Image © Ludi Price CC-BY-NC-SA

Call for Presentations

FanLIS 2022 is a one day CityLIS symposium to explore the intersection between fandom, fan studies, and library and information science. May 19th 2022, online event (possibly hybrid, hosted at City, University of London).

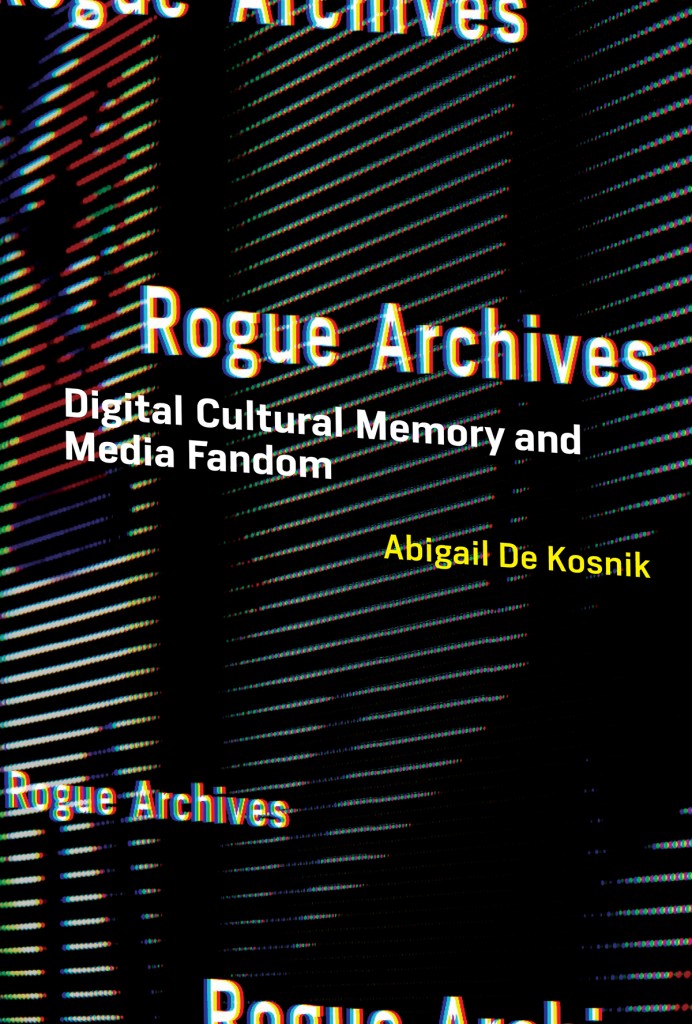

Fan studies has long been interested in the archive as a site of preservation and resistance. Examples include the work of Versaphile (2011), Lothian (2012), Brett (2013) and Jansen (2020).

In this symposium we seek to broaden this horizon, and look at fan work production through the lens of the entire information communication chain, including creation, storage, management, dissemination, circulation, preservation, meaning-making and (re)use. Creation of fanworks goes beyond the textual, and includes a multitude of formats, from the analogue and physical – costumes, figurines, dolls – to the digital – game assets, fanfilms, memes. Fandom, and its culture of collecting, ensures that it is a site of continued physicality and materiality, yet the digital has revolutionised (and continues to revolutionise) how material objects move through their lifecycle. For example, how are collections of complex fanworks, such as custom figurines, stored? How do fans manage their gaming mods? What methods do cosplayers use to disseminate their works? In what ways do non-digital fanworks circulate throughout the fan community? How is technology changing the way that fanworks are published? What are the legal implications of fanfilms? We welcome presentations that seek to answer these and similar questions, as well as ones that consider what the future of the fan information communication chain might be.

The information communication chain. @lynrobinson cc-by

In addition, we also seek to look beyond the archive solely as a site of the preservation of fan culture, and highlight the ways in which the archive – both online and offline – can be subverted by both their creators and users, be it through technology, usage. Fans themselves are instrumental in building and maintaining archives, and more than this – in developing best practice that can inform current practice within existing cultural memory institutions.

We welcome proposals for 20-minute presentations relating to the lifecycle of fanworks, from both LIS (Library & Information Science) and fan studies perspectives. We also encourage work that presents perspectives from non-Western and transcultural standpoints.

Suggested topics may include:

- Fanfiction on social media platforms

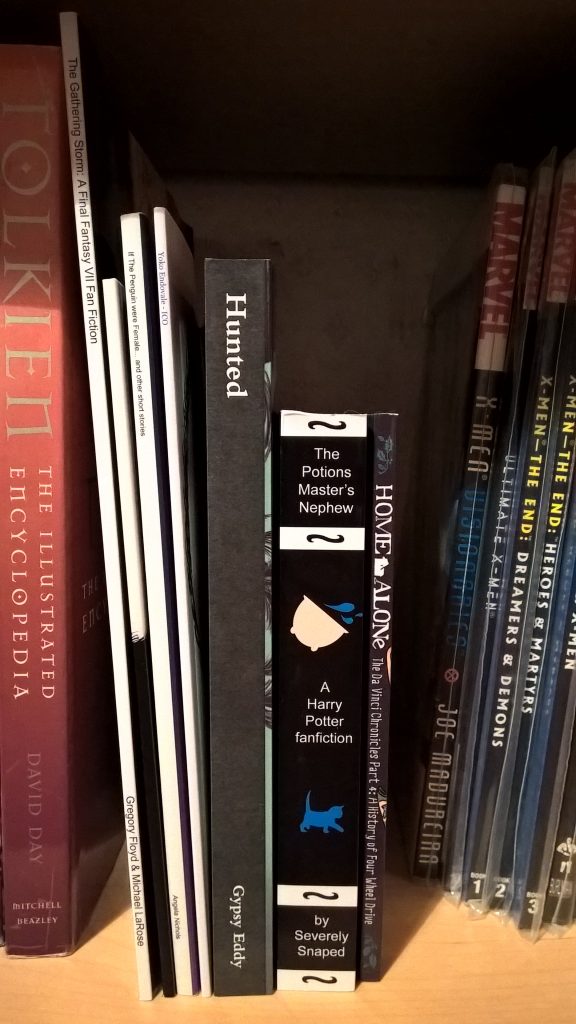

- Fan-binding

- Fan archives and their role beyond that of preservation

- Fan journalism

- Virtual reality as a medium for fanworks

- The circulation of fanworks

- Fanfiction and fanzine small presses and publishers

- Fans as archivists and curators

We are hoping to receive proposals from people from all stages in their academic career, including students and early career researchers; and also from people of colour and other cultural/non-Western backgrounds.

Please send your 500 word proposals to both Ludi Price at Ludovica.Price@city.ac.uk and Lyn Robinson at lyn@city.ac.uk by midnight on December 31st 2021.

Authors of successful proposals will be notified by January 31st 2022. The symposium will provisionally take place online on 19 May 2022 – we are looking into options for a hybrid online/in-person event.

We are also looking into open access publishing options for the proceedings of this event.

References

Brett, J. (2013). Preserving the Image of Fandom: The Sandy Hereld Digitized Media Fanzine Collection at Texas A&M University. In: Texas Conference on Digital Libraries, May 7 – 8, 2013, Austin, TX. https://tdl-ir.tdl.org/handle/2249.1/64291

Jansen, D. (2020). Thoughts on an ethical approach to archives in fan studies. Transformative Works and Cultures, 33. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.2020.1709

Lothian, A. (2012). Archival anarchies: Online fandom, subcultural conservation, and the transformative work of digital ephemera. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 16(6), 541-556. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367877912459132

Versaphile (2011). Silence in the library: Archives and the preservation of fannish history. Transformative Works and Cultures, 6. https://doi.org/10.3983/twc.v6i0.277

This is a cross post originally published on the FanLIS blog.