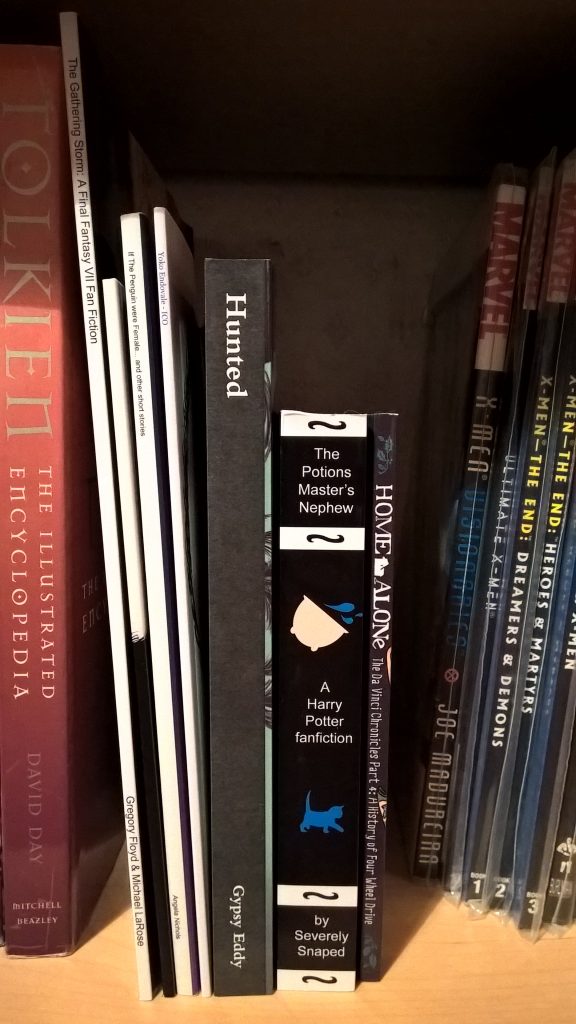

I recently decided to start a collection of fanfiction books.

This may seem like a bit of an oxymoron, especially nowadays when most fanfic is published online and most fans aren’t even aware it exists in book form. When you say ‘print fanfic’, most people think you mean fanzines. But I’m talking about books, actual fanfic printed in book format. I can’t say exactly what spurred on my sudden decision to collect fanfic books, especially when a good portion of its contents already exist online, and free. Maybe it’s just the bibliophile in me. Maybe it’s just the librarian in me. Maybe it’s just the collector in me. Maybe it’s just the fan. Most likely it’s all of the above.

I was first introduced to the idea of fanfic in book form in the mid-2000’s when my sister’s friend sent her a beautiful illustrated book of her fanfic (which I briefly mentioned a long time ago in a previous blog post). It looked so gorgeous, so professional, that the concept stuck in my mind, and a few years later I published my own fic in book form. This was more for my own benefit than anyone else’s. I just really wanted to hold my own words in my hands, to leaf through them, to annotate them, to put them on my book shelves just like the other treasured tomes I possess. It turned out that there were a small number of fans who also wanted copies, and so I opened up access to the books on Lulu.com

It wasn’t until I started research on my Ph.D. that I discovered that the fanfiction book was more common than I first thought it was. I was doing a random search for my ship on Amazon when I discovered a certain book that I may also have mentioned in a previous blog post. I bought a copy (for research purposes initially), mainly because I was intrigued that this book of fanfic was being sold (presumably for money) on a major online bookstore, and had an ISBN (Lulu.com will make these books available at major bricks-and-mortar bookstores, such as Borders, in this case). I haven’t linked to this particular book, since I don’t want to risk drawing the attention of rights-holders to the author, due to the work’s legally grey area.

At the Fan Studies Network Conference last year, I was shown some gorgeous fanfic books, also printed by Lulu, by an acquaintance, and this again reminded me that ‘this was a thing’. At this point, I actually did a little bit of digging into the phenomena and discovered the notorious case of Lori Jareo’s Another Hope, a Star Wars fanfic book that was sold in major bookstores, and was finally shut down by Lucasfilm in 2006. At the time, it caused significant ripples in the fan community, who were afraid that the furore would cause a backlash from the Powers That Be against fanfic itself. Taking a look around the net, I was able to find that there was quite a sizeable amount of fanfic books out there, and since this seems to be a little-known area of fandom (and fandom research), I thought I would start up a collection of my own – for both research and entertainment purposes.

From a research perspective, there are three strands to my interest in collection fanfic books. The first centres around changing modes of publication. In the digital era, print-on-demand (POD) has meant that self-publishing has become an affordable reality for many, and there is no longer the stigma of publishing through a ‘vanity press’. This suggests that the internet has afforded yet more ways for fans to publish their work, apart from digital or amateur press avenues.

The second area of interest revolves around the materiality of the book, and the fact that some fans still like to have their work presented in a physical format; and that others still like to buy physical written works, despite the free/gift culture that exists within the fan community. I suspect that this may have something to do with idea of collectability – that there exists in the fan the desire to possess physical tokens of their fandom, the collective size of which may bestow fan capital. This interest in owning physical works is especially interesting considering the recent decline in e-book sales. Could the phenomenon of fanfic books tell us something about why print books sales are once more increasing?

The last strand of interest for me is that old chestnut – copyright. Needless to say fanfic books occupy a grey area legally, and even if they are not being sold for profit (i.e. sales only going towards the cost of production and/or shipping), does this let them off the hook? Do they still constitute fair use? And what drives fans to sell print versions of their fanfiction despite the legal nightmare experienced by Another Hope over a decade ago?

I’m not expecting my collection to answer any of these questions. What it does make me think about however, is that fanfiction books occupy a unique place in the long history of print. One day, I hope, my collection will be the basis of a public institutional collection that can be enjoyed by all.

* I’m currently taking donations to my collection. If you’re interested in donating, please reply to this post, DM me at @ludiprice on Twitter, or email me at Ludovica.Price.1 (at) city.ac.uk. Thanks! 🙂