Following on from the invitation circulated by ALISS, we joined a small group of fellow professionals in an area currently buzzing with projects in the Library and Archive world. The visit was to introduce us to the archive and exhibitions of the Garden Museum, recently renovated during an £8,000,000 development project (2015-2017), and holding a growing archive collection. The Museum is located next to Lambeth Palace, where a major building project is currently underway, to create a brand new Library.

This vibrant area is also a good place to learn about London past. The Garden Museum itself was developed in a church, St Mary-at-Lambeth, which is first mentioned in 1086 in the Domesday Book but actually predates the Norman Conquest. The church was rebuilt in stone in 1337, and the tower from this time remains today. The body of the church was rebuilt again in 1851. The Museum was founded in 1977 by a local resident who wanted to rescue the abandoned church due for demolition. The site is particularly apt, as St Mary-at-Lambeth is the burial place of the first great British gardener and plant-hunter, John Tradescant (c1570 – 1638), who founded Britain’s first public museum in around 1629, hence the Museum’s mission to ‘explore and celebrate British gardens and gardening’.

The recent redevelopment project created modern spaces inside the church and churchyard while preserving the site’s historical features. They were put together using a prefabricated, cross-laminated timber technology developed in Switzerland, which made it possible not to dig foundations or fix anything into the walls of the listed building. The spaces were also designed to let as much natural light in as possible, so that the place would have a calm feeling to it, very much suited to the subject it seeks to showcase.

The Museum includes various spaces, such as an art gallery with a temporary exhibition, a series of displays on gardens and gardening, a learning centre, and of course a lovely garden café. There is also a room where visitors can admire some of the church artefacts, as well as peer into the entrance to the Archbishops’ vault. The latter is a fantastic discovery made during the recent building works. Deep underneath the chancel of the church, 30 people of high standing, including up to five Archbishops of Canterbury, had been buried… and forgotten! The entrance to the vault, leading directly to a steep staircase, can be seen in the middle of the floor.

Not far from this room, a digital display board enable visitors to explore further the local history, by following the footsteps of former Lambeth residents, such as Charlie Chaplin or William Blake.

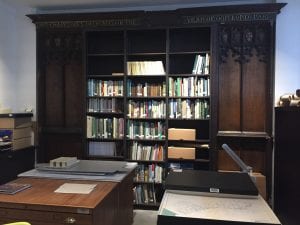

The archive is housed in two purpose-built rooms, on the ground and second floors of the new structure, occupying a space that used to be one of the church side chapels. A few stairs as well as a carved wooden screen lead visitors to the door. The latter, as it is transparent, let them see the Victorian altarpiece still standing against the back wall and repurposed as a bookcase. The two climate-controlled rooms house racking for boxed items on the upper level, and plan chests and a small reading room on the lower level. The archive also has a freezer for storing photo slides and for disaster preparedness (the first step in the case of water ingress in an archive is often to freeze items until the damage can be properly treated), although the freezer is currently employed as a wine fridge.

The current archivist, Gillian Butler, had however spared no effort to make our visit worthwhile and had gathered in the ground floor room some of the highlights of the collection she is responsible for. The archive’s remit is contemporary garden design and business, from the early 20th century to the present day – a survey found that older designs are generally well-documented in local and national archives. Few of the collections are currently catalogued, although the work of Russell Page (‘the most famous garden designer no one’s ever heard of’) was catalogued as part of a recent project.

The Page collection is representative of the items the archive collects: garden designs on largescale drafting paper, business records, and personal items from the designer’s life (including scrapbooks and the pencils he used to draft his designs). There were also slides of gardens by Andrew Lawson, a leading garden photographer, which are actually the only slides surviving from a bigger collection predating the digital era that he unfortunately cut down at some point. The archive contains numerous personal items from leading gardeners, including the diaries of plantswoman Beth Chatto. Most interestingly, we were also told about a living collection held by the Museum. The working papers of John Brookes, an influential garden designer who died in March earlier this year, were deposited at the Museum. But they are still very much in use by the people who are now carrying on his business, which results in plans being often taken back!

Works are largely on paper, and can be stored flat, rolled, or folded. Some collections from specific projects are stored in all three ways, and therefore are stored in three different sections of the archive. The archive can accept some digital design files converted to PDF format, although does not currently have capacity to hold original CAD files used by many contemporary designers.

Collections are currently built largely on word-of-mouth, using the well-connected nature of the gardening world. Because of this, the archive also sees a high research demand, and is currently trying to focus on answering queries remotely because of limited space and opening hours to handle the level of demand, and because much of the archive’s business and personal contents is still privileged under the Data Protection Act. Archive collections are also used as part of the museum’s displays, and rotated on a regular basis to limit their light exposure, ensuring their continuing availability for future generations.

The Garden Museum in Lambeth does have a lot on offer, much more than its name would first suggest. It can probably satisfy a variety of interests, ranging from local history to architecture, as well as gardens and gardening! And if this was not enough, the café serves every day ‘fresh and seasonal food, with a focus on simple, quality ingredients’…

Andrew Medder and Claire Audelan