This post is written by Asma Ashraf, a Lecturer in Adult Nursing at City University of London. This is part of Asma’s assignment for EDM122 and is licensed under CC BY. Asma writes:

Publishing in open access journals – to do or not to do!

I clicked on a link to read an article on the university library website. A message appeared asking do I want to ‘Get Open Access version’ and to click on the red button. I wondered if it is correct, surely this is not a ‘paywall’. I laugh nervously as I think to myself, I do not need to worry about this, I have access!

As an academic, I am privileged to have access to most journals. As I proceed, I think to myself, is this a test? Are the module leaders trying to point out the challenges that others face? This is not a message I have seen before and I decide that it is reminding me that there are free versions available to access.

This is very telling about the challenges that those wanting to access academic journal articles experience. I have been on the receiving end of hitting ‘paywalls’ and it invokes stress. In this essay, I will be exploring whether healthcare workers should only publish in open access journals. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) in their ‘Recommendation on Open Science’ guide want scientific research to benefit all globally (UNESCO, 2023).

Let me rewind a little and explain what I mean by ‘paywall’. Paywalls are also known as digital subscriptions. It is where you make regular payments to gain access to digital content (Myllylahti, 2019). A paywall in the academic setting is when you must pay per article or choose to have a digital subscription to access peer-reviewed articles (Open Society Foundations, 2018). Paywalls are used by online news sources such as newspapers and have been used in journalism since 2010 when the phrase was coined (Myllylahti, 2019). In journalism, the reasons for paying for news are not quite the same as open access for scientific knowledge. Paywalls preventing users from accessing scientific publications are denying access to scientific knowledge and not fostering an open science culture (UNESCO, 2023).

As a nurse lecturer, I am interested in knowing what the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) website say about open access to support nurses and nursing students. There is no direct discussion about open access; however, the NMC do discuss modernising of education for nursing students. This has become more relevant particularly since leaving the European Union and new standards dictating nurse education require access to evidence and best practice (NMC, 2023).

My Hunger for Knowledge

As a nurse working in the National Health Service (NHS) since the late 1990s, I can remember attempting to access journal articles and there was a limit to the access. I wanted safe and evidence-based health research, so I was constantly searching for free access through Athens. Now called NHS OpenAthens, this provides free online access to NHS funded resources including journals and e-books to healthcare workers (Health Education England, 2024). Although the NHS funding will have paid for the research through publicly funded research (National Institute for Health and Care Research [NIHR], 2021). The cost to the NHS to access medical literature is steep. I was not able to find exact costs; however, in my search I came across an example from Daly et al.’s (2020) research discussing the merger of the library and knowledge services within one hospital NHS trust project. The cost to access one database was £11.5K (Daly et al., 2020), this is the cost for one hospital trust. There were 215 NHS hospital trusts in England alone in 2022 (The King’s Fund, 2023), and if they are all paying individually for open access this cost runs into the millions just for access to one database.

Open access was propelled internationally in 2001 after a meeting in Budapest which was sponsored by Open Society Foundations. The outcome of the meeting was to encourage researchers to publish and disseminate their findings outside of the billion-dollar academic publishing industry (Open Society Foundations, 2018). The UK NIHR in 2021 published the Open Access publication policy setting out key principles to ensure that publicly funded research is available openly (NIHR, 2021). However, this does not mean that it is entirely free, because an open access fee is paid by the NIHR to ensure the publisher allows open access.

For those with access to the internet that can look up information themselves, open access to journals means more people have access to good quality evidence-based research. This is important as a healthcare provider; however, it is important that patients can have open access to scientific information too (NHS England Workforce, Training and Education, 2020).

I believe access to information should be a priority and open access can support equity and inclusion for those that produce and use knowledge by enabling knowledge to be shared in diverse ways (UNESCO, 2023).

Blinded by Ego

Since 2012 I have published several peer-reviewed articles. In the beginning in my naivety, I was blinded by the grandeur of being a published academic. The prestige of publishing research results that I worked hard to write up in a journal with a high impact of dissemination (Chang, 2017), or so I thought.

Until recently, I did not understand the importance of publishing in an open access peer reviewed article. Whilst undertaking the Digital Literacies and Open Practice module (EDM122), I was so shocked when I learned how much money the academic publishing companies make. I watched Paywall: The Business of Scholarship. The Movie (2018) and I am still feeling angry that public money goes into funding research, yet access is restricted to the public, including those who conduct the research (Moore, 2014). Publishers receive public money. For example, the NIHR provide funds into grants they provide to ensure evidence-based research is published and available. Unless the researchers have access through their academic institution, someone is still paying and if you leave and your next organisation does not have access you lose access to your own work.

It is unfair that publishers are exploiting researchers (Moore, 2014). Researchers who submit manuscripts for publication want to have their work peer reviewed so they will pay a fee to the publisher. A group of experts will look at your manuscript and essentially proofread and provide feedback. The scam here is that those reviewing the manuscript do this for free they do not get any remuneration for their time. The publisher is taking money from those that want to publish and commissioning free work to others.

Benefits, Challenges and Limitations

I have been approached by publishers requesting me to publish and write for their journals. I remember the first time I got an email I was so excited. When I inquired further there was mention that I would need to pay money. My colleague recommended that I not entertain these publishers because they were not looking to improve evidence base (Logullo et al., 2023). Although I am now more aware of such scams, it does leave me with a bitter taste. As someone who wants to share knowledge and support nursing care, I feel sad at the manipulative nature of the publishing industry (Logullo et al., 2023). Golden open access is an approach used where authors pay the publishers fees, meaning that only those who have the funds can afford to pay. Open access journal publication still does not benefit those in lower income countries because you need access to the internet (Logullo, 2023).

On a positive note, I have worked with stakeholders including patients and advocacy groups who benefit from open access. They are better informed when making decisions and supporting others. Behind a paywall these important stakeholders would not have access to vital information. Open access journal publication also enables findings to be looked at critically (Logullo et al., 2023). This is essential to developing and evolving evidence-based healthcare practice. Logullo et al. (2023) have published their article under a CC BY comms licence, which provides others the opportunity to build on their work.

Open access journal publication also ensures that people are not duplicating work, because when they search for publications, they can see the detail of what has already been studied (Logullo et al., 2023).

Enlightened or not really!

I have developed awareness and feel that I only want to publish in open access journals going forward. Although my last four articles were all published in peer-reviewed open access journals. I did not realise the significance of this until now. I had become part of an unfair system that goes against my idea of social justice to access free resources (Bali et al., 2020).

As a nurse, equality, diversity, and inclusion plus equity are crucial for me and this is part of the UNESCO (2023) recommendations. I would like nursing colleagues and nursing students to be able to embed evidence-based practice in their day-to-day work. However, if scientific knowledge is behind a paywall this can only mean inequity and limited access for the majority (Moore, 2014).

Having previously worked in research and now academia, within the last 10 years my access to published research has been unlimited through the academic institutions have been employed with. This is great for me, however, there is a huge cost to the university.

Working as a lecturer, I do not need to have too many publications at this stage of my career. However, if I want to progress in academic rank there is a requirement for me to engage in scholarly activity and publishing in peer-reviewed journals (Cade, 2022). On a positive note, it is important that knowledge is shared openly (Cade, 2022), and I am keen to do this.

Honing My Skills

I have spent some time trying to understand where open access fits in the wider context of publishing. Is it open educational practice or part of open educational resources? Is it just about publishing in peer-reviewed journals, or does it include books? I realise now that it is both (Bali et al., 2020).

My experience is limited to publishing in peer-reviewed journals; however, having access to textbooks is important too. I have learnt whilst completing this module that public scholarship can also be done from writing blogs, using social and professional networking. These are powerful tools for disseminating knowledge such as X (formerly Twitter), LinkedIn (Bali et al., 2020; Ross, 2020) and other open platforms (Logullo et al., 2023). In terms of social justice, access to a blog or a social media post is available to more people than information that is guarded by a paywall. This means that information from these sources is not restricted to only those with enough capital to view it. However, quality needs to be considered and can be opinion rather than evidence based (Bali et al., 2020).

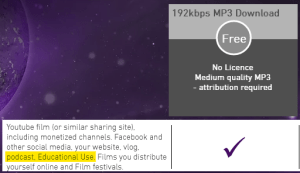

In terms of licensing for this essay, I looked through the different choices and considered the options used by previous students before me for their blog. During the game, ‘The Publishing Trap,’ which we played in class to help us better understand publishing in academia. I was nervous and reluctant to contribute because I was concerned my academic thinking would be challenged and felt I didn’t know enough. This is odd because I am usually happy to talk about my experiences and give permission for others to use my stories and examples. Yet during this game, I found that I did not want to yield, mostly because I feel like an imposter in academic publishing (Berna, 2020). This is not out of fear that someone will steal my idea, but more that I am concerned about my knowledge being questioned. This is called imposter syndrome and it is well known that this psychological block is a coping mechanism (Berna, 2020).

What will I do?

In summary, I will ask students to consider how they access publications and if they go onto publish to prioritise open access so their work can be available to everyone. I encourage students to strive for evidence-based practice in healthcare and ensure they have open access wherever they work.

Now that I have more knowledge, I will continue to promote open access and share what I have learnt. This is to ensure peer reviewed scientific information is shared and it will in turn promote digital literacy through its use (UNESCO, 2023).

The learning for this module has enabled me to delve further into my own practice and to understand the political and social need for open access publications.

References

Bali, M., Cronin, C. and Jhangiani, R.S., 2020. Framing Open Educational Practices from a Social Justice Perspective. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 2020(1), p.10. https://doi.org/10.5334/jime.565

Berna, J. S. (2020). Unblocking scholarly writing – Minimizing imposter syndrome and applying grit to accomplish publishing. Scholar Chatter, 1(1), 1 – 7, https://doi.org/10.47036/SC.1.1.1-7.2020

Cade, R. (2022). Publishing in Peer-Reviewed Journals: An Opportunity for Professional Counselors, Journal of Professional Counseling: Practice, Theory & Research, 49(2), 61-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/15566382.2022.2157595

Chang, Y.-W. (2017). Comparative study of characteristics of authors between open access and non-open access journals in library and information science. Library & Information Science Research, 39(1), pp 8-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2017.01.002

Health Education England (2024). OpenAthens [online] Available at: http://tinyurl.com/27tl9fwl [Accessed on 13 January 2024]

Logullo, P., de Beyer, J.A., Kirtley, S., M Maia Schlussel. And Collins G.S. (2023). “Open access journal publication in health and medical research and open science: benefits, challenges and limitations”. BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine https://ebm.bmj.com/content/early/2023/09/28/bmjebm-2022-112126

Moore, S. A. (Ed.). (2014). Issues in Open Research Data. Ubiquity Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv3t5rd3 [Accessed on 28 January 2024]

Myllylahti, M. (2019). Paywalls. In The International Encyclopedia of Journalism Studies, pp 1-6. Wiley Online Library. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118841570.iejs0068

National Institute for Health and Care Research (2021). NIHR Open Access publication policy – for publications submitted on or after 1 June 2022. [online] www.nihr.ac.uk. Available at: https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/nihr-open-access-publication-policy-for-publications-submitted-on-or-after-1-june-2022/28999 [Accessed on 13 January 2024]

NHS England Workforce, Training and Education (2020). [online] Available at : https://youtu.be/8WufUDDkP58?si=o2mUdHiLgAXKPCbt [Accessed on 27 January 2024]

Nursing and Midwifery Council (2023). [online] Available at: https://www.nmc.org.uk/news/news-and-updates/council-to-decide-on-modernisation-of-education-programme-standards/ [Accessed on 27 January 2024]

Open Society Foundations (2018). What Is “Open Access”? [online] Opensocietyfoundations.org. Available at: https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/explainers/what-open-access [Accessed on 13 January 2024]

Paywall: The Business of Scholarship. The Movie (2018). [online] Available at: https://youtu.be/zAzTR8eq20k?si=VRvu4v3V84JFGclL [Accessed on 13 January 2024]

Ross, P. (2020). “Blog it: Free open access to nursing education (#FOANed)”. Australian nursing & midwifery journal (2202-7114), 26 (9), p. 40.

The King’s Fund (2023). [online] Available at:

https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/audio-video/key-facts-figures-nhs#:~:text=How%20many%20NHS%20hospitals%20are,trusts%2C%20including%2010%20ambulance%20trusts. [Accessed on 27 January 2024]

UNESCO (2023). UNESCO Recommendation on Open Science [online] Available at: https://www.unesco.org/en/open-science/about [Accessed on 27 January 2024]

This blog post is written by Ami Pendergrass who is a MSc student in Library and Information Science at City and recently completed my module EDM122. Her essay is on the introduction of Rights Retention Strategies to Open Access in Higher Education. She writes……

This blog post is written by Ami Pendergrass who is a MSc student in Library and Information Science at City and recently completed my module EDM122. Her essay is on the introduction of Rights Retention Strategies to Open Access in Higher Education. She writes……