I am Sandra Vucevic, a Visiting Lecturer at City, St George’s University of London, teaching introductory quantitative modules. This reflective essay, submitted for the EDM122 module of my MA in Academic Practice, explores my experiences navigating the complexities of digital literacy in the teaching of quantitative methods.

In preparing for this essay, I realised that my understanding of digital literacy, while frequently used, was perhaps incomplete. Therefore, I will begin by outlining what I consider to be the most comprehensive recent definition, as offered by Radovanovic (2024, p.2).

“Digital literacy encompasses the set of capabilities and skills and values; it is the ability to mindfully analyse, process, design, and produce information; to develop and employ critical thinking skills in the landscape of mis- and disinformation practices at digital platforms; to create, collaborate, engage, and communicate with others in a respectful and meaningful way; to understand the algorithms’ mechanisms and strategically interact with artificial intelligence and similar platforms; to use the internet in a responsible, safe, and ethical manner having in mind the data privacy and digital footprint; to be accountable and respectful for one’s actions online, and to be able to understand the consequences of one’s behaviour.”

I find this definition particularly compelling because it acknowledges the complex interplay of technical skills, critical thinking, and ethical considerations that constitute digital literacy. It moves beyond a simplistic understanding of digital literacy as mere tool-based competence and recognizes the broader social and cultural implications of technology use.

Early Encounters with the Digital Literacy Gap

Growing up surrounded by technology, I consider myself a digital native (Prensky, 2001), which perhaps led me to overestimate others’ digital fluency. My background in computer engineering and early coding experience have made many digital tasks feel intuitive, so it’s always a stark reminder of the digital divide when students struggle with what seem like basic operations. I recall a student who attempted to centre a title in Word by using the spacebar. It was a small thing, but that single incident highlighted the digital divide that I’ve come to realise is far more widespread than I initially thought, particularly within universities. It’s become clear that many students starting university lack the digital skills necessary to truly participate in a digital learning environment (Russo & Emtage, 2024).

My initial surprise at the mentee’s spacebar struggles was quickly reinforced by everyday teaching experiences. I remember one student emailing me with “Hi bro, where to find assessment instructions?” While that example was quite informal, it wasn’t entirely unusual. Many students were clearly unfamiliar with email etiquette. I also noticed how few of my 350 students had LinkedIn accounts when I suggested they connect with me there. Students often struggled with software installation, simple tasks like cropping screenshots, and formatting documents. Referencing proved a major hurdle for their assessments. I encountered numerous instances of students copying entire paragraphs without attribution, using unreliable sources (e.g., the Daily Mail) and referencing the same literature inconsistently. Formatting inconsistencies, like varying font sizes within paragraphs, were also commonplace.

Beyond these technical skills, I also observed a broader struggle with critical thinking and information evaluation. Some students couldn’t distinguish credible online information from ‘fake news’ or separate opinion from fact. Others struggled to interpret even simple graphs. These issues weren’t simply about a lack of knowledge; they reflected deeper gaps in digital literacy and, consequently, academic preparedness.

Teaching introductory quantitative modules for the past four years has been a steep learning curve. I initially assumed students possessed the necessary digital and academic skills to navigate university systems and engage with the material. I believed my role was simply to deliver the curriculum. How wrong I was! Students consistently faced digital challenges, from accessing university email and Moodle to navigating library resources. These recurring difficulties revealed a substantial digital literacy gap, especially concerning the digital tools crucial for quantitative data analysis. I quickly realised that simply explaining statistical concepts wasn’t enough; I had to explicitly teach the underlying digital skills they lacked. “Working with data is a cluster of competencies rather than a single skill” (Ruediger et al., 2022, p. 10), and my students needed support across the board, from file management and software proficiency to data wrangling, analysis, and discipline-specific methodologies. This often-consumed significant class time, frequently at the expense of core statistical content. I often felt, and still feel, torn between teaching essential software skills and core disciplinary knowledge – a tension Ruediger et al. (2022) identify as a common concern among instructors.

Challenging Assumptions About Digital Natives

The idea of the digital native (Prensky, 2001) – that young people, having grown up surrounded by technology, are inherently fluent with digital tools, unlike digital immigrants – is a widely held view. However, this concept has been criticised for its oversimplification (Riordan, Kreuz & Blair, 2018; Bennet, Maton & Kervin, 2008). Different studies have found no significant difference in digital skills or literacy between young people and older generations (Akcayir, Dundar & Akcayir, 2016; Guo, Dobson & Petrina, 2008). This prompts me to examine my own assumptions: have I, too, generalised about young people’s digital abilities based solely on age?

Moreover, young people’s apparent confidence with devices like smartphones often hides gaps in their ability to use technology effectively for academic work (Passey et al., 2018). I’ve seen this myself: many students who are constantly using their phones struggle with basic tasks like formatting documents, understanding data charts, or creating academic references. This highlights that familiarity with technology doesn’t equal competence. It reinforces the need for explicit instruction in digital literacy skills, even for students who appear tech-savvy. Research indicates that factors such as socio-economic status, education, and access to technology are far more influential determinants of digital competence than age (Kincl & Strach, 2021; Pangrazio, Godhe & Ledesma, 2020; Creighton, 2018; Selwyn, 2009). This is consistent with my own experience of observing varying levels of digital proficiency among students.

Another pervasive myth is that educators must be technical experts to support students’ digital learning. Assuming students’ inherent digital superiority can create undue pressure on academics (Radovanovic, Hogan & Lalic, 2015), as both staff and students often lack confidence using technology for education, despite personal comfort with it (Garcia et al., 2013). Levy (2018) rightly argues that educators don’t need to master every single tool; instead, they should focus on facilitating meaningful engagement with technology. This is something I encourage in my graduate teaching assistants – it’s about empowering effective use of technology, not just demonstrating button-pressing.

The myth that students inherently know how to learn effectively online is compounded by universities often taking digital literacy for granted (Murray and Perez, 2014). Many students lack the initiative to meaningfully explore educational technologies (Burton et al., 2015). The COVID-19 pandemic exposed this, highlighting the impact of the digital divide on educational equity (Summers, Higson & Moores, 2022; Bashir et al., 2021; Pentaris, Hanna & North, 2021). This divide, exacerbated by differing digital experiences, resources, and usage, disproportionately affects students from disadvantaged backgrounds. As Radovanovic (2024, p .5) argues, this digital poverty affects the entire learning ecosystem, becoming magnified during crises like COVID-19, where a lack of digital skills and access leads to digital exclusion. The pandemic underscored the urgent need to address this divide and abandon simplistic assumptions about digital fluency.

Prensky (2001) also described digital natives as adept multitaskers thriving on instant gratification. However, this is often just task-switching, which can negatively affect learning (Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 2017). I’ve certainly observed this myself; students constantly switching between tasks seem to overload their cognitive resources, hindering their ability to focus and process information effectively. While students may have preferred delivery modes or feel comfortable with certain technologies, I’ve found that establishing clear ground rules for classroom technology use is essential. It’s not about simply giving them free rein with devices, but about creating a conducive learning environment. Setting clear expectations for classroom technology use has been key to fostering a more focused and productive learning environment.

Beyond these myths, educators can develop more effective strategies by shifting from assumed competence to fostered competence. This is a continuous process requiring reflection and professional development. Having established the need to move beyond these misconceptions, it is imperative to consider how digital literacy can be effectively integrated into the curriculum.

Bridging the Gap: Integrating Digital Literacy into the Curriculum

Integrating digital literacies is challenging because they are not just technical skills but learned practices that build upon those skills (Bennet & Folley, 2018). This distinction, between the technical aspects of a tool (skills) and its purposeful application (practices), is crucial for effective digital literacy instruction.

Reflecting on my own practice, I’m now more confident that I was four years ago in understanding my students’ digital literacy needs but effectively addressing them requires a strategic approach. The most effective method is for academic teachers to take full responsibility for integrating digital literacy development directly into the core curriculum (Nicholls, 2018). Rather than relying solely on external support services (IT, librarians, academic skills teams), I have found it more effective to embed digital literacy instruction directly within my teaching. I’ve realised that small, targeted interventions can significantly improve students’ digital literacy. For example, a brief five-minute lecture introduction to online reference generators, while not ideal for teaching proper referencing, offers a practical way to reduce unattributed work in the assessments. Similarly, instead of simply marking down for poor grammar and spelling, I demonstrate how students can ethically use AI tools or Word’s Editor to identify and correct writing errors. This improves submissions and, more importantly, helps students recognise their own mistakes, something assessment feedback alone can’t always achieve. These small adjustments reinforce the importance of integrating practical, accessible, and empowering digital skills into the curriculum.

To address specific digital literacy gaps in relation to quantitative research methods that I teach, I create video tutorials or dedicate class time to demonstrating essential skills, tailoring instruction to student needs and module context. I supplement this by incorporating existing resources—library guides, IT support pages, academic misconduct policies—directly into the module’s Moodle page for easy access and increased engagement. However, simply providing links isn’t enough; many students need more structured support, such as platform-specific tutorials (e.g., Windows and iOS versions). To improve accessibility and promote collaboration, I’m developing my video tutorials into open educational resources. Finally, a bank of task-specific tutorials, organised by function (e.g., using SPSS), is available on the module’s Moodle page for easy reference.

As Seargeant & Tagg (2018) rightly emphasise, navigating online information is a learned skill, not an innate ability. Education plays a vital role in raising awareness of how information flows and influences engagement with opinions and values, including understanding the interplay of opinion and fact in online sources and how the creators’ aims influence this balance (Seargeant & Tagg, 2018). Finally, digital inclusion is complex. Micklethwaite (2018) points out that digital exclusion can be difficult to identify, as even frequent social media users may lack access to or confidence with other essential digital tools. Barriers to digital inclusion can stem from various factors, including financial constraints, lack of access to reliable internet connectivity, disabilities, and cultural or linguistic backgrounds. Furthermore, digital inclusion is not linear; individuals move in and out of engagement as they develop and refine their skills. As educators, we must recognise these barriers and create a supportive environment for all students to develop their digital competencies.

While the responsibility for addressing digital literacy gaps often falls on educators, it is important to acknowledge the crucial role of institutions in providing comprehensive support. This includes offering professional development opportunities and integrating digital skills training into the curriculum. As Secker (2018) suggests, if a digital literacy framework does not exist, universities should consider creating one, either across the institution or tailored to specific schools/departments, using perhaps the JISC (2024) model of digital capabilities as guidance.

Conclusion

While many of the practices I now use to support students’ digital literacies were developed organically through teaching over the past four years, the EDM122 module provided a structured lens through which to understand and enhance these efforts. Prior to the module, I had not engaged deeply with the literature on digital literacy, although my experiences had already highlighted its importance. Exposure to key readings, particularly Radovanovic (2024), Bennet and Folley (2018), and Secker (2018), encouraged me to reflect more critically on my assumptions and inspired new approaches. For example, I now plan to incorporate scaffolded digital literacy checkpoints into each module—short, embedded tasks that progressively develop students’ capabilities, from academic communication to data evaluation. I am also exploring ways to co-create digital learning resources with students, supporting both digital production skills and a greater sense of ownership over their learning.

My experiences have shaped my understanding of what it means to be an educator. It’s not simply about teaching content, but meeting students where they are and fostering their digital competence. As digital literacy evolves with technology, so too must our approaches. Like Radovanovic (2024), I believe future curricula must integrate these developments to equip students for a digital and data-driven workforce, empowering them to understand, navigate, create, and collaborate within the digital world of AI, augmented reality, robotics, algorithms, and virtual platforms. While moments of frustration or surprise are inevitable, I now see these moments as valuable growth opportunities for both my students and me as an educator.

This reflection on my journey as an educator aligns with Kolb’s Experiential Learning Cycle (1984), progressing through its four stages: concrete experience (observing students’ digital struggles), reflective observation (questioning my assumptions), abstract conceptualization (understanding digital literacy’s complexities), and active experimentation (implementing interventions). This cyclical process has shaped my teaching and fostered students’ digital competence.

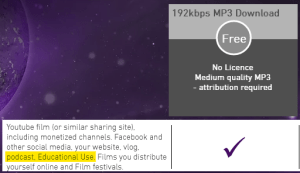

This essay is published under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license, enabling open sharing while ensuring proper attribution. It grants the right to copy, distribute, modify, and adapt the material, including for commercial use, as long as the original author is credited and allows re-licensing of derivative works.

References

Akcayir, M., Dundar, H. and Akcayir, G. (2016). What makes you a digital native? Is it enough to be born after 1980? Computers in Human Behaviour, 60, pp.435–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.089.

Bashir, A., Bashir, S., Rana, K., Lambert, P. and Vernallis, A. (2021). Post-COVID-19 Adaptations; the Shifts Towards Online Learning, Hybrid Course Delivery and the Implications for Biosciences Courses in the Higher Education Setting. Frontiers in Education, [online] 6(1). https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.711619.

Bennet, L. and Folley, S. (2018). D4 curriculum design workshops: a model for developing digital literacy in practice. In: K. Reedy and J. Parker, eds., Digital Literacy Unpacked. [online] Cambridge University Press, pp.111–121. Available at: https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783301997.

Bennett, S., Maton, K. and Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39(5), pp.775–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00793.x.

Burton, L.J., Summers, J., Lawrence, J., Noble, K. and Gibbings, P. (2015). Digital Literacy in Higher Education: The Rhetoric and the Reality. In: Myths in Education, Learning and Teaching. Palgrave Macmillan London, pp.151–172. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137476982_9.

Creighton, T.B. (2018). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants, Digital Learners: An International Empirical Integrative Review of the Literature. Education Leadership Review, 19(1), pp.132–140.

Garcia, E., Dungay, K., Elbeltagi, I. and Gilmour, N. (2013). An Evaluation of The Impact of Academic Staff Digital Literacy on The Use of Technology: A Case Study of UK Higher Education. In: EDULEARN13 Proceedings. pp.2042–2051.

Guo, R.X., Dobson, T. and Petrina, S. (2008). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants: An Analysis of Age and ICT Competency in Teacher Education. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 38(3), pp.235–254. https://doi.org/10.2190/ec.38.3.a.

Jisc (2024). Individual digital capabilities. [online] JISC. Available at: https://digitalcapability.jisc.ac.uk/what-is-digital-capability/individual-digital-capabilities/ [Accessed 5 Feb. 2025].

Kincl, T. and Strach, P. (2021). Born digital: Is there going to be a new culture of digital natives? Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science, 31(1), pp.30–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/21639159.2020.1808811.

Kirschner, P.A. and De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67(67), pp.135–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.001.

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 8(4).

Levy, L. A. (2018). 11 Digital Literacy Myths, Debunked. Available at:

https://rossieronline.usc.edu/blog/digital-literacy-myths [Accessed 25 Jan. 2025].

Micklethwaite, A. (2018). Onwards! Why the movement for digital inclusion has never been more important. In: K. Reedy and J. Parker, eds., Digital Literacy Unpacked. [online] Cambridge University Press, pp.191–201. Available at: https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783301997.

Murray, M.C. and Perez, J. (2014). Unravelling the Digital Literacy Paradox: How Higher Education Fails at the Fourth Literacy. Issues in Informing Science and Information Technology, 11, pp.85-100. https://doi.org/10.28945/1982.

Nicholls, J. (2018). Unpacking digital literacy: the potential contribution of central services to enabling the development of staff and student digital literacies. In: K. Reedy and J. Parker, eds., Digital Literacy Unpacked. [online] Cambridge University Press, pp.17–28. Available at: https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783301997.

Pangrazio, L., Godhe, A.-L. and Ledesma, A.G.L. (2020). What Is Digital literacy? a Comparative Review of Publications across Three Language Contexts. E-Learning and Digital Media, 17(6), pp.442–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042753020946291.

Passey, D., Shonfeld, M., Appleby, L., Judge, M., Saito, T. and Smits, A. (2018). Digital Agency: Empowering Equity in and through Education. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 23(3), pp.425–439. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-018-9384-x .

Pentaris, P., Hanna, S. and North, G. (2021). Digital poverty in social work education during COVID-19. Advances in Social Work, 20(3), pp.x–xii. https://doi.org/10.18060/24859.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, [online] 9(5), pp.1–6. Available at: https://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf [Accessed 5 Feb. 2025].

Radovanovic, D. (2024). Digital Literacy and Inclusion. 1st ed. Springer Cham.

Radovanovic, D., Hogan, B. and Lalic, D. (2015). Overcoming digital divides in higher education: Digital literacy beyond Facebook. New Media & Society, 17(10), pp.1733–1749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815588323.

Riordan, M.A., Kreuz, R.J. and Blair, A.N. (2018). The digital divide: conveying subtlety in online communication. Journal of Computers in Education, 5(1), pp.49–66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-018-0100-6.

Ruediger, D., Cooper, D.M., Bardeen, A., Baum, L., Ben-Gad, S., Bennett, S., Berger, K., Bonella, L., Brazell, R. … & Yatcilla, J. (2022). Fostering Data Literacy Teaching with Quantitative Data in the Social Sciences. [online] Ithaka S+R. Available at: https://sr.ithaka.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/SR-Report-Fostering-Data-Literacy-092722.pdf [Accessed 5 Feb. 2025].

Russo, K. and Emtage, N. (2024). The Digital Divide and Higher Education. In: Digital Literacy and Inclusion. Springer Cham, pp.81–97.

Seargeant, P. and Tagg, C. (2018). Critical digital literacy education in the ‘fake news’ era. In: K. Reedy and J. Parker, eds., Digital Literacy Unpacked. [online] Cambridge University Press, pp.179–189. Available at: https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783301997.

Secker, J. (2018). The Trouble with Terminology: Rehabilitating and Rethinking ‘Digital Literacy’. In: K. Reedy and J. Parker, eds., Digital Literacy Unpacked. [online] Cambridge University Press, pp.3–16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.29085/9781783301997.

Selwyn, N. (2009). The digital native – myth and reality. Aslib Proceedings, 61(4), pp.364–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/00012530910973776.

Summers, R., Higson, H. and Moores, E. (2022). The impact of disadvantage on higher education engagement during different delivery modes: a pre- versus peri-pandemic comparison of learning analytics data. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 48(1), pp.1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2021.2024793.