Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

One of the gems of our rare books collection is a complete copy of Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire which was published in 1789.

It’s a six volume work. Each volume is split in two making twelve books in total. The complete work covers the story of the Roman Empire from the second century CE (the time when Gladiator was set) to the fifteenth century. It’s not just a history of the Roman Empire but the history of much of Europe, Africa and Asia during this long period.

The first volume was published in 1776, the same year when the United States of America declared Independence. The final volume was published in 1788 (the year before the French Revolution). This was a time of both great change and disruption, but also continuation and tradition.

This period is sometimes called the Enlightenment. During this time scholars around the world (especially in intellectual centres like Birmingham, Edinburgh, Paris, London and Boston) wrote books and articles which challenged previous ways of thinking. Gibbon was part of this movement. He believed that the fall of the Roman Empire was caused by, and caused, the growth of medievalism. He thought this was a bad thing and that the Roman Empire was a good thing. The Roman Empire was built on colonialism and slavery and saw massive inequality.

Decline and Fall is both an epic work and a piece of sustained scholarship, however it is of its time. Some of Gibbon’s conclusions are not necessarily followed today, but he is still praised for a fine and vigorous prose style.

The state of scholarship

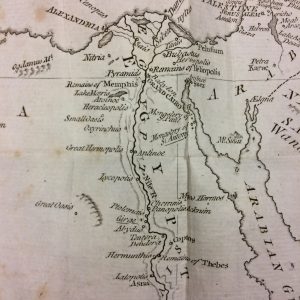

This map shows the relative knowledge of Italy and Egypt. Italy was a stopping point on the infamous Great Tour and many rich Britons would have visited it. Very few Europeans had traveled to Egypt at the time Gibbon was writing his work. Now a days a lot more is known about Egypt, almost more than Italy or Greece, due to discovery of extensive papyrus records.

The author

Gibbon was briefly an MP in parliament but his greatest achievement was this history. He was noted for the critical use of primary sources and was a great example of the value and importance of a solid underpinning of information literacy.

He was also a very well traveled man and a part of that great European Republic of Letters which has survived even to this day in places like City, University of London which value and support the importance of internationalism.

For many people, perhaps, Gibbon’s legacy can be summed up in the apocryphal words of King George III ”Another damned big black book, Mr. Gibbon. Scribble, scribble, scribble – eh, Mr. Gibbon?” It’s certainly a big book, bigger than anything by Tolstoi, but just as readable.

In the 240 odd years since its publication, even though few have read it and the world has changed, many of Gibbon’s presumptions and ideas have become commonplace. Returning to the beginning and learning good information literacy, we can learn to challenge many of these ideas and begin to write our own histories.