For most of us, preparation for a quality audit is not the most exciting way to spend an afternoon, so last week my colleagues from Learning Success and Student Counselling and Mental Health Services decided to use compulsory pre-audit training required by the newly established Disabled Students Allowances Quality Assurance Group (DSA-QAG) as a space to reflect on our practice and service delivery. Just as well; I had the unenviable challenge of making sure we fulfilled the audit requirements of DSA-QAG training, while not teaching a dozen or so grannies (i.e. my highly experienced peers) to suck their proverbial eggs.

According to the latest statistics, over one thousand students at City have been identified as having a disability, many of who are entitled to DSA-funded specialist study skills and/or mentoring support. This blog sheds a little light on some of the work of colleagues at the forefront of this provision while under the watchful eye of DSA-QAG.

DSA changes

Following the DSA changes announced by the government in 2014, higher education providers are now expected to take on greater practical and financial responsibility for supporting students with disabilities. In addition, staff providing DSA-funded support (referred to as ‘non-medical help support workers’) must also ensure their work is compliant with the standards laid down in the DSA Quality Framework: this includes the requirement for training on disability awareness, professional boundaries and policies. The first round of quality audits began in early 2017; an extra driver for our training session was the news that City has been scheduled for audit in the next few weeks. However, we are a multidisciplinary team and work with many students who are not entitled to DSA funding, so while the ultimate goal was to be audit ready, we were clear that the need for compliance would not deny us an opportunity for learning.

Disability awareness

Like any good (aka desperate) teacher, my strategy was to sandwich the less exciting bit of the training between the good stuff and then bung in a few treats for good measure. We began with the disability awareness session which, again, might seem like overkill for experienced professionals, but the diversity of the group made for an interesting discussion.

It’s been ten years since the UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was opened for signature and activists continue to campaign for the rights of disabled people. The two key ‘models of disability’, the medical model and the social model, are typically presented as opposing philosophies, thereby leading to different interventions and outcomes in education and the workplace. Many (including most of us who work in this field) reject the way that disability is too often pathologised, focusing on what’s wrong with the individual (the ‘medical’ model), in favour of placing the focus on the way society disables people (the ‘social’ model). Even with the social model, however, much of the language we use to talk about disability is medicalised – dyslexia has to be ‘diagnosed’ before a student can apply for DSA. Further discussion supported the view that at their extremes, neither model fully reflects the complex nature of disability. Just as the wider debate continues and alternative models of disability are considered, our discussion touched briefly how a ‘biopsychosocial’ model such as the one first proposed in the 1970s by U.S. psychiatrist George Engel takes a more holistic approach to disability.

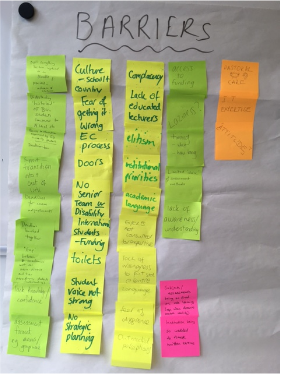

Having critiqued established models of disability, we went on to talk about the barriers to learning experienced by students with disabilities and captured them on post-it notes (see the Fig. 1). It was felt that one of the biggest barriers to success was attitude; changing attitudes at all levels in the institution would remove the need for many of the ‘reasonable adjustments’ that stigmatise students and can cause resentment among those who are unsure as to why there is a need to level the playing field. This is particularly evident when it comes to ‘hidden’ disabilities like dyspraxia, depression or diabetes.

Professional boundaries

Session two was a review of the paperwork needed for audit. I won’t bore you with the details but I can say, especially given the sensitive nature of our work, it was helpful to remind ourselves about City’s policies and procedures regarding matters including Safeguarding and Data Protection. After this, we moved onto our final session on professional boundaries. Phew.

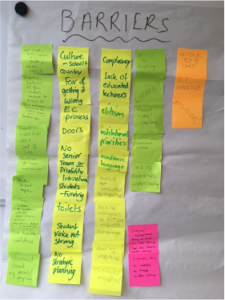

Working one-to-one, often with ‘vulnerable’ students, has the potential to cross various boundaries which could have serious implications for both parties. Fig. 2. shows the boundary topic clues we used as a fun way (come on, it was audit training after all) to kick start the conversation. Can you work out what each one stands for?*

A fascinating discussion then ensued: how, for example, does one politely refuse an expensive gift from a grateful student without causing offence? Is it acceptable to respond to emails outside of work hours? What should one do when a student (who attributes your support to their achievement) leans in for a hug? These and other ‘red flag’ situations were shared then ‘tested’ against guidelines laid down by our respective professional bodies.

And before we knew it the training was over – not so bad after all. It wasn’t just about ticking a box (although this was needed), we created a space to reflect on what it is that we do and linked this to the bigger challenge of embedding high quality inclusive practice across the university. What I took away was a sense of the ongoing commitment to work (both in our individual teams and as part of LEaD) with colleagues in the wider institution, by sharing examples of good practice and offering specialist guidance where needed. If that’s the evidence the auditors are looking for, we have nothing to fear.

Would your department benefit from Disability Awareness training? Why not have look at the Learning Success and Student Counselling and Mental Health webpages or get in touch to learn more about our services.

Jannett Morgan is a Neurodiversity Support Tutor in Learning Success@ LEaD. If you have any questions regarding this blog or are interested in Disability Awareness training, please contact Jannett.Morgan.1@city.ac.uk

*Still trying to work out those clues? Professional boundaries items from top left then clockwise: mini roll=job role (geddit?); boxing glove=touch; egg timer=time; shoe=clothing, boxed gift=gifts; torch=disclosure; Jamaican dollar bill=money; monopoly hotel=place and space

References

Engel GL. The Need for a New Medical Model: A Challenge for Biomedicine. Science, New Series, Vol. 196, No. 4286 (Apr. 8, 1977), pp. 129-136. Available at http://www.jstor.org/stable/1743658 [Accessed: 24-05-2017].

DSA-Quality Assurance Group. Non-medical Helper Providers: Quality Assurance Framework. February 2017 Version 1.4. Available at https://www.dsa-qag.org.uk/application/files/6414/8647/5954/NMH_Quality_Assurance_Framework_V1.4.pdf [Accessed 10.05.17].

Shakespeare, T. 2014. Disability Rights and Wrongs Revisited. 2nd edition. Oxon: Routledge.