The following is an excerpt of a transcript of an interview between myself and the Fansplaining podcast. The interview is about my research into fan information behaviour and is featured in Episode 19 of the podcast, Cataloging Fandom. The transcript in its entirety can be read on the Fansplaining blog.

—

Fans collect… but they also catalogue.

Flourish Klink: Hi, Elizabeth!

Elizabeth Minkel: Hi, Flourish!

FK: And welcome to Fansplaining, the podcast by, for, and about fandom!

ELM: This is episode 19, Cataloging Fandom.

FK: And we’re gonna be talking to Ludi Price, who is a PhD student and a librarian and she’s working in information science and she’s going to talk about why fans are interesting in that arena.

ELM: Right, and we’re also going to take the opportunity to exorcise all of my lingering feelings about my master’s degree, which was in this realm.

FK: Oh, exOrcise, not exErcise! Exorcise.

ELM: Yeah, like a demonic possession.

FK: The power of Christ compels you kinda thing.

ELM: Yes. The power of Christ does compel me.

FK: Right.

ELM: Kinda thing. Cause I got a master’s degree in the digital humanities two years ago now, and that’s, at that university it was in the broader realm of information studies, which includes information science, librarians, archivists.

FK: All that good stuff.

ELM: Yeah it’s great stuff.

FK: So you have feelings about that.

ELM: Yeah, I have a lot of feelings about it. No spoilers.

FK: OK, should we just talk to Ludi then?

ELM: OK, um, and after we talk to Ludi we’ll read a couple of—we’ve been tagged in a few Tumblr posts recently and so we wanted to talk about one of them and we got an email that I think referenced, what episode was that where we talked with DestinationToast about yuri?

FK: It was several episodes ago.

ELM: Lord only knows. It was some time ago. So we got a thoughtful email about that so we can talk about that too.

FK: Alright, so, shall we talk to Ludi?

ELM: Let’s call her up!

FK: All right, let’s welcome Ludi Price onto the podcast!

ELM: Welcome!

Fandom at #citylis: Wolverine and Thor pinatas

Ludi Price: Hello! Thank you! Great to be here, I’m very flattered to actually be asked to come on here, because not many people know what I do or understand what I do, so yeah, it’s great to talk about it!

ELM: That’s a perfect setup for us to say “what do you do?”

LP: Ah, ok. I am many things, but part of what I do right now is I am a PhD student at City University London in Information Science. And I am actually researching the information behavior of fans. But at the same time I’m a librarian part-time. There’s kind of interconnections there. And of course I’ve also been a fan since I was a little girl.

FK: Information science—I understand, I think I understand what a librarian is at least on some level, but what is information science?

LP: Ah, OK. Actually this is a bit of a long story, because library and information science, the two disciplines, there’s a lot of overlap between them and they’re usually lumped together but they are slightly different. So I would say that information science is kind of the overarching discipline. So it’s the science of how we deal with, as human beings, information. So a lot of it is to do with the information chain, how do we create, find, seek and actually find, collate, disseminate, share, and organize information.

So it’s not actually a chain, a linear chain, it’s more like a cyclical chain, so we create, we organize, we share. Library science is kind of, I don’t want to say an offshoot of it because that’s disrespectful to librarians, but it’s, it’s the same but it’s to do with specific collections, basically. So in a library you will have a collection of some books. And then intertwined with that is the idea of documentation and documents themselves of which from my perspective you would consider fanworks as documents, and how are they collected and shared.

FK: OK so fanworks are documents, then what’s interesting about fans and the way that they deal with this stuff—it seems like everybody must, everybody encounters and deals with information, why are fans especially interesting in this way?

LP: Well, you’ve kind of hit the nail on the head because everyone in their everyday lives encounters information, from the books you read to even like bills and just general everyday things like that. Information science in itself as a discipline is more interested in kind of the more professional aspects of that, like how do certain groups deal with finding information. For example how do lawyers find information and what do they do with it. How do teachers deal with information. How do students deal with information.

And it’s only fairly recently that people have started to look into the more everyday aspects of information behavior. How do individuals deal with their own personal information, for example. And there’s also been kind of a movement towards how do people, I don’t know, people who are enthusiasts and hobbyists, how do they deal with information. Because a lot of what they do doesn’t have official channels or official sources, resources to gather information from. A lot of what they do they kind of document themselves and fandom is closely related from an information science point of view to the information behavior of hobbyists and collectors and enthusiasts and volunteers and things like that. Because they work outside of official channels and a lot of what they do is from their own kind of passion about or obsession, dare I say, with something. So yeah, there is kind of an interest in the more informal ways of sharing information in the information sciences. And fandom is a part of that that has been largely ignored, in fact almost totally ignored, and even though people are starting to pick up on that, that’s something that I’m interested in.

ELM: Yeah it’s funny because one thing that struck me a lot while I was doing my master’s was how much of the behavior that was being studied in terms of information organization or behavior seeking online was around academia.

LP: Mmhm.

ELM: And it did seem to me a huge oversight that everything I’ve always encountered in fandom seemed so much more exciting and richly organized and built as opposed to the stuff that we were studying.

FK: But, wait wait wait, actually it would be helpful to me if we could be concrete about what the stuff you’re studying is. Because I just heard a bunch about how people study, yeah, academics or whatever, but they ought to be studying hobbyists and maybe they’re beginning to, but what is the thing that you’re studying? Is it the way that people find fanfic or find fanvids or the way they bookmark them, or like… what is it?

LP: So I’ve taken on a humongous task of trying to research the whole information chain so everything from how fans find fanworks or whatever or information to do with their fandom all the way through organization of these works or whatever to actually how they share them with each other. So this is a really huge topic because no one has actually ever looked, to my knowledge no one has ever actually looked at the whole information/communication fans as fans do it, basically.

But obviously because of time and whatnot I’ve had to focus in on certain areas. So in my first year what I actually did was a literature review which was basically trying to synthesize the literatures of library and information science and fan studies and see if there was any kind of commonality or any research that overlapped on each other. So I’ve found out some stuff from that about how fans tend to go for informal information resources, how they come up with their own vocabularies, ontologies, taxonomies, things like that. They’re very generous with what they share and what they do.

FK: OK so just to make sure I understand, if you’re talking about, like, fans coming up with a vocabulary and taxonomy and stuff, so one thing you might be interested in would be like the Archive of our Own tagging system? Or vidders.net and the way vids are organized within that?

LP: Mm-hm! Yes yes.

FK: OK.

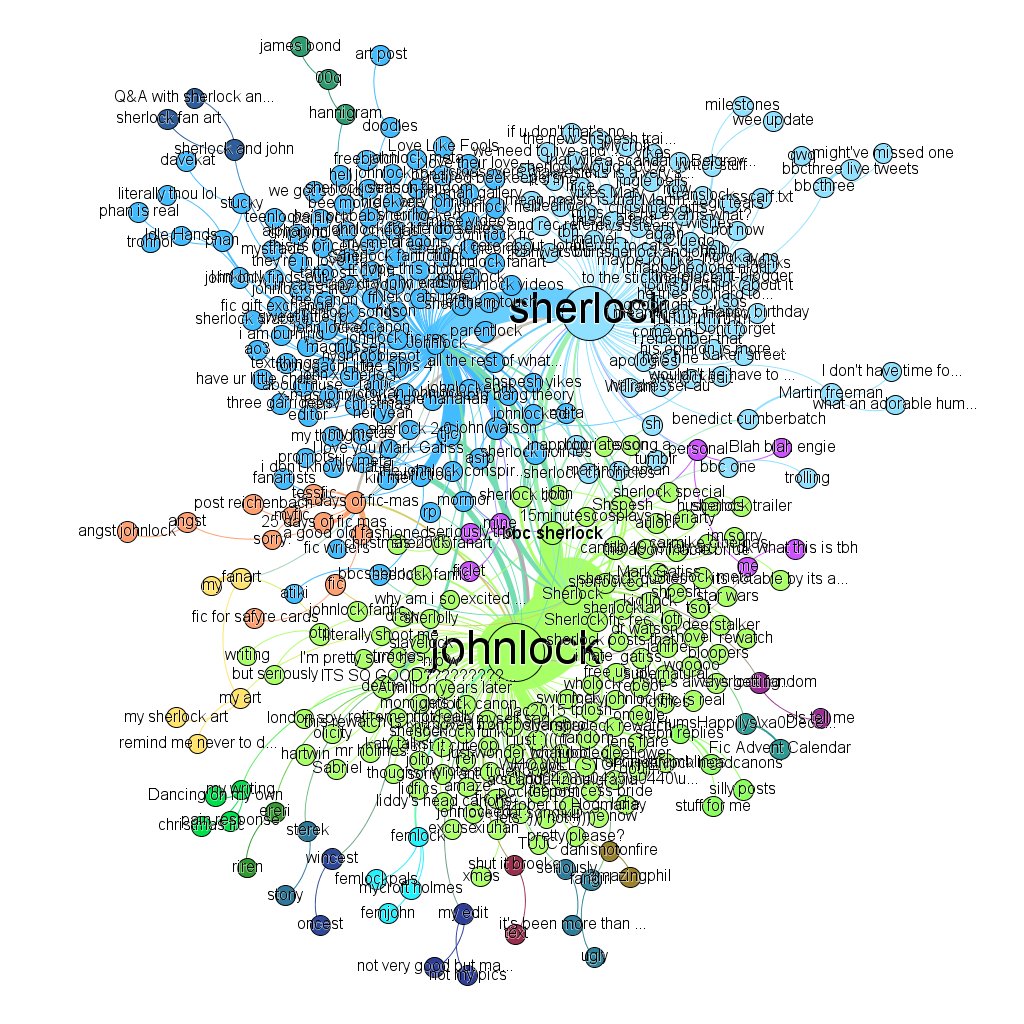

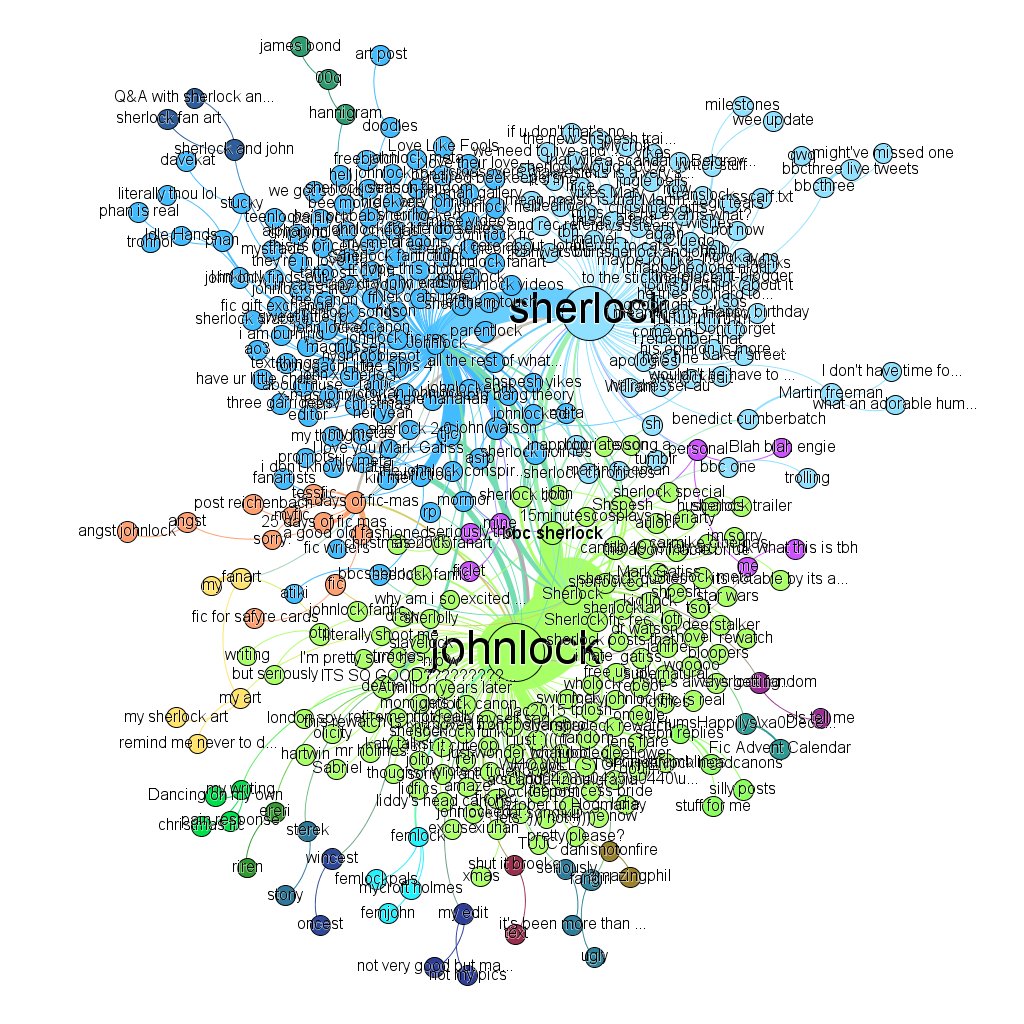

LP: Exactly. And that’s actually something that I’ve started to look at in my third year, which I’m in now, I’m actually gonna do some social network analysis but not social networks—tag network analysis of Archive of our Own, Tumblr which I just want to give a shoutout right now to DestinationToast cause she’s really helped me with that, she’s come up with some awesome Python scripts to help me collect data from Tumblr which is really difficult to do.

ELM: That’s awesome.

LP: Thanks to her, she’s great! Also I’m looking at Etsy cause another thing I’m looking at is fans who are not entrepreneurs but are fans who sell their work as well. So yeah a lot of what I’m focusing on this year is tagging practices, classification practices, vocabularies, things like that.

FK: Sorry to have cut you off Elizabeth, because I just felt like I had so many questions and you already know what she’s talking about and I have no idea!

LP: (laughs) that’s fine, that’s fine! That’s cool.

ELM: I just wanted to throw academics under the bus—but you’re an academic so maybe I shouldn’t!

LP: (laughs) If you wanna go off record that is absolutely fine! (all laugh) I do not mind at all.

ELM: No it’s just like, I often felt like, you know, say you wanna study how people communicate and organize on Twitter for example, you have to pick a subgroup, you can’t just say you know. And it just felt like the default was to pick academic Twitter, which sometimes I just felt like it was a strange way to draw conclusions. I mean I just—you can see it, in fan studies more broadly, people will in a very social science way focus on a very small fan community and then draw some, I feel like a lot of times they don’t even draw bigger conclusions because they just observe. And you’re like, or like, I would get this in DH—that’s digital humanities, Flourish, just so you know.

FK: (sigh-laughs)

ELM: They’d be like “we studied an email group of 20 people, and 2 of them said this, and 4 of them said this.” And I’d be like, OK. I just—I, you know, I guess cause I was a journalist before and I’m a journalist after and during, I don’t know what this tells us. I don’t want to put you on the spot and make you defend academic study. So. (laughs) I can cut myself off.

FK: But you are a little bit. (Ludi laughs in background)

ELM: No! it sounds like you are, it sounds like you have a bigger scope though, or maybe that’s not true?

LP: To a certain extent. I think with anything in academia, especially with anything in LIS, Library and Information Science, the problem is that it’s such a huge area. Information as you said comes into all aspects of our lives and so by its very nature, if you’re studying it, you have to focus on a certain subset or group. It’s hard to make generalizations from all that.

ELM: Right.

FK: How much do you draw conclusions from, how much of this is about just observing behavior and how much is about improving practice in other areas, so like, learning lessons in one area and then applying those lessons to another? The reason I ask is when, since ebooks have become a thing that everybody does the way that, I really personally wish that ebooks were organized in a way that was a lot closer to fanfic archives. Right?

ELM: Mm.

LP: Yep, yep.

FK: Because fanfic archives are clearly superior at actually directing you to what you wanna—I mean like this is an opinion, but. And it sometimes is irritating when people talk about the “new developing area” of this and it’s like, yeah, there’s been a ton of you know, native online texts that have existed for years that have been in archives that have had this practice. So is some of that work about just like observing even if it’s a small community, a community that seems to have made an innovation or to have something working for it and then applying that to other areas?

LP: Yeah definitely. That is actually one of the aims of my thesis is to see how this work, all these findings can actually feed into the discipline of information science itself, or not the discipline but practical uses of it, basically. Can we harness information practices, the passion, the investment that fans have in organizing their works, which is not—it can be creative but it’s just a practical way of organizing your fanworks. And fans are brilliant at doing that. I might say that some, many, most of are even better than professionals at doing it.

ELM: Yeah!

LP: And (laughs) I really want to make library users and other librarians as excited about the work they do or the resources they’re accessing as fans are. I’m really lucky that actually my PhD supervisor is really supportive and she’s really into the whole fandom herself. She really inspired me because I never even, when I finished my masters I just thought I was gonna go on a library career path, librarian career path. And then she was like, Ah, you know, have you ever thought about doing a PhD? And I was like um, kind of no maybe? And she was like, well, have you ever thought of doing a PhD about how fans deal with information? And I was like say what? This is potentially a thing?! I was like yeah, okay! And luckily she helped me with my proposal and I was lucky enough to get funding for it, so that’s really cool.

And she was really into this idea of new forms of documentation and new forms of looking at works. And I think this is a time of, even though there’s a lot of cuts in the library and information professions, in England anyway probably where you are too, there’s a great push for innovation and a great push for library and I don’t know museum archives. The users of these and memory institutions to actually get involved in helping to organize and share and get people excited about collections. I don’t know if you’ve seen things like GalaxyZoo and the World Archives Projects and stuff like that, TranscribeBentham, these projects where they want people who are really excited, amateur historians and genealogists and things like that to actually come and look at the work, transcribe it, to tag it and stuff like this.

For the library and information professions this is a really exciting and amazing thing! It’s like, we can harness the passion of the public to actually come and do this stuff for us! And it’s like, this is not a new thing, fans have been doing this stuff for years. And they are just amazing at doing this stuff!

ELM: This is interesting to me and I’d be really curious to know, and I don’t want to go too deep in the weeds, but like, so TranscribeBentham is the like—TranscribeBentham, Flourish, is (laughs) is the—

LP: Sorry about this!

FK: (laughs) What’s funny about this is I actually know a great deal about both TranscribeBentham and the digital humanities but I will be the official person who doesn’t know things about things so you can explain them!

ELM: (sputters) No it’s just like we have to explain it for the listener—

FK: We do, we do!

ELM: (doubtful) You know a great deal about TranscribeBentham, really?

FK: Well, I had a long conversation with somebody about it actually when I was in London last, so that’s the only reason I know.

ELM: With someone who was involved?

LP: Oh really?

FK: No, somebody who’s in digital humanities, about it.

ELM: So Flourish, I won’t Benthamsplain to you, but for the listeners, (laughs) Jeremy Bentham is a—

FK: (giggling) Benthamsplain!

ELM: Spiritual founder of—

FK: A corpse.

ELM: —of UCL, he’s not the actual founder of UCL but he’s like the father of UCL, he’s a what, late nineteenth, late eighteenth century early nineteenth century philosopher?

FK: And now he’s a corpse.

ELM: —real chill, and so his body is in the—(Ludi laughing in the background) He was super chill though, that’s his thing, right? Like, and (laughs) he invented the panopticon? Yeah, his body is in the hall at UCL—

FK: But not the head!

ELM: The head is in the basement.

FK: Because people used to steal the head!

ELM: Actually I heard that it was too deformed to show now.

FK: (disappointed) Oh, really? I liked my idea better that people had, like stolen it.

ELM: Anyway.

LP: It’s a good idea!

ELM: As you know, OCR, text recognition software can’t handle handwritten text, particularly from way back in the day. So they have all of his archives so they created this project where it’ll be like fun for the public. I shouldn’t make, sound so flippant, some people enjoy it. Where they transcribe his letters piece by piece and tag it very lightly with XML, and then there’s someone who works on, like, cleaning up the work of the public.

And as far as I know most of it is done by like half a dozen individuals who are just very dedicated. One woman used to watch EastEnders every night and now she, (laughing) now she transcribes Bentham. Just like, fine! That’s cool! It’s interesting! But I, one thing that really struck me, at UCL I had no less than 150 lectures about this project in my various classes. Which was a little frustrating since we all had to take the same classes.

LP: I’m sorry. I’m sorry to bring it up.

ELM: I’m traumatized.

FK: There’s other projects like this too, right? Like the New York Public Library recently did a thing with menus, which also are hard to OCR.

ELM: Right, there are all of these image projects, even Google was trying to get people to tag their shit for them. The thing that really struck me though when I hear about things like TranscribeBentham, and this gets back to what we were just talking about—I kind of bristle at the, like, academic embrace of this unpaid labor. So they’d be like, in what you’re describing they’d be like “the public is gonna love this and we have a free source of doing this work that would take a billion hours and tons of resources that we just don’t have.” I thought that was a weird strategy to kind of, fall, rely on. It was being treated like this was a default thing that was just gonna happen.

In fandom it’s different because I think there’s a lot of interesting questions of unpaid labor in fandom, but like, it never would occur to me to say like, if I was like “oh can we all look through these Sherlock screencaps to see if we can like catalog X, Y and Z,” people would just do it, and you’d be like, of course I’m doing that, I love that, you know? And so that’s the tension and the difference and I’m wondering if you’d care to comment on that. Sorry that was long.

LP: That’s OK! Yeah it’s difficult obviously there’s a tension there. And you know, I was a member of World Archives Project for like three years, and I never saw it as unpaid labor cause it was fun, it was enjoyable, and it was something that I really liked to do, and yeah, I don’t know if there’s any easy answer to it.

FK: Well isn’t there also a question about who it’s benefiting? We all do things that are unpaid labor that make, sort of, the world nicer, right? This is one of the questions about sort of the quote “emotional labor” that people go through, like, when we’re in public, we hold doors for other people even if we don’t know them.

ELM: Is that emotional labor?

FK: I think some people would say it is.

ELM: Aw, it’s not that hard, guys. Who are complaining.

FK: But also when we, you know, like with our friends we share things, in order to make a—like in an office we all agree to do things. And so there’s a question of, like, it’s one thing for Google to ask people to tag things that are then going to benefit Google’s algorithms and benefit Google’s ability to make money off of stuff and it’s another thing to be like, “here is an archive, here are the letters of Jeremy Bentham, they are public, they are for the public’s use, and in order for everybody to get more use of them, which everybody has…”

ELM: I think Google having, like, working on their algorithm for image search is vastly more beneficial to the public.

FK: Yeah but it ultimately results in, Google owns that algorithm. It may be more beneficial for the public but Google still ultimately owns it and makes money off of it.

ELM: Flourish you know that their motto is “don’t be evil,” and so…

FK: Oh yeah, cause that’s enforceable.

LP: I think they got rid of that motto now.

ELM: (laughs) Cause they started buying robotics and weaponry facilities and—

FK: But you see what I’m saying right, because on the one hand it’s beneficial for the public to do that but on the other hand you’re literally giving value to a corporation that you don’t own any part of, whereas Jeremy Bentham’s letters are, I guess I don’t know for sure that this is the case but I assume that they are in a charitable situation, right.

ELM: Cause he was just so chill, right.

FK: Well, most university—

ELM: Right, cause they just own them. UCL has them. This kind of leads back to something that I wanted to, kinda carry along with the comparison between what you were talking about before, fans’ natural inclination to organize and desire to do this stuff, and trying to bring that into the realm of you know professional information organizers, librarians and information scientists.

I have to wonder if you see a tension there too because like, just like I’m saying with I can’t imagine that anyone would want to transcribe Jeremy Bentham’s letters—and I understand that there are people that are and I’m not meaning to disparage them actually, like, thank you for your labor or your passion which is not labor! I’ve had a lot of jobs where I’ve had to organize large amounts of information and I enjoy that in my, like, OCD quelling kind of way, but it’s nothing like the joy that I get in fandom organizing and seeing the way things are organized. And I wonder if you think that that’s something that’s like, that’s surmountable, or… does that make sense?

LP: Yeah it does, it makes a lot of sense. And the more I look at the subject the more I don’t know if it’s achievable. I mean, last year I actually did a talk about trying to harness that passion in your library users that fans have, and they were just like, “we don’t see people becoming that obsessed with what we have.” And someone said, “your users would need to have a huge investment in your collection, like fans have in their fandom.” And is it possible to kind of induce that in your users? When an academic library can’t even get their academics to tag the books in their library system catalog in the area of study that they are seriously invested in and hopefully passionate about? If academics can’t be bothered to do that…

FK: Does it, do you see any difference with genre fiction? Because something I definitely wondered about was, full disclosure the thing that bothers me in the ebook universe is romance novels of which, which I think are sort of the closest officially published thing to fanfic, I mean that’s how I see them.

LP: Yep.

FK: And I enjoy them for the same, for some of the same reasons that I enjoy fanfic, and so it really grates my cheese to not be able to find romance novels in the same way I find fanfic.

ELM: Grates your cheese, Flourish, wow.

FK: Grates my cheese. And I think that there’s a lot of other romance readers who feel the same way, and I know that because romance readers tend to create their own, like, incredibly complex libraries and have extreme ebook cataloging, like, for themselves, but I haven’t ever seen that for a community out in the public.

Fandom stats – a way of looking at the tagging behaviours of fans on the internet

LP: Yeah, that kind of ties into some of the studies that have been done on hobbyist collectors and stuff like that. And a lot of what they do they do in a very insular world. The difference between the information behaviors of hobbyists and enthusiasts etc. etc. is that fans do it in a participatory way. They will organize and collect and classify and do all this stuff but they will share the fruits of their labor online and say, “this is up for grabs, you can copy this, you can use my vocabulary, whatever.”

Hobbyists don’t tend to do that. I mean they might do in a kind of physical meatspace club or something. But they don’t tend to do it in large scale, en masse movements like fans do. And what you’re saying about romance fiction and stuff like that, I’m sure there are a ton of people out there who have classified and made collections and stuff. But they don’t come together to share that. And I think probably some of the stuff that they are doing would be of great interest to publishers or the ebook creators or whatever.

And I think that this is where the intersection comes with what I’m doing with fans and what we’re saying about romance readers for example.

FK: You know it actually, while you were talking it occurred to me that maybe GoodReads is the closest thing that we have to that.

LP: Yep, yeah, I think you’re right.

FK: It doesn’t have the same robust tagging system but there are things people will make like, a collaborative list of every, here are all our favorite forced marriage romance novels. (Ludi laughs) and similarly Ravelry might be one of the few places where people who are hobbyists share information, in the knitting and crocheting and yarnmaking community.

LP: Mm.

FK: I’m sure it’s the exception that proves the rule, is what I’m saying.

ELM: The interesting question here though is, what is the aim of all this tagging? What is the aim of the way that you’re organizing? Like Amazon organizes their books in a way…

FK: It is a way.

ELM: That exists…

FK: There is some organizational principle.

ELM: They play at having all these deep subcategories like you know, like “#19 in African American-Football-Paranormal Romance.”

FK: That obviously mean nothing to people.

ELM: Which sounds like the most amazing story that I’m going to write right now. But you know, they don’t care—the question is the people doing the organizing, do they care about the person who needs to seek out this information. Like Amazon doesn’t give a fuck, right?

FK: But they should, right? Isn’t their business helping you find the thing you want to buy?

ELM: Not books. (laughs) But that’s fine. They don’t exist to sell books, Flourish! And I’ve been thinking a lot about this and maybe this is taking it too far afield, but I’ve been thinking about how fanfiction categorizes by emotions, right, and you can explicitly seek that out, so it’s a question of like… I think if you don’t understand that some people read looking for angst or hurt/comfort or fluff or whatever, whatever the equivalents would be in the professionally published world, then you’re not inclined to organize that way but maybe that’s what the person who’s seeking out the information wants, does that make sense?

FK: Right or like—

ELM: This is something that I’ve been thinking a lot about but I don’t know why I’m saying this right now.

LP: No no it’s really interesting cause I think fans are you know, they’re so into their little niche interests or kinks or whatever that fan tagging and fan classification is so highly granular, like it goes into really really specific details so you can find exactly what you want as easily and quickly as you want. And the marketing industry is not geared to that. Even though with the rise of the internet you are able to find, the internet better serves the long tail of what you want more easily, you can find really obscure stuff really easily, I think there’s still a tension with the marketing industry at large. They still kind of, it’s still broadcasting to the masses. You could have a potential really small but dedicated community that’s really heavily into this one product. And I’m not sure that many of them have quite grasped that yet. I don’t know, I’m just spitballing.

FK: This is interesting, it puts me in mind of the fact that Netflix recently made a statement that everybody in the entertainment industry is like “ohhhh!” about which is the same thing I’ve been saying for years, which is that gender and age are not good predictors of what you want to watch. Like, this seems like it should be obvious, right? Gender and age are not very good predictors of what you’re gonna want to watch, with the exception of if maybe you’re like a woman of childbearing age you’re more likely to watch instructional videos about baby care, but actually who knows, right?

ELM: Classic Netflix content.

FK: You could be a 16 year old boy who is like about to have a baby sister or brother, who knows?

ELM: Interesting example.

FK: Anyway, this is funny because it—it blows people’s minds still that this might be the case. That’s like the broadest possible categories.

LP: Yeah, it’s true.

FK: So do you think that library, do you think that libraries and the way that information is organized in there, do you think there are biases that come through from the commercial realm over into that realm?

LP: Oh definitely, definitely. I guess that goes without saying. You’ve gotta be, your books, your collection has gotta be used. You can’t just have books just sitting there or else they’ll just be a waste of space. So they get weeded if no one uses them, if they’re not in circulation. So yeah definitely. And that’s also part of what I’m interested in, is the fanwork as a collection. And as part of human culture, libraries themselves think of it as a throwaway culture. And there’s been a movement now to collect fanzines and have fanzine collections, but this is kind of, you know, the fanzine has had its heyday and it’s kind of trying to catch up with something that’s moved on so very vastly.

And so there are huge holes in libraries where fandom is concerned. And it’s a huge part of our human culture, you can’t deny that. Luckily, fans are doing a lot to preserve their own culture and I have an investment in it, so.

ELM: It sounds like there’s a disconnect though between—I feel like this is a theme we keep coming up against. Fans doing it themselves, we were just talking about this, the big episode about TV and film production, it just seems to be this gap between what the establishment is doing in any of these realms and what fans are mirroring but doing for themselves internally. Which is—or I just went on a rant about this about journalism, cause men keep writing stupid articles about fanfiction. Like, why aren’t fans doing it? But then it’s complicated.

FK: And then we have people like Ludi who are trying to bridge that gap, right?

LP: Yeah, for what it’s worth! Definitely. (laughs)

ELM: It’s worth a lot! So I don’t know, I feel like all three of us are in similar positions and I, I’m really tired right now. So I don’t know how you guys feel.

FK: I’m not tired right now, but.

ELM: Great, you had some coffee!

LP: Yes.

FK: You had coffee too, Ludi!

ELM: I haven’t had coffee yet. So one thing that I do see a lot these days, I think as fan studies gets more visibility—do you identify as a fan studies person?

LP: Not completely, I feel half and half. LIS and fan studies have widely divergent, like, backgrounds and methodologies, you just can’t—

ELM: Cause fan studies is usually, it’s social sciency, right?

LP: Yeah it’s more media and cultural studies, yeah.

ELM: OK. So that aside I think because it’s gotten so much more visibility recently I see a lot of younger people writing saying, realizing that this is like a viable thing now, yeah? —Flourish is waving at these metaphorical, or these imaginary young people.

FK: Yeah! They’re not imaginary, they’re real!

ELM: It’s exciting to think about, I am approaching what will be my 10 year college reunion, if I had known 10 years ago that this was something that I could have studied it might have changed everything, you know?

LP: Mmhm.

ELM: And so I’m wondering if you have any, like, advice or resources, I don’t wanna put you on the spot, but in terms of people beginning their academic journeys and wanting to take this stuff seriously, cause I see a lot of confusion.

LP: It’s a very kind of visceral question for me because I spent a lot of my life just feeling really unhappy with what I was doing and where I was going and then I, I just like, I was so fed up I was like “I want to be a librarian!” Because that’s what I wanted to be originally as a kid, right. So I went back to school and I did the master’s in Library Science and then I got a job as a librarian and then in the space of, the same week as getting the job the PhD proposal acceptance came through and I was like “Wow, I’m doing an information science PhD in fans!” And you know, I still can’t really get over that this is a thing. And if I’m doing this weird subject that I love so much, and I do love it despite sometimes feeling like I want to tear it apart, it’s possible, you know? It’s possible to do this if, I mean, a lot of it is luck and circumstance, I never would have gotten into it if I didn’t have a brilliant supervisor who is both a leader in her field, in the field of information science, and also is a fan herself.

But you know, if it’s something that you’re passionate about, if you’re a fan you go and do it, you write your fic, you make your vids, whatever, if you want to go into the academic area of fan studies it’s there, and if you’re passionate about it do what you do as a fan and go for it. Just try and do it, even if things are rubbish sometimes, sometimes you write crappy fic, but you love it, go for it!

ELM: That was a very positive ending!

FK: Thank you so much for coming on the podcast, Ludi, you’re like a little ray of sunshine!

LP: Aw, thank you, that’s really sweet!

FK: You really are.

LP: Thank you for having me, it’s been an awesome ride. (all laugh)

FK: Bye!

—

This post is an excerpt of a transcript originally published by the Fansplaining podcast on 10 April 2016 on their blog, Fansplaining. The actual interview can be streamed and downloaded from SoundCloud. A version of this blog post was also published on the #citylis blog.

Ten years ago Abigail De Kosnik introduced her concept of ‘archontic literature’, which describes fan texts (and indeed many other texts in the canon of Western literature) as additions to a global archive of cultural texts, an archive that writers draw upon to create their own works, thus expanding and enriching the archive that already exists (Derecho, 2006). Works such as Death Comes to Pemberley by P. D. James build upon the ‘archive’ of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice narrative; Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead builds upon Shakespeare’s Hamlet; countless tales around the world build upon the archive of ancient folklore and mythology that have enthralled us across many eons. As a student of Library and Information Science (LIS) – and an avid fanficcer – the idea of fan texts as literal and figurative documents in an ever-growing and ever-expanding archive of human culture immediately appealed to me. The appeal grew to reinforce my opinion – or intuition – that LIS and fandom are intrinsically intertwined. For if fanfiction is archontic literature, part of a grand cultural archive, who then are the archivists? The answer, of course, is the fans themselves.

Ten years ago Abigail De Kosnik introduced her concept of ‘archontic literature’, which describes fan texts (and indeed many other texts in the canon of Western literature) as additions to a global archive of cultural texts, an archive that writers draw upon to create their own works, thus expanding and enriching the archive that already exists (Derecho, 2006). Works such as Death Comes to Pemberley by P. D. James build upon the ‘archive’ of Jane Austen’s Pride & Prejudice narrative; Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead builds upon Shakespeare’s Hamlet; countless tales around the world build upon the archive of ancient folklore and mythology that have enthralled us across many eons. As a student of Library and Information Science (LIS) – and an avid fanficcer – the idea of fan texts as literal and figurative documents in an ever-growing and ever-expanding archive of human culture immediately appealed to me. The appeal grew to reinforce my opinion – or intuition – that LIS and fandom are intrinsically intertwined. For if fanfiction is archontic literature, part of a grand cultural archive, who then are the archivists? The answer, of course, is the fans themselves.