The post below is a transcript of a closing keynote I gave at a UK Council for Graduate Education (UKCGE) workshop in November 2019. It contains three case studies of how LEaD have worked with City academics on educational development or enhancement activities. I’ve published it here to add to LEaD’s new Case Studies archive, but also to share these three examples with the wider City community.

The post looks at how an assessment on LEaD’s MA in Academic Practice was changed from an individual essay to a collaborative group assignment, at how a mobile voting system was introduced to barrister training in the City Law School, and how we worked with the Department of Computer Science and others in Professional Services to develop a lab for teaching a new Masters in Artificial Intelligence. It was a 20 minute talk, so makes for a long read!

Given how the pandemic has upended everything, these might seem stories from the ancient past. Hopefully though, there should be plenty of useful lessons that can also be drawn in terms of how LEaD can work with staff to develop their online practice, or for once there is a return to campus.

I also joined the UKCGE for a webinar in April on ‘Adapting Postgraduate Education for Remote Delivery‘. Many thanks to all involved in the case study examples below.

Good afternoon. I’m Dom Pates, and I’m a Senior Educational Technologist at City, University of London. I was delighted to be asked to speak at this event by Jorge, with whom I began my journey into technology-enhanced learning within Higher Education. It’s an honour to be able to give this event’s closing talk, to continue this journey with other current or former colleagues — nods here to Santanu and Leonard — and to have the opportunity to share a few stories with you assembled here in this room today. I hope that these stories give you something interesting to think about, and something useful or practical to take away back to your own workplaces.

I work in the Department for Learning Enhancement and Development, or LEaD for short, and I manage the ed tech relationship between our department and three of City’s schools — Cass Business School, the City Law School, and the School of Mathematics, Computer Science and Engineering. That’s more than enough on my workload plate to keep keep me on my toes most of the time!

Educational or Learning Technologists are renowned within our own communities for endlessly ruminating over what it is that we actually do. This is partly because it’s quite a tricky role to easily define. We often sit in the grey zones between more clearly defined areas of work within our institutions. I have both a teaching background and have worked within a large, overstretched IT Services department, and this means that I have enough of an immersion in both worlds — the educational and the technical — to speak both languages. Nevertheless, this linguistic flexibility is not always easily understood by either stakeholder. I recently received a complaint from one of our staff about a password change requirement, suggesting that the change was ‘to give you guys something to do’. I had to let him know that I was just as irked by the change as he was, and that it had nothing to do with me!

I’ve found the simplest way to explain what I do to those outside of Technology-Enhanced Learning circles is to tell people that I ‘help academics to use digital technologies in their teaching’. At City, that extends to contributing to the design of learning spaces too. As you might imagine, helping academics use digital technologies in their teaching and contributing to the design of learning spaces is a rather large umbrella that covers a vast array of activities and perspectives, particularly when applied across the three schools or to the wider institution that I work with.

Today, I’ll be sharing three of those stories with you. I’ll be fitting in a little interaction too, so it’s not just me talking the whole time, and I’ll leave some space for questions at the end. But before I start with the first story, I’d like to tell you a little about my own experiences as a postgraduate student. I’ve found that in order to succeed amidst the complexity of my role, it’s often necessary to consult widely in order to gather a plurality of perspectives. Students are one of the key stakeholder communities in higher education, so it’s imperative to include their voice in educational development initiatives. So first up, this is my own student voice.

About eight years ago, I started a Masters degree in Digital Media at the University of Sussex. I was working full time in a demanding job and already had a postgraduate teaching certificate under my belt. I was looking for my scholarly endeavours to afford a chance to return to the humanities seam I’d been exploring as an undergraduate in the 1990s, but to update my perspectives for the new digital age. As a highly enthusiastic user of digital technologies that had begun to incorporate them into my own teaching, I’d nevertheless felt the need for more of a counter-balance to my perspectives. I was also looking for an opportunity to extend my practical skills with using digital media tools and with authoring content. These motivations were underpinned by my understanding that this was something that I needed to do in order to advance my career to the next level.

What I later came to understand as technology-enhanced learning was the thread that ran through most of this study. I looked at areas such as the use of Twitter as a backchannel at academic conferences, the impact of teachers’ lack of physical presence in digitally- networked learning environments such as webinars or MOOCS, and how to run learner- centred design projects. The most profound aspects of the programme, that I carried over into my later work in higher education were some of the practices and approaches I experienced on the programme. These included being able to use video as an essay medium, the balance struck between theoretical and practical application, assessed group- based project work where we were able to define our own roles within the groups that formed, and the ability to take modules in other schools that were outside my chosen pathway.

Although as a busy professional, I was unable to take advantage of some of the social and extra-curricular opportunities that a campus-based Masters programme offered, the practices and approaches of the programme stretched me, gave me the flexibility that I sought, and highlighted approaches that would provide later inspiration in my career path that was to follow. The group assignment was to provide some of the inspiration behind the first case study that I’m going to talk about today.

…

LEaD run a Masters in Academic Practice, which is a postgraduate taught programme that is aimed at staff in Higher Education for developing their teaching skills and educational knowledge. Starting in 2016, Santanu and I took over teaching a small part of one of the programme’s modules, which focused on the role that digital technologies can play in student support and personal tutoring. We initially reshaped that taught session from being a presentation-heavy part of the module to one that was far more geared towards group discussion activities and peer learning. We felt that our learners would get more out of a focus on tools and technologies if they were able to investigate the issues and explore them with colleagues rather than from just taking notes in another slide-driven talk. We also wanted to demonstrate effective pedagogical practice as part of our approach.

As can often happen in HE, module leadership was to change hands a couple of times. I tend to see periods of change as moments of opportunity, and so opened a conversation with the first new module leader about the module’s assessment, which had been one of several essay assignments deployed on the programme. Assessments, of course, are where the educational stakes are highest, both for learners and for a module team, and can therefore be among the more difficult components of a module to change. However, I had a hunch for a new approach to the module assessment that drew on an idea from a conference I’d attended earlier in the year, my experience on my own MA of a group assignment, and a taste for continuing to bring something new to the module, following the rewriting of the taught aspects.

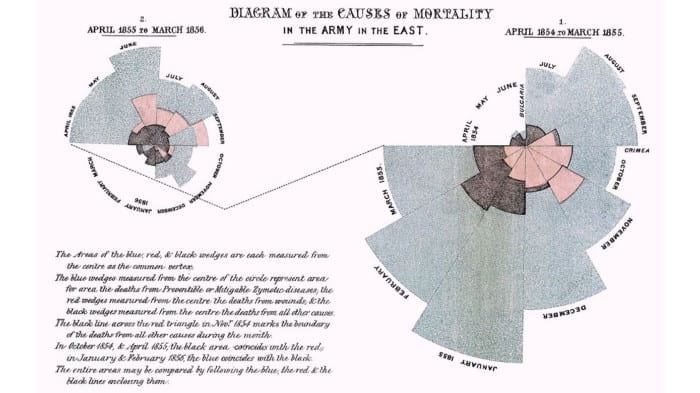

At an HEA conference on teaching STEM subjects, one of the presenters had spoken about her experiences of using student-created infographics in Chemistry assignments. For the unfamiliar, infographics are visual representations of information, data or knowledge, deployed for presenting information clearly and quickly, and for making it easier for people to see patterns and trends in the presented data. The techniques for graphical displays of information have been in use for some time. Florence Nightingale’s 1857 diagram to illustrate the main causes of mortality in the Crimean War was used to persuade Queen Victoria to improve conditions in military hospitals. Public transportation maps such as that of the London Underground are another well-known example of infographics. However, while the graphical display of information might have been in use for some time, I would argue that it is with the growth of networked digital media and the rise of the field of data visualisation that infographics have gained greater currency in the public imagination.

Having an ability to condense quantitative amounts of information into easily understood visual displays could be seen as an important contemporary professional skill. Bringing infographic creation into teacher education was therefore one way to incorporate digital capability development into one particular postgraduate curriculum. It took the arrival of a second new module leader — Dr Ruth Windscheffel — for a proposed change in assessment method to move more fully from idea to implementation, and change it did.

Introduced in academic year 2017/18, students were asked to work in discipline-aligned groups to produce and design an infographic poster using an authoring tool called Venngage, on a jointly-agreed aspect of student support and/or personal tutoring and which was aimed at informing others in their contexts. This meant that the work was to be co-created, and it was designed to be printed out and displayed.

It’s important here to distinguish between a poster designed as an infographic and a more commonly found academic poster. The conventions around academic posters mean that these are artefacts typically designed for conferences, as distillations of research, and often require somebody to stand by them to explain them in greater detail to interested parties. These can also be seen as informationally dense, and in some cases, may lack a certain design aesthetic. The infographic posters that this assignment was proposing were intended to be displayed, seen and easily understood, and could therefore be a form of authentic assessment that could be repurposed beyond the confines of the course.

There were two key rationale for introducing these changes — to bring a little more variety to assessments on the programme, and to give participants some hands-on experience of participating in group work. This assessment was intended to replace a 3,000 word essay, and the design of the assessment criteria was key to the adoption of this method. Assessors were not looking for the task to judge an individual’s capabilities as a designer, but of the group as teachers and as presenters of information. 50% of the final grade was to be a group mark, and individuals were then to submit a 1,000 word reflective report on aspects like the group’s choices and their own contributions for the other 50%. Aspects such as presentational design and poster layout were limited to just 20% of the overall mark.

Davies (2009) suggests that group work is notoriously difficult for students to engage in and for staff to facilitate well, but it’s often listed as a key skill that employers want. Activities were amply scaffolded, in order to give sustained group activity the best chance of success and to keep a sense of momentum. This included running an online ‘icebreaker’ activity prior to students meeting face-to-face, providing taught sessions on infographics generally and Venngage specifically, providing dedicated class time for participants to work together in their groups, as well as the provision of facilitated group forums on Moodle to enable all members to keep in communication with each other outside of taught time. The scaffolding intent and respective activities can be considered as positive examples of pedagogy informing designing for technology-enhanced learning.

In leading the module, Ruth uncovered several insights into benefits, challenges and good practice in running group assignments. She described afterwards that the activity had also raised issues of inclusive practice and around assessing group work, and noted that the posters were also of a high standard. Student feedback over the two years that the assessment had run reflected both the difficulties and the gains that professionals could find from learning together in groups. One anecdotal comment that a colleague who studied on the module provided me with suggested that, for him, it was the most meaningful assignment he had undertaken on the programme. Having experienced exactly the same thing on my own MA — despite having also been through the significant challenges of a group assignment too — this was exactly the sort of impact that was hoped for. Who said teamwork was easy?

…

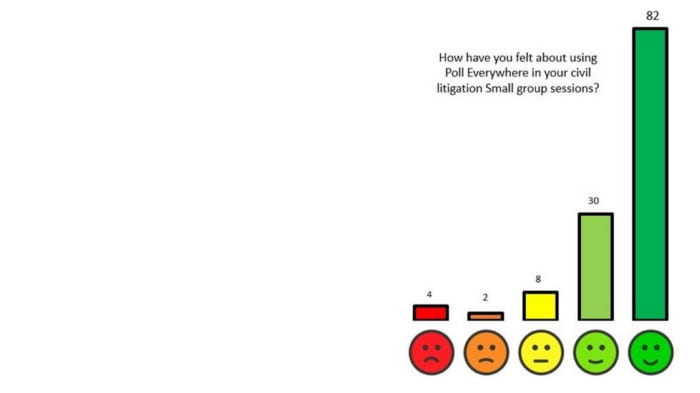

Jorge introduced me to Poll Everywhere as a student response system in my early days at City, and I’d attended a conference presentation by Snigdha Nag in my first week that recounted a Law School experiment with using it in barrister training. I liked that the tool was so easy to use, that its impact was so immediate, and that a fairly trouble-free exposure combined with a positive student experience could act as a gateway for some academics to deeper forms of technology-enhanced learning approaches. Having also used response systems in my own teaching for both enhancing the student experience and reducing my own marking workload, I was in no doubt that there was more potential to be mined with this tool. The primary factor with introducing a tool like Poll Everywhere was that it relies on virtually all learners in the room having some sort of Internet-enabled mobile device with them, which is a condition that I feel isn’t often taken enough advantage of.

The Law School’s Bar Professional Training Course (or BPTC*) is a postgraduate programme for law graduates to prepare for practising as barristers. City’s BPTC has over 300 students studying this one-year course, which includes a gruelling three hour ‘single best answer’ multiple choice exam as a key barrier to passing. Course content is divided across written, oral and knowledge subjects, with a 2,500 page hardback book providing the main textbook. Preparation for the final exam takes up a good proportion of the pedagogical focus on the course.

Could educational technologies provide a complementary way to support the teaching and student engagement on the BPTC? As Habel and Stubbs pointed out (2014), response systems are well known for encouraging student engagement and participation, even in knowledge-dense subjects such as law.

I moved into my first management role at City in the summer of 2017, with a secondment to look after our relationship with the City Law School. During this time, I was made aware of wholesale and longer term changes that were pending for the BPTC which were likely to result in a more technology-enhanced offer, and was asked for advice on the possibility of adopting Poll Everywhere for supporting student engagement in small group teaching sessions across Civil Litigation modules on that course. I also reconnected with Snigdha to see if she had any interest in reviving her earlier experiments. It occurred to me that supporting adoption of one fairly easy-to-use tool across one subject could serve as both a helpful gateway towards wider adoption of digital methods, and a good means of relationship building with a cohort of academics new to me.

Some staff on the BPTC (such as Snigdha) were already using clicker handsets to provide a little interaction in large group lectures, so there was a likely receptive audience for taking things to the next level. These handsets, however, were becoming increasingly outdated and were quite cumbersome to distribute and collect with the class sizes that the staff were contending with. Adoption of Poll Everywhere could therefore also serve as an opportunity to transition staff away from the older tools towards a newer approach. Civil Litigation module leader Veronica Lachkovic and I developed a plan for adoption across her teaching cohort, which involved discussion with the teaching staff about what it could bring to their small group sessions, staff training and printed guidance, and being on hand to troubleshoot any of the challenges they faced as they started using it in their teaching.

* Now Bar Vocational Studies (aka BVS)

Despite the challenges of integrating new teaching approaches in an intensive course, the results were noticeable. Many students liked the anonymity of being able to think about the answers without having to be identified as potentially wrong, and found it less threatening than direct questioning. Some students reported that it increased their confidence, through seeing the visual displays of others coming to similar conclusions, and they could see applications for it across the other knowledge subjects. Consistent but considered use brought more variety to the questioning methods used by teaching staff, as well as changes of pace to the sessions. Staff felt that use of Poll Everywhere provided effective practice for the exam, and that the use of the tool forced students to commit to an answer. And of course, as we all know, if you really don’t know the answer in a four-option multiple choice question, you can always guess it.

Of course, adoption of a new tool across a group of teaching staff doesn’t come without its challenges. Staff reported technical difficulties that could eat into set up time, and inconsistencies in conditions across rooms. However, these seemed to be more teething problems than insurmountable ones, and staff have now embarked on a second year of teaching the course in this way.

What implications does this case study have for pedagogy informing the way that technology-enhanced learning could be scaled? Firstly, the wider conditions were conducive for such an introduction. Older existing technologies that were used to teach parts of the course were beginning to fail, and the course itself had a ‘change paradigm’ coming anyway. Smaller scale experiments by more adventurous teachers had already been conducted. An enthusiastic module leader that was prepared to try something new was another helpful factor. These all contributed to fruitful conditions for introducing a new tool at scale.

More appropriately, perhaps, the tool fitted the teaching approach very snugly. At its simplest, Poll Everywhere is a tool that can be used for aggregating and displaying responses to multiple choice questions. This might have previously been done on the BPTC via a show of hands, secret ballots, or other methods. This tool was complementary to the way that Civil Litigation was already taught.

Having an educational technologist support the teaching team throughout the process was important too, as I could understand what they were looking to achieve pedagogically, where the tool would benefit and where it wasn’t needed, and I could act as a neutral but informed party afterwards with both staff and students when running the evaluative focus groups at the end of the first run. I could also leverage a good relationship with the vendor to ensure that their teaching needs could be as fully as possible, when I pushed at the limits of my own knowledge of the tool.

…

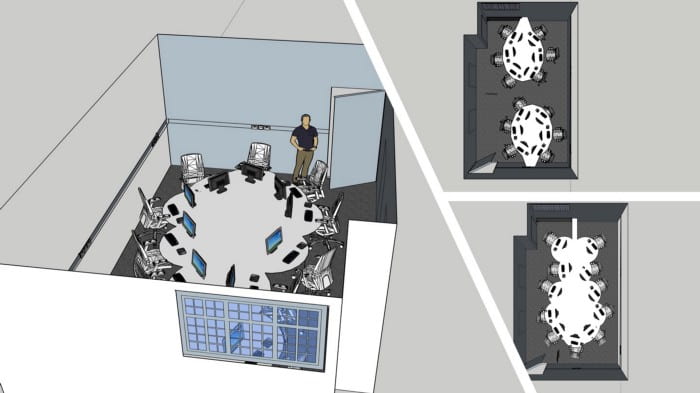

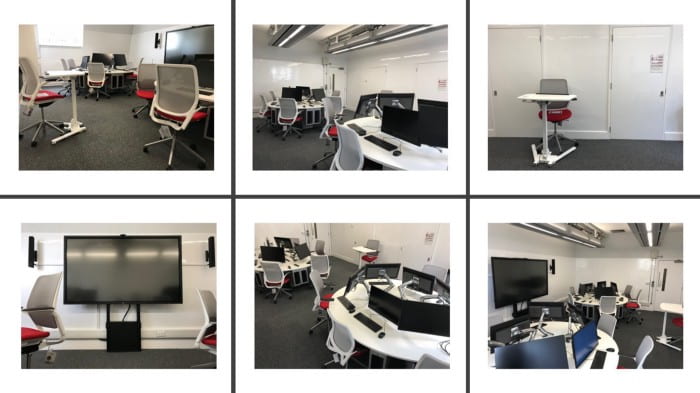

The third case study I have for you today was the first major item in my in-tray when I stepped into the current role at the end of last year. It is more of a work-in-progress than a completed case study, but there is enough of a story to tell already. City was set to launch a new Masters degree in Artificial Intelligence in September 2019, and was commissioning a new PC lab for practical sessions to be taught in. The lab was described on the website for the new MSc as a ‘world class AI Lab’ and the plans that I’d been handed consisted of rows of tables with a lectern at the front — pretty much how the Victorians might have designed an AI lab, as far as I was concerned.

But what did a world class AI lab — particularly in a space of that size — look like, and how might we draw on the intended pedagogy to help inform the design for a technology- enhanced learning space? A little initial research didn’t turn up very much in the ways of exemplars to borrow from. The lab was commissioned by Dr Eduardo Alonso, the programme director for the new MSc and the then-Head of Computer Science at City. I started off with a framework, a handful of ideas and a remit, which turned out to be not that bad a way to get started.

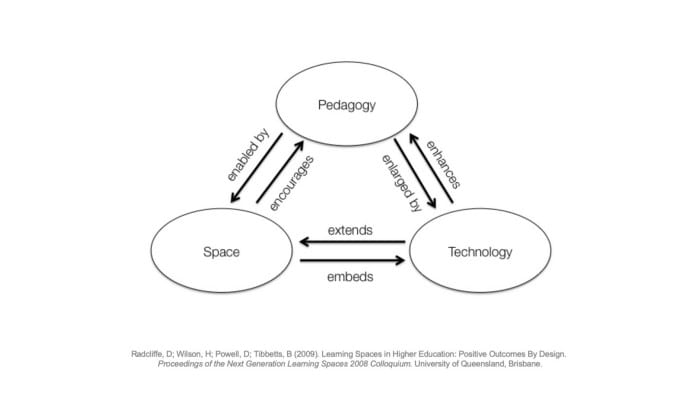

The framework is one that I have often drawn on for considering the main factors in a learning spaces project — Radcliffe et al’s ‘Pedagogy-Space-Technology’ framework (2009), which considers how these three elements equally influence each other in reciprocal ways. At its most direct, the PST framework provides for three equally-weighted categories to bear in mind when designing learning spaces. The ideas that I started with were based on my own experiences of having taught in a suite of PC labs that were each laid out in different ways — in this example, students would come together for a plenary or discussion, then head back to their own desks when they had tasks to work through, with the teacher having compete oversight of the work going on in the room. The remit, from Eduardo, was not only to respond to this ‘world class’ label as best we saw fit but also to use the room as an opportunity to explore the cutting edge in terms of in-room technologies.

I convened a working group with others from our estates, IT and AV departments, and James Rutherford, a LEaD colleague with specific expertise in designing learning spaces. The main design questions to address were how did Eduardo and his teaching staff plan to teach in there, and how did he want his students to learn. We learned from an early needs analysis that the course was intended to be hands-on and highly collaborative.

Teaching activities were to include formal lecturing using presentational material, coding demonstrations, and presentations from guest lecturers, as well as facilitated pair and group activities. Student activities were intended to be individual and group project work, software development, presentations, and coursework writing. James and I attended one of Eduardo’s classes to observe his teaching. We also dug further into the thinking behind the course itself, which Eduardo described as distinct from other Masters programmes due to its ‘nature-inspired’ focus on Deep Learning, looking at developing neural networks that replicate how the brain works.

This space, then, was to be a high-performance computing lab in a small space, that would need to support a variety of teaching and learning activities, and which would be both high- tech and themed according to the discipline. James and I worked on a variety of different design ideas for the core furniture. I’d originally wanted to put brain-shaped tables in with PCs that would sink into the surface, but space was one or our limitations and prevented this. The final designs ended up closer to speech bubbles, which also seemed fitting. We removed the idea of a teaching station completely, as Eduardo talked about teaching using a laptop. This allowed for a little more space for student seating and to deploy some of the latest wireless sharing technologies that we’d also been investigating.

We deliberated long and hard over the combination of in-room technologies balanced with writing surfaces, and visited several other locations to look at their installations. In the end, we settled on a solution powered by the Wolfvision vSolution Matrix. This facilitated both wired and wireless connections to be networked and seamlessly displayed on the main screen.

We also negotiated a solution with IT that would allow anything displayed on the main screen to also render in a browser on one of the in-room PCs. This meant that anyone in the room could share content to the main screen, which could then be pushed out to all the other PCs in the room, allowing for students to see live code side-by-side with their own workings. Instead of whiteboards, we covered the walls with writeable wall coverings, so that pretty much everywhere in the room could be used as a writing surface.

There were various features that I wanted to have installed and tested before the course launched, such as trialling different web conferencing software on the enabling infrastructure to see how well it supported remote guest speakers and in-room participants to see and talk to each other. However, time was also against us in developing this space, and we had to hand it over as the course has now started.

Still, Eduardo has also agreed to a slightly unusual approach for a learning space — we’re planning to treat it a little like software versioning. This means that version 1.0 is the launch version, when staff and students first encounter it, and the next set of features will be worked on to be incorporated into version 2.0.

In keeping with our Computer Science department’s approach of naming certain spaces after field luminaries, the lab has now been named the Robin Milner Lab, after a former City academic who developed programming languages and frameworks that came to be used in the field of AI.

In this talk today, I have presented three case studies of projects from City, University of London that I have been involved in, which describe the use of technology-enhanced learning approaches in different postgraduate educational contexts.

With the story of the Robin Milner Lab, we have considered a way that pedagogy might inform designing for technology-enhanced learning.

On introducing Poll Everywhere to the BPTC, we have considered a pedagogy-informed approach to scaling up TEL.

And with our group infographics assignment for academic development, we have looked at a means of incorporating digital capability development into postgraduate education.

It’s now over to you — what questions has this talk raised for you?

References

Davies, M. W. (2009) ‘Groupwork as a Form of Assessment: Common Problems and Recommended Solutions’, Higher Education, vol. 58, no. 4, pp. 563–584, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40269202.

Habel, C; Stubbs, M. (2014); ‘Mobile Phone Voting for Participation and Engagement in a Large Compulsory Law Course’, Research in Learning Technology, 2014; 22(0), [online] Available: https://digital.library.adelaide.edu.au/dspace/bitstream/2440/84973/2/hdl_84973.pdf

Lachkovic, R; Nag, S; Pates, D; (2019) “Get those phones out: using in class polling on a large scale postgraduate law course”; Conference poster; Learning At City Conference 2019; City, University of London; [online] Available: https://www.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/475353/Poster-9-Get-Those-Phones-Out-Learning-At-City-Conference-poster.pdf

Nag, S; Lachkovic, V; Pates, D; (2019); “Connecting students through In Class Polling”, Learning and Teaching workshop; University of London Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching Symposium 2019; 19 September 2019; [online] Available: http://bit.ly/UEL-CLS-PE

Radcliffe, D; Wilson, H; Powell, D; Tibbetts, B (2009). Learning Spaces in Higher Education: Positive Outcomes By Design. Proceedings of the Next Generation Learning Spaces 2008 Colloquium. University of Queensland, Brisbane.

Windscheffel, R (2019). Case Study on posters and group work: Diversifying assessment on an MA in Academic Practice. Educational Developments 20.1, March 2019. SEDA.