On Tuesday 21st October I went to the Internet Librarian International ’14 conference, and in between talking to everyone’s favourite information scientist superheroine (Batgirl, in case you’re wondering), I was proud to have a front row seat during the keynote speech my PhD supervisor, Lyn Robinson, gave for the Content Innovation track.

As some of you who read this blog may know, I am interested in the myriad ways in which documents can be instantiated, and the changing face of what we call ‘documents’ today. We are living in an era where the document, and what it is, is becoming increasingly blurred. Not everyone defines documents in the same way, but the so-called Information Age has made that task of defining a decidedly slippery thing – more so than usual, perhaps. With our e-books, iTunes playlists, Tumblr reclists, Wiki databases, Powerpoint slides, Twitter feeds and so on – we are inundated by documents on all sides, much of it merely the detritus of the mundane routine of our everyday lives. You might think your Tweets are unimportant and throw-away – but they’re important enough for the Library of Congress to archive, and you can request your archive if you’re desperate to read back on the minutiae of your life in the Tweetosphere.

My point is, the fluid, dynamic, sometimes ephemeral digital document is here to stay, and in the last 2 decades or so it has completely radicalised the way we view documents themselves. In many ways, the library and information profession is only just beginning to feel its way round actually dealing with the issues presented by digital documents. Many of these issues are driven by the rapid progress of technology itself, which requires a constant race with Moore’s Law, and a never-ending battle with thorny problems such as migration and emulation.

But what happens when the digital becomes passée? When it becomes to us what books are now, or codices and papyri to the ancients? What happens when the next big revolution in documentation comes along?

Lyn Robinson’s talk might give us some pause for thought, because it implied that that ‘next big thing’ was already here – or at least, it is lurking round the next corner. What is this next big thing? It’s the immersive document, and whilst it doesn’t exist yet – not entirely – in her talk Lyn gave examples in her talk of technologies that are already being developed to allow us to smell, taste and touch through wearable digital devices which are, as yet, far from perfect, but which may in future change how we experience reality and fill our leisure time.

Now this is interesting to me because as humans we are perennially attracted to this idea of unreality. According to Lyn’s presentation, there are three aspects of our lives that we as humans feel drawn to document: our dreams, our fantasies, our memories. From our ancient myths and legends, to folklore, to the fiction we read and the movies we watch, our innate desire to be drawn into the unreal has always existed, tied unequivocally to our need for escapism, for wonderment, for ways in which to creatively make sense of our inner and outer worlds. In a couple of previous posts, I talked about the immersive Punchdrunk production The Drowned Man (here and here; third part still forthcoming). This show interested me because it seemed to me to be as close to an immersive ‘virtual world’ as we could get to in an analogue, non-digital format. Its set was literally the stage for ‘another world’ where audience members strove to discover the stories of that world’s inhabitants – an impossible task since these characters lived lives whose strands could not be followed in their entirety, just as we are unable to experience the lives of those around us. What interested me was the documentation of The Drowned Man (or lack of it), and that the fans of the show would congregate online to try and fill in the gaps by providing documentation of their own. They tried to rebuild the lives of the characters by collaboratively piecing together their knowledge through what they had seen in the show.

But what if you could create an immersive record of a show? What if you could relive the life of a character by putting on the proverbial 3D headset and experiencing all the sensations they experience, thinking all their thoughts and feeling all their emotions? What if you could experience the lives of the real life people around you, not just the lives of a character in a play or a book?

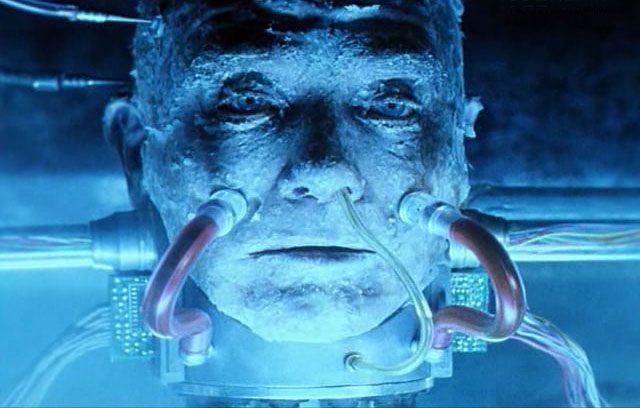

This is nothing new, of course. Popular and literary culture have been playing with this idea for at least a century. More recent entertainment media have not only exploited the trope of immersive documentation, but have looked at it in ways that might become more relevant in the future, when and if such technology comes into being. For example, the Dennis Potter TV play, Cold Lazarus (1996), analyses the ethical dilemmas associated with the recording and sharing of ones own memories. Set in a dystopian Britain of the 2300’s, a media corporation seeks to televise the memories of a 20th century writer, Daniel Feeld, whose head was preserved at death. The moral dilemma is made even more acute by the revival of the writer’s consciousness, and his awareness of the predicament he now finds himself in. There is also an interesting play on the fact that the viewer can never be quite sure how true Feeld’s memories really are, as he was in life a temperamental, creative artiste.

Still from Cold Lazarus (1996). Source: Deeper Into Movies

Then, in 2001, the first fully computer-generated movie, Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within, was released. Based on a popular series of videogames, the film kept true to its fantastical roots with its convoluted and unbelievable plot. But what is interesting about the story is that much of it hinges upon the dreams of the main protagonist, Aki Ross, who appears to have been ‘infected’ by an alien species that is threatening the planet. Thinking that her dreams might give her a clue to beating the aliens, Aki records her dreams every night, but when those recordings find their way into the wrong hands, Aki finds herself on the run.

Then there’s Remember Me, a 2013 videogame that is set in a future where people upload their memories to the cloud via an implant called the Sensen, which means that essentially your memories are no longer owned exclusively by you, but by the corporation that owns Sensen, Memorize. The game’s protagonist, Nilin, is one of a small number of people called ‘Errorists’ who are able to hack into the net and remix other people’s memories – distort, add to, or erase them. In order to complete the game, the story involves Nilin having to remix the memories of certain people in order to restore her own lost memories and bring down Memorize. The game cleverly tackles issues of privacy, intellectual property (should memories be ‘copyrighted’ like ideas?) and whether we should have the right to erase the memories we don’t like and to augment the ones we do. (We do with our bodies – should our minds be treated any differently?)

Now this may all seem far-fetched, but what all these examples (and many more besides) highlight is a need for immersive literacy. We are already facing the challenges of information and digital literacy in an age where digital information glut is the norm and so much of our everyday lives revolves around navigating the web and the cloud. When and if immersive technologies develop, we will need to consider the ethical knots they present, and, on a practical level, we will need to consider how immersive experiences are to be documented, organised, classified, indexed, catalogued and disseminated. What will the legal ramifications be? How will the role of the library and information professional have to change in order to manage such ‘documents’?

The digital leap has already caught many of us in the LIS profession unawares. Perhaps we ought to look a little further into this ‘far-fetched’ future, and think about what it might mean to deal with these potential new types of media – immersive media.