On 23rd May 2014, during my second, unplanned visit to the Comics Unmasked exhibition at the British Library, I happened upon the very talented Mr Woodrow Phoenix getting ready to give a live presentation of his monster-sized work, She Lives. I had no idea these ‘short’ talks were going on, so the whole thing was doubly serendipitous. All the more so for the fact that what I was treated to was an amazingly tactile and visceral experience.

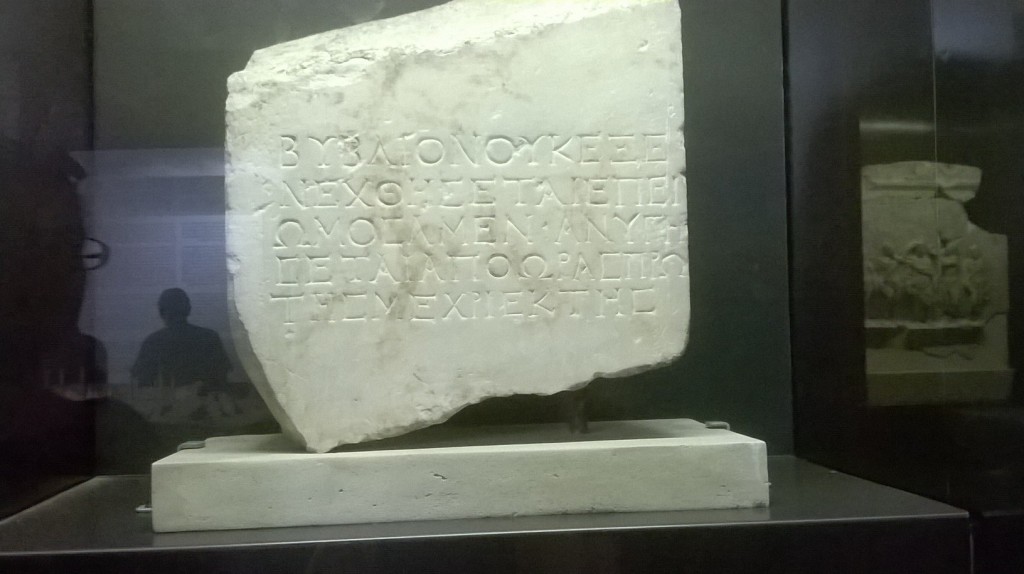

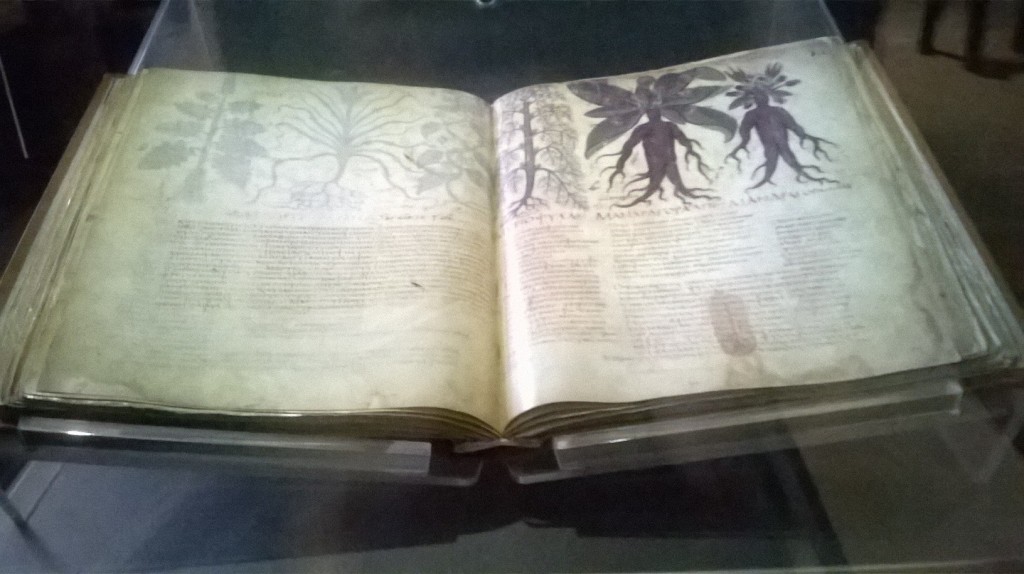

Being at the front helped. It meant I was one of the few in the audience that had the distinct privilege of helping to turn the pages, to feel the handmade, embossed cover, to run my fingers over the smooth, shiny expanses of black ink and the knobbly ridges of corrector fluid. All too often reading comics involves solely visual ingestion of the material – you pick up the comic, you open it, you look at it, read it – its pages are either smooth and glossy or matt and slightly rough – as a printed artefact it is uniformly homogeneous, a processed piece of finished product wherein the story of its production is, if you will, a closed book. She Lives reminds us – like the illuminated manuscripts that preceded the printing press – that comic books have a double life: on the one hand, a life as a commodity; on the other, a life as a work of art. It is all the more interesting that Phoenix does not plan to print the book – in an industry that is known (whether rightly or wrongly) to churn out the throw-away and the ephemeral, She Lives will remain a one-of-a-kind, a real work of art – an artefact that refuses to suffer from the losses of reproduction.

What is also apparent with She Lives is the vast amount of real blood, sweat and tears that went into its making. It’s physical size is staggering (it’s just under a square metre, it’s width double that when opened). When you consider that it was hand-bound, embossed, and went through at least 3 previous iterations (as dummy books), the work involved in its creation is all the more impressive. Stitching together such a large book was a feat in itself (involving much self-puncturing with the needle); and none of the repetitive sequences (totalling about 60 individual panels in a single round) are mechanically reproduced. All are hand-drawn. Ink spillages (of which a few were substantial) were painstakingly whited out. The physical processes involved in bookbinding and embossing demanded much research. So too did the environments and acts of a 1940’s circus and its performers, which make up the setting of She Lives.

Seeing the comic in its display case is impressive in itself. But having the chance to read it is something else. There is no narrative text, no captions or speech bubbles – yet still there is a sense that it is read. Phoenix’s talk-through focuses mainly on the making-of the piece, which does not interrupt the flow of that reading, but instead augments it with a sense of wonder that such an endeavour was possible at all. The sheer size of it demands a more leisurely pace in the reading of it, and this affords the chance to appreciate the artistic details of the comic. Turning the large, heavy pages makes the reading a tactile experience, a communing with a piece of art that made me wonder what it must have felt like for the kings, princes and nobles of yesteryear to leaf through their priceless manuscripts.

This act of reading was carefully crafted by Phoenix himself. As a document, She Lives plays with concepts of reading a book or comic when there are no words to read. The physical size and weightiness were intentional experiments in resolving this question, as Phoenix explains:

Because silent comics can paradoxically be very difficult for readers to engage with (many people interpret a silent panel as having no important story content) a comics creator must make readers understand that the pictures do not just support the captions and speech balloons but contain and deliver as much or more information in their own right.

Back in 2002, Marvel tried a silent comic campaign with their ‘Nuff Said event. My enduring impression of the event was how confusing some sequences were – how you sometimes really had to think what on earth was going on. She Lives doesn’t suffer from that. There is an elegant flow to the panels and action, no doubt thanks to the meticulous thought, effort and time that went into its making (time that the Marvel guys probably didn’t have the luxury of). Size and weight prove to be brilliant strategies in pacing the reader, in guiding their journey through the book. “In order to hold the reader’s attention,” Phoenix says, “and to direct their gaze, my strategy was to present them with a large surface and heavy paper that would have the effect of slowing the reader down and making them stay on the page longer, to look more closely at what the page contains.” It was clear, from the reactions of those at the page-turning event, that the strategy also increased readers’ sense of immersion and wonder.

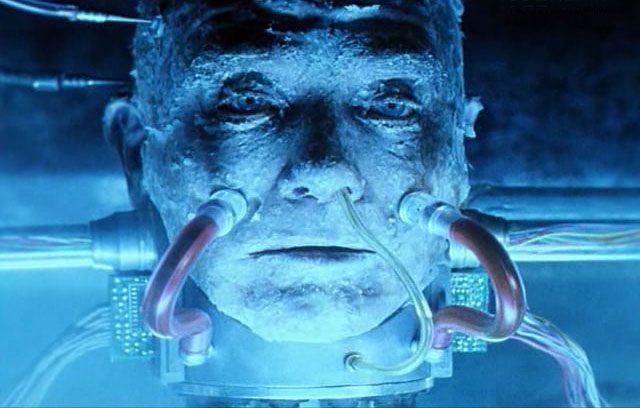

On a more personal level, what struck me about She Lives is that it is a fan work. I’m aware that the term has derogatory connotations attached to it; words such as derivative and even intertextual, which have been applied to concepts of fan work, imply a somehow subordinate role to the original material that a fan work may be based on (Derecho, 2006). The point is that She Lives proves that such works can be both original and of high quality. Set in the late 1940’s, it takes up the story of the Bride of Frankenstein, giving one of those continuations of a closed off plot that fans so enjoy playing with (Bacon-Smith, 1992; Derecho, 2006; Jenkins, 2013 [1992]). Everything about the comic – from the lavish attention to detail, to the sense of motion in its panels, to its visceral physicality – pays testament to the love Phoenix has for his subject matter, to his desire to explore beyond the boundaries the 1935 movie presents.

Nevertheless, it is interesting that Phoenix himself does not see his piece as fan work, or even as a tribute. “This story was inspired by the ending of Bride of Frankenstein, but I don’t think of it as a fan tribute,” he says in an email conversation with me. “It’s more like I’m using something that was discarded. The titular character only appears in the film for two minutes and she dies without speaking, having barely done anything… There’s nothing to her as a character apart from a fabulous visual design.” And, according to Phoenix, it was that visual design that prompted him to continue her story:

I would occasionally wonder about what could have happened with her had she lived. And then one day an image occurred to me of her sitting in the dark smoking a cigarette. I thought it might make a good short story: the bride of Frankenstein had survived the explosion but had no function, no purpose or place to be, and was living in a trailer or a motel somewhere in Glendale, California.

This thought led him to the backdrop of She Lives – to “the idea [of] a freak or outcast who hides amongst other freaks”. The circus seemed to be a natural extension of that; and once the idea had started rolling, the Bride character was no longer strictly needed. Nevertheless, Phoenix kept her as a sort of ‘anchor’ for the reader, not simply as a striking visual motif, but as an “extra resonance” to those who would recognise who she was. To other viewers or fans of The Bride of Frankenstein, the story would be enriched, as the Bride brings with her a cultural and narrative baggage that adds a dimension to her character (and the story) that a non-viewer or non-fan might be bereft of. Her presence is not necessary, but for those in the know it provides a powerful story in its own right.

Even though Phoenix doesn’t self-identify as a fan artist per se, She Lives encapsulates several of the aspects that drive fans to create – the closed or unfulfilled plot that is rich for further development; the attraction to a certain character; the persistence of an image, plot point, or character trait that demands further exploration (Derecho, 2006).

As a piece of art, She Lives is an immensely satisfying work, beautiful, tactile, absorbing. As a comic, it is compelling, perfectly paced, painstakingly plotted, wonderful to look at. As a fan work, it is one of the best examples, even if Woodrow Phoenix did not intend it to be so. As a fan of the original film, one must certainly feel a thrill when such an iconic and beloved character reveals herself and demonstrates a continuing life beyond the four walls of the movie that once enmeshed her.

And that is what fan works are really all about – feeling a character, and bringing that character once more to life.

* Future She Lives page-turning events with artist Woodrow Phoenix take place on Tuesday 22nd July 2014 at 6pm, and Tuesday 12th August at 3pm, at the British Library’s Comics Unmasked exhibition.

References

- Bacon-Smith, C. (1992). Enterprising women : television fandom and the creation of popular myth. Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Derecho, A. (2006). Archontic literature: a definition, a history, and several theories of fan fiction. In: Hellekson, K., & Busse, K., ed. 2006. Fan fiction and fan communities in the age of the internet. Jefferson, North Carolina; London: McFarland. Ch 1.

- Jenkins, H. (2013), updated 20th anniversary ed. Textual poachers : television fans and participatory culture. New York : Routledge.