This blog post is written by Ami Pendergrass who is a MSc student in Library and Information Science at City and recently completed my module EDM122. Her essay is on the introduction of Rights Retention Strategies to Open Access in Higher Education. She writes……

This blog post is written by Ami Pendergrass who is a MSc student in Library and Information Science at City and recently completed my module EDM122. Her essay is on the introduction of Rights Retention Strategies to Open Access in Higher Education. She writes……

As a current Library and Information Science (LIS) Student, I am learning of the importance of how my colleagues and I need to be at the forefront of determining the future of our library services. One of the key topics of discussion is Open Access (OA). OA is the mechanism that makes research publications freely available, free of charge, and free from most copyright restrictions to anyone who can benefit from them (see JISC, 2019; City, 2023a; Creative Commons, 2024). In simple terms, OA is the way to bring the depth of research and analysis out from behind (mostly expensive) paywalls and share it. This benefits not only fellow researchers who can learn and build from it, but the public at large, where people can use it to create new ideas, change opinions or even save lives.

In the case of higher education (HE), one of the challenges of OA, however, has been in finding a long-lasting working relationship and strategy between HE, authors, and academic publishers that simultaneously provides that kind of necessary access while also mitigating the significant impact it will have on publishers and publishing models (Moskovkin et al., 2022, p. 176; SPARC Europe, 2023). An area of keen interest to me as both a LIS student and a former lawyer and negotiator is the recent adaptation of a Rights Retention Strategy or RRS by HE institutions in the UK as a tool to force OA quicker. RRS is a process that uses Creative Commons licensing to assign copyright, giving a way for authors to ensure that they can deposit their work where they see fit including OA which is still being limited by many academic publishers.

As someone who plans on working in this space as a librarian, understanding this issue for myself and for my users is critical. Below, I will discuss the background of OA and how HE institutions have moved to RRS as a tactic to bring OA quicker. I will then provide my views on RRS as a strategy and what we as librarians can be doing to help support our users in manoeuvring through this potentially complicated process.

A Brief History of OA and Transformative Agreements

Before we can talk about what rights retention strategy (RRS) is, it helps to understand where we’ve been. OA itself was born at the cross-section of several big issues. First, a large portion of important research projects are publicly funded. However, with the shift of published academic research from print to digital, much of that publicly funded research came to be behind paywalls, which made access to it by other researchers (and sometimes even the authors themselves) difficult and expensive (see City 2023a; REF, 2023; Plan S, 2021). This would mean that research may never be acted upon or could be duplicated (Moskovkin et al., 2022, p. 176). And as became immediately apparent with COVID19, resolving complicated, international issues meant needing access to the latest research quickly and cost-effectively to save lives (Moskovkin et al., 2022, p. 176; SPARC Europe, 2023). Many funders, including COAlition S and UK Research and Innovation, now require OA publication as a result (Plan S, 2021; REF, 2023; City 2023a; City 2023b). Second, HE institutions and libraries were dealing with the clash between an astronomical rise of subscription journal prices (with one statistic showing an eightfold increase in costs from 1984 to 2010) and shrinking budgets that put pressure to bring those costs down (Borrego et al., 2021, p. 216). A transition to OA was seen as the solution to both problems.

To find a ‘middle ground’, HE institutions and academic publishers (who were not already OA) negotiated an arrangement called a transformative agreement (TA’s) to help those publishers who were closed access (or whose material was behind a subscription paywall) to ‘transform’ from subscription to fully OA (see City 2023a; REF, 2023; Plan S, 2021). TAs have developed into three main types:

- Pre-transformative – this is where the journal would still have a paywall but would allow a limited number of articles to be published OA, usually by using a discount or voucher system to track.

- Partially-transformative – this is where the journal would offer two types of fees, a ‘read’ fee or the normal subscription fee and a ‘publish’ fee or what is referred to as an article processing fee or APC to publish OA (and these too are usually limited in number).

- Fully-transformative – this is where the journal would provide a single fee for both subscription and APC and this would allow for unlimited OA publication.

(Borrego et al., 2021, p. 216). These types of TAs (above) created in many cases a new type of journal, the ‘hybrid’ journal, where the journal was partially OA and partially subscription. These hybrid journals created two main routes to OA publishing: green access (which while free, can subject the author/institution to a publisher embargo period or a limitation on the number of articles that are eligible for OA publication); or gold access (which has no limits (such as embargos) but is a ‘pay to publish’ model where APCs are required) (City 2023a; City, 2023b).

TA’s, and the hybrid journals created as a result, were initially viewed as a temporary solution to promote an orderly transition from the historic subscription model to OA. However, the transition has been slow, expensive, and not exactly temporary (Borrego et al., 2021, pp. 219, 226; Plan S, 2021; Moskovkin et al., 2022, p. 169). An example of this can be seen with the lack of impact of article processing costs (APC) driving down the costs of overall fees. APCs were to provide a transitional fee arrangement that shifted the cost from subscription to publishing so that works could be published OA sooner rather than later (Asai, 2023, p. 5166). The idea was that the ‘fees’ would be constant while OA publishing would increase, ultimately resulting in subscription fees decreasing and being replaced by APC (Asai, 2023, p. 5166). However, as multiple studies show (Asai, 2023; Borrego et al., 2021; Moskovkin et al., 2022) these fee arrangements effectively functioned as a ‘double dip’ for publishers, requiring universities to pay to publish while simultaneously paying again a subscription fee (which seemed to be ever increasing) to access the same article. Far from being cost neutral, hybrid journals were increasing costs (see Moskovkin et al., 2022, p. 167; Parmhed and Säll, 2023, p. 6).

Enter Rights Retention Strategy

As it became apparent that transformative agreements were becoming more transfixed, HE institutions began to look for new solutions to promote OA publication, while addressing the continued increase in costs. One of those ‘solutions’ is the adaptation of rights retention strategies (RRS). Under most academic institution’s RRS policies, authors are asked to declare a Creative Commons license called a CC BY in the acknowledgement and cover letter of the authors accepted manuscript, prior to submission to a journal (City, 2023a; City, 2023b: Rumsey, 2022; UCL 2021). A CC BY license enables a work to be re-used, distributed, remixed, adapted, and build upon by anyone, so long as it includes attribution to the author (Creative Commons, 2019). The upfront notice to publishers plus the adaptation of the CC BY license, in essence, should mean that the author is free to distribute their work openly and that the publisher cannot override assignment through a subsequent agreement (UCL, 2021; Plan S, 2024).

So, why this tactic? It could be argued that RRS was born out of an old problem. One aspect of the old subscription model was the assignment of full copyright to publishers (exclusivity) as pre-condition for publication, which had significant impact in not only stripping authors from their intellectual property but also financial implications in locking HE institutions into having to pay for a subscription for the same authors to access their own material, ‘arguably a form of academic exploitation’ (Rumsey, 2022). RRS is a pushback against publishers requiring authors to agree to exclusivity by allowing authors to retain their copyright using Creative Commons licensing, with the goal of immediate publication without embargo and bypassing APCs (Plan S, 2020; City, 2023a, Rumsey, 2022; n8 Research Partnership, 2023; Moore, 2023, p. 1). RRS restores control to the author on ‘when, how and to whom research findings are disseminated’, maintaining ownership where it belongs, with the author and not a third-party provider (Rumsey 2022). RRS is not new; universities, such as Harvard (the original RRS model) have had an RRS policy since 2008 (Rumsey, 2022; Moore, 2023, p.3).

Is RRS the ‘Opening’ We Need and How can Libraries Support ?

As with any new ‘thing’, there are positives and negatives. RRS can have a positive impact in not only speeding up OA publication but by serving as an effective wedge issue to gather the HE institutions and publishers back to the table to find a better way to bring balance between reasonable access and reasonable compensation (Moore, 2023, p. 7). However, RRS is not without problems. Rightly or wrongly, many publishers are viewing the move to RRS as a direct violation of their service agreements and that has placed authors in a difficult situation between the publishers who do not support it and the funders who are increasingly demanding it (Khoo, 2021). The recent Cambridge and Edinburgh pilot study of RRS provides a good example of the ‘trouble’ authors are facing. In response to the uptick in the use of RRS, the studies found that publishers have increased desk rejections; rerouted works to OA or less prestigious journals; provided incorrect or misleading advice; presented fees at the last minute; or coerced authors into signing their copyright away anyway ( Khoo, 2021, p. 3; Rumsey 2022; University of Cambridge, 2022; Open Scholarship, 2022). However, the fight is really between HE institutions, the funders, and the publishers who, like it or not, do have a legitimate (though overpriced) function to deliver, not the authors themselves. Asking the author to ‘hold the line’ is a bit akin to asking the child of two warring parents in a divorce to provide the solution to all the family’s marital woes (see Khoo, 2021 and Moore, 2023).

As a future librarian on the ground (and hopefully at the table), I offer a few suggestions. First, from the bargaining standpoint (and my old lawyer days), RRS is a great starting point but, arguably, what RRS is doing is using copyright to bypass aspects of these TAs that HE institutions do not like. This is a blunt instrument that in the long term may damage our relationship with publishers. What we ultimately need is better agreements that align charges to actual delivery by publishers (see Borrego et al.,2021; Khoo, 2021; SPARC Europe, 2023; Moskovkin et al., 2022). So RRS is a means, not an end. HE institutions should endeavour, as soon as possible, to work together to get back to the table and use RRS as a wedge to promote agreement on a better vision and longer-term future for both. We ultimately still need each other and we only get there by talking.

However, talks and negotiations take enormous time and effort. As a librarian, to support our users now, the quickest and most valuable thing we can do is to provide in-depth training on copyright that helps users understand their rights and how to tactically use their assignment in copyright to get the deal they want. I believe anytime we ask someone to assign a legal right away, we should support them to the fullest with education and tactics so that they can make educated and sound decisions, whether they use Creative Commons or sign an exclusivity agreement. We should also partner with our HE librarian counterparts across UK institutions to study RRS best practices, not only from the standpoint of how we manage RRS as librarians but also to help our users to understand what works and what does not as they interact with publishers. RRS policies by themselves is not enough to really support our authors. Training and best practice guidance is vital to make this work.

RRS may not be the opening we hoped for but it is a wedge in the door to a better future. I believe as a librarian, our biggest contribution is to help educate and advocate for what RRS is ultimately trying to achieve, a long-lasting partnership with our publishers for an OA future.

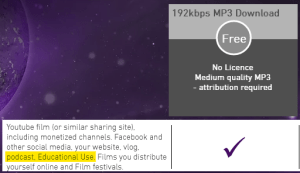

This article is published with a CC BY license that enables re-users to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the author. This license is for commercial use only. For mor information, see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Works Cited:

Asai, S. (2023) “Does double dipping occur? The case of Wiley’s hybrid journals”, Scientometrics, 128(9) pp. 5159-5168. Available at: https://www.doi.org/10.1007/s11192-023-04800-8 (Accessed: 13/01/2024).

Borrego, Á, Anglada, L., and Abadal, E. (2021) “Transformative agreements: Do they pave the way to open access?”, Learned publishing, 34(2), pp. 216-232. Available at: https://www.doi.org/10.1002/leap.1347 (Accessed: 13/01/2024).

City, University of London (2023a) Understanding Open Access. Available at: https://libguides.city.ac.uk/understanding-oa (Accessed: 11/01/2024).

City, University of London (2023b) Open Access Policy. Available at: https://libraryservices.city.ac.uk/about/policies/compliance/open-access-policy (Accessed: 12/01/2024).

Creative Commons (2019) About CC Licenses. Available at: https://www.creativecommons.org/share-your-work/cclicenses/ (Accessed: 11/01/2024).

Creative Commons (2024) Open Access. Available at: https://www.creativecommons.org/about/open-access/ (Accessed: 12/01/2024).

JISC (2019) An Introduction to Open Access. Available at: https://www.jisc.ac.uk/guides/an-introduction-to-open-access (Accessed: 12/01/2024).

Khoo, S.Y. (2021) “The Plan S Rights Retention Strategy is an administrative and legal burden, not a sustainable open access solution”, Insights, the UKSG journal, 34(1).

Moore, S.A. (2023) “The Politics of Rights Retention”, Publications (Basel), 11(2) pp. 28. Available at: https://www.doi.org/10.3390/publications11020028 (Accessed: 13/01/2024).

Moskovkin, V.M., Saprykina, T.V., and Boichuk, I.V. (2022) “Transformative agreements in the development of open access”, Journal of Electronic Resources Librarianship, (34) 3, pp. 165-207. Available at: https://www.doi.org/10-1080-1941126X.2022.20999000 (Accessed: 13/01/2024).

N8 Research Partnership (2023) Why Northern Universities are Taking a Stand on Rights Retention. Available at: n8research.org.uk/why-northern-universities-are taking-astand-on-rights-retention/ (Accessed: 11/01/2024).

Open Scholarship (2022) Rights Retention Policy: An Update after 9 months. Available at: https://libraryblogs.is.ed.ac.uk/openscholarship/2022/10/14/rights-retention-policy-an-update-after-9-months/ (Accessed: 12/01/2024).

Parmhed, S. & Säll, J. (2023) “Transformative agreements and their practical impact: a librarian perspective”, Insights, the UKSG journal, 36(12). Available at: https://www.doi.org/10.1629/uksg.612 (Accessed: 13/01/2024).

Plan S (2020) cOALition S develops “Rights Retentions Strategy” to safeguard researchers’ intellectual ownership rights and suppress unreasonable embargo periods. Available at: coalition-s.org/coalition-s-develops-rights-retention-strategy/ (Accessed: 09/01/2024).

Plan S (2021) Principles and Implementation. Available at: https://www.coalition-s.org/addendum-to-the-coalition-s-guidance-on-the-implementation-of-plan-s/principles-and-implementation/ (Accessed: 13/01/2024).

Plan S (2024) Plan S Rights Retention Strategy. Available at: https://www.coalition-s.org/rights-retention-strategy/ (Accessed: 12/01/2024).

REF (2023) REF2021: Overview of open access policy and guidance. Available at: https://archive.ref.ac.uk/media/1228/open_access_summary_v1_0.pdf (Accessed: 12/01/2024).

Rumsey, S. (2022) Reviewing the Rights Retentions Strategy – a Pathway to Wider Open Access? Available at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2022/10/26/reviewing-the-rights-retention-strategy-a-pathway-to-wider-open-access (Accessed: 23 January 2023).

SPARC Europe (2023) Opening Knowledge: Retaining Rights and Open Licensing in Europe 2023. Available at: https://www.knowledgerights21.org/reports/opening-knowledge-retaining-rights-and-open-licensing-in-europe-2023/ (Accessed: 13/01/2024).

UCL (2021) Wellcome, transformative agreements and rights retention. Available at: blogs.ucl.ac.uk/open-access/2021/03/05/wellcom-transformative-agreements-and-rights-retention/ (Accessed: 12/01/2024).

University of Cambridge (2022) Rights Retention: Publisher Responses to the University’s Pilot. Available at: https://unlockingresearch-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=3361 (Accessed: 13/01/2024).