*This blog post is in response to a lecture on publishing and the author, which was part of the #citylis Libraries and Publishing in the Information Age module (INM380).

If there was ever a poster child for self-publishing, fanfiction would probably be it. One could talk for hours about how the internet has ‘democratised’ (self-) publishing and given everyone the potential to have a voice. Not everyone has a voice, of course; but the digital divide is quite another issue and isn’t the object of this post. What is the object is how the internet has given a certain sub-section (or subculture?) of the creative community – fans – a very loud voice. Certainly, when one thinks back and remembers the days when self-publishing was relegated to those who could afford to have their work published by a so-called ‘vanity press’, and compares it to the situation nowadays – when online, indie publishers abound – it’s not so hard to believe that perhaps publishing has been democratised.

To recount a short, personal anecdote – when I was in secondary school, a girl in the class two years below mine got her book self-published. It was a fantasy book, with a lovely cover, that she gave to the English teacher to read. She must’ve been about 13 at the time; I’d just about finished my own first (terrible) novel that I knew would never get to see the light of day (thankfully, as it turns out). I distinctly remember thinking how terribly unfair it was that she could have a book published just because her parents could afford it. Nowadays, she probably would have joined the floods of authors and writers who use online self-publishing sites such as Lulu.

I hope you don’t think I’m taking pot shots at Lulu. Lulu is a great tool for writers who want to get their work out there and who, more importantly, desire the legitimacy that a print book available on the market bestows. But what Lulu can’t do is bestow fanfiction authors with the same privileges – at least not in theory. And what particularly interests me about self-publishing in the so-called Information Age is how it has affected the behaviour of fans, particularly fanficcers.

Some of the first people to migrate to the internet when it first went mainstream were fans (Jenkins, 2006). The internet gave fans the opportunity to congregate in spaces in ways that were not possible in an analogue world. It also gave them a place to share their creations – so-called fanworks – with a much larger audience than was previously achievable. Years before blogging became the rage, FanFiction.net was providing a combined online self-publishing platform and repository for a small but growing number of fans. It is now the biggest fanfiction website in the world.

As a repository and a digital distribution platform, FanFiction.net has been joined by other sites such as Archive of Our Own (AO3) and WattPad. These sites allow amateur writers to share their fanfiction for free, even allowing the ability to add book covers in some cases. This does not provide authors with the prestige of a physical object that the vanity presses may have provided; but the advantages are that you have complete control of your creation – from content organisation through in-built tagging and categorising systems; to the ability to access your readership directly via a comments system or private messaging; to the advantage of recruiting from your readership editors or, as they are known in fan circles, ‘beta-readers’. And all this at the price of no more than simple registration.

Self-publishing of fanfiction has even moved onto social media platforms such as Tumblr and Twitter. Indeed, it seems that fanfiction has never been more visible in its entire history. One only needs to mention 50 Shades of Grey to give an example of fanfic that has subsequently been published and gone mainstream – though only after being completely stripped of all its references to the original work it was based on, The Twilight Saga. And indie publishing houses, such as Big Bang Press, are actively and exclusively recruiting fanfic authors to write original works for them, knowing that some of the most popular of these authors already have a readership numbering in the hundreds, thousands, or even millions (Eddin, 2014).

But this is nothing strictly new.

Fanfic writers have been making the jump to ‘profic’ (or professional fiction) for decades now (Pugh, 2004). What has changed is the way in which fanfic writers have a greater control over their creative output, the readiness with which they can find an outlet for their work, and the easiness with which one might find and maintain a readership. Making the jump to profic is no longer the only way for a serious fanfic writer to gain a wide and influential audience. Part of the success of 50 Shades of Grey was down to the lobbying and active engagement of the fans of the original fanfic, Master of the Universe – for instance, via GoodReads reviews and a mother’s social group, Divalysscious Moms, holding the launch party that got author E. L. James noticed by the traditional publishing industry. (Peckosie & Hill, in press; Souccar, 2014).

But what about fanfic writers who are serious writers and want to make a living from their craft without giving up their original creative vision?

If a fanfic writer is lucky, they may get to work with the producers of a franchise writing licensed novels for a general market (e.g. for the Star Trek novels and Star Wars expanded universe, etc.). But these are written under tight controls and the author is always answerable to the satisfaction of the company it writes for (Pugh, 2004).

So what about actually self-publishing fanfiction?

Self-publishing fanfiction in print form is a controversial concept because if you make money from it, you are liable to receive a cease-and-desist letter from a company for making profit from characters that they own the rights to. Via Lulu, I sell print copies of my fanfiction – but these books are not available on the general marketplace and I get no money for sales made. However, in preparation for a talk on this subject, I became curious to find out whether there was any fanfic being sold on the marketplace, despite the legal issues. So I went onto Amazon, and typed in ‘Rogue and Gambit’ (my ‘fan ship‘ or OTP). I was quickly able to find a book for sale, which, incidentally, appeared to have been self-published through Lulu. I was curious. So I bought the book.

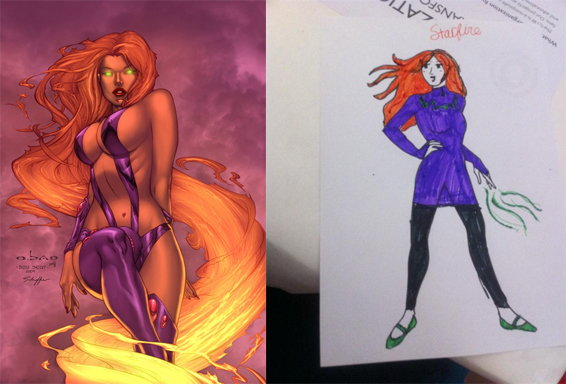

The next morning, thanks to Amazon Prime, the book was in my hands. In it were collected short stories, using a wide variety of characters from the Marvel and DC franchises. No copyright disclaimer was given – copyright was, in fact, claimed by the author herself. I was rather shocked by the blatant disregard for licensing laws; but it made me think. If it’s so easy to fly under the radar like this, how many others are getting away with making money off the intellectual property of others? Does this make even more of a case for the fact that our copyright laws are horribly outdated? (My personal opinion: YES). Should these self-publishing houses and platforms have a duty of care to vet this stuff before it gets published? And lastly, on a related tangent – in the middle of the 50 Shades of Grey furore over inaccurate depictions of BDSM – do publishing houses in general have laxer sensibilities towards fanfic that has been adapted into profic, than they do towards ‘regular’ fiction? Is the bar to quality set higher or lower? Or, indeed, does it even matter?

References

- Eddin, R. (2014). Publishers are warming to fan fiction, but can it go mainstream? WIRED [online]. Available at: http://www.wired.com/2014/02/fanfic-and-publishers/ [Accessed 12 February 2015].

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers and gamers: exploring participatory culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Peckosie, J., & Hill, H. (in press). Beyond traditional publishing models: An examination of the relationships between authors, readers, and publishers. Journal of Documentation 71 (3). (Accepted for publication 29 July 2014).

- Pugh, S. (2004). The democratic genre : fan fiction in a literary context. Bridgend : Seren.

- Souccar, M. K. (2013). Divalysscious Moms: Killer maternal instincts. Crain’s New York Business [online]. Available at: http://www.crainsnewyork.com/article/20130127/MEDIA_ENTERTAINMENT/301279982/divalysscious-moms-killer-maternal-instincts [Accessed 19 February 2015].