Some projects come to us in LEaD Digital Education as fully formed ideas. Our role then is to help to execute somebody else’s vision for educational excellence. Other projects emerge out of iterative conversations and the scramble around for ideas that might just work. The ‘Team Up’ project was one for the latter category.

Enter the drones

Back around early 2019, I’d found myself in an unusual situation. Languishing under a wind tunnel in one of the Engineering labs at City were a couple of boxes of drones, gathering dust. The drones had been part of a previous research project and along with a handful of other colleagues, I was trying to figure out what to do with these small unmanned aerial vehicles. It took a few more conversations until the answer clicked into place, but once it did, it led to one of the more intriguing pieces of work I’ve been involved in at City.

I’d long been looking for good opportunities to foster interdisciplinarity at City, and these drones turned out to be just the right vehicle to do so. The project ultimately brought together two academics from Business and one from Engineering to run a pair of classes at the City Sport gym, where students got to learn about and fly drones, and to consider potential uses for them for business and society.

LEaD had historically worked with both of the Bayes (formerly Cass) academics on similar projects in their technology-led teaching, but with the use of VR headsets instead. The technology was no longer quite so novel for these academics after a few iterations of the VR classes, so both were casting around for some new tech to run these classes with. Step forward, those dusty boxes of drones.

Teaming up to fly

In the case study video below, Drs Martin Rich (Bayes) and Chetan Jagadeesh (SST) recount their experiences on the project, from the undergraduate angle. Martin’s cohort were final year students from BSc Business Management and a collaboration with Chetan, kindly hosted at the CitySport gym, gave him an opportunity for his students to think about how drones could be used for practical business applications. Martin spoke about being part of a collaboration that drew in different people from across the university and which enabled something that no individual part of the university would have been able to achieve alone. Working with the gym meant that we were not flying the drones outdoors and so were not bound by the same rules and regulations that would have made something like this much harder to get off the ground.

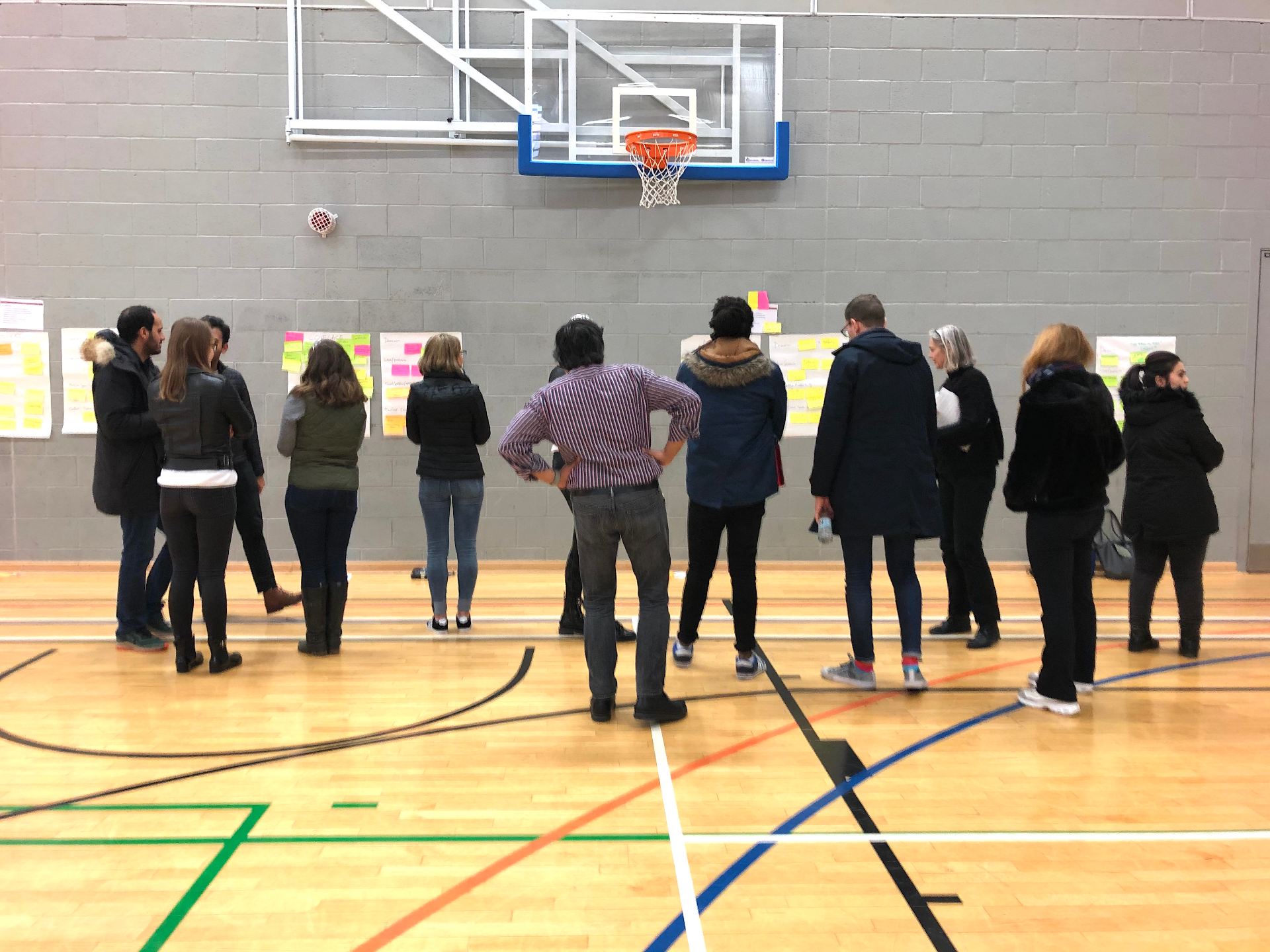

In the class, Chetan helped the students to understand more about the physics of how these technologies fly and gave them some basic piloting skills training. In groups, the students got to try out flying the drones for themselves and then sat together trying to think up new business ideas using drones. There was a great buzz in the gym about this particular initiative, which was quite different for the students from just reading about these objects. Martin reflected that ‘we came close to achieving an element of flow (in this class, which is) an incredibly tough thing to achieve on occasions, and incredibly worthwhile thing to achieve when you do it’. Chetan felt that he gained from the collaboration too, saying ‘we should be collaborating. There’s no point in just sitting in your own office…hammering away at the same things. It’s always good to look outside’.

…

Ideation

We ran a second class with Postgraduate students too, on Dr Sara Jones’ Masters in Innovation, Creativity and Leadership programme (MICL). The best part of these two classes, of course, was listening to the ideas that students had come up with in their group discussions for business and social uses for drones.

With the UG class, some of the discussions centred around drones being able to go to places that humans feasibly can’t (or shouldn’t) go to. This meant being used for doing dangerous work like nuclear inspections, exploring mines for gas leaks, for fire rescue purposes by going into burning buildings to look for survivors, even inspecting train tunnels in the case of accidents or derailments. Other infrastructure-type uses that were suggested included increasingly common ideas like delivery drones for food or other packages and air taxis for larger drones.

There were suggestions about using them for exploration, for humanitarian aid purposes, or even for things like festival photography and other requirements for images of crowd sizes. This led to a discussion about the potential democratisation of aerial video, something which had previously been the domain of large media companies, police units or military teams that would have budget both for helicopters and for helicopter pilots and skilled camera crew. Practical discussions centred around how the plummeting cost of these objects could lead to forms of chaos, about new skills needed and how certain skills would be valued, as well as cases where there would be less need for the kind of infrastructure required to put on forms of public or goods transport such as more train tracks.

For idea generation, Sara’s class was framed more around the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and utilised a framework used on the programme for generating new ideas. Her students also came up with suggestions of drones being used for food and medical deliveries, couriering items to remote places, aerial surveillance, crowd monitoring and crime detection, and for cinematographical or meteorological purposes.

The potential uses for environmental purposes were fascinating, from detecting or stopping forest fires and pollution detection to marine conservation through mapping and collecting rubbish slicks out at sea, and even utilising drone swarms for cleaning space junk. They also considered some really interesting humanitarian uses, such as delivering leftover food to homeless people, rescuing people stuck in dangerous environments, and – my personal favourite – for beaming holograms of teachers into war zones where schools had been destroyed so that children could continue their educations. Whether some of these ideas were technically feasible or not at this stage didn’t matter, as good ideas have to start somewhere.

Project reflections

We’d originally referred to the drones project under the name ‘Co-Pilots’, as that seemed to capture both the collaborative nature of the project as well as its relationship to airborne objects. However, the term subsequently ended up being used to refer to the in-class support that academic staff now get for hybrid teaching, as facilitated by the ISLA project, so we had to go back to the drawing board for a new name. ‘Team Up’ seemed to have similar associations, so that’s the new name I’m using to refer to this particular project.

This was a case study that I’d hoped to be able to tell a couple of years ago. We shot the interview material for the above video around the time that lots of people were nervously keeping one eye on the news about the mystery virus that had recently emerged and was starting to spread rapidly around the world. The world then turned on its head, all campuses got locked down and attentions turned to other things. By the time I’d managed to get my hands back on the footage and start turning it into the story told here, the relationship between higher education and digital technologies had become quite a different one and we’d all been through several iterations of locking down and unlocking. Given the renewed post-lockdown focus on student experience and encouragement for a return to campus-based activities, as well as the role of interdisciplinarity in teaching about the wicked complex problems we face in the world these days, I felt this case study was a story still worth telling.

Crossing boundaries

Multi- or interdisciplinarity is not uncommon in research contexts. City has research centres such as the Interdisciplinary Centre for Creativity in Professional Practice (the centre behind the MICL), the Centre for Culture and the Creative Industries and the London Space Innovation Centre that draw on academic expertise from across the university.

From climate change, war or migration to new technologies in the digital revolution or the ongoing nature of social inequalities, the world our students will graduate into gets ever more complex, challenging and intersectional. Arguably, more collaboration between academic staff in programmes would bring wider perspectives to disciplines and the challenges our students will face in their personal and professional lives.

Many higher education institutions have already started embracing interdisciplinarity in their programme offers. City, of course, already offers the MICL, which has been accepting students since 2010 and brings together perspectives from business, the arts, psychology, law, design and digital technologies. UCL offers a three-year BASc interdisciplinary programme linking the arts, social sciences and more traditional sciences. Manchester University has a University College for Interdisciplinary Learning, with units, programmes and challenges that students can take as part of their undergraduate degree. The London Interdisciplinary School was founded in 2017 as a new UK university dedicated to studying complex problems through interdisciplinary learning. James Madison University in the US operates an initiative called JMU X-Labs, describing it as ‘an ecosystem specifically designed to teach innovation with intention and nurture a culture of creativity’ with trans disciplinary programming that challenges students to ‘confidently tackle problems that resist easy solutions’.

What might the vision for an ‘InterCity’ approach look like? That would, I think, be a topic for a different blog post. Hopefully though, this case study gives a hint of some of the benefits that both staff and students can gain from teaming up with others from outside their own disciplines and silos. As Chetan says in the video above, if you have an idea for an educational collaboration, why not reach out to LEaD to see if we can lead you in the right direction?

If you have collaborated with others in your teaching at City, please share your experiences in the comments below.