Are you looking to take teaching online further, having moved teaching activities online during the pandemic and experienced some of the possibilities that online learning holds? What if you could purposefully bring students from different parts of the world together for an immersive and highly engaging series of extra-curricular activities but without them having to all travel to be in the same place? Virtual Exchange, the practice of technology-enabled education programmes between individuals or groups that are geographically separated, provides some options to these questions.

The significant expansion in the kinds of tools and practices available for online education presented by the pandemic has left City, University of London (City) with more means for enabling and supporting these sorts of initiatives than were available pre-pandemic. In June 2021 the Digital Education team, part of Learning Enhancement and Development (LEaD) here at City, received a request from Sandhya Drew, Assistant Dean (International Students and Exchanges) at the City Law School to help plan and support the school’s first Virtual Summer School, on the topic of Human Rights and Business. This blog post describes how we collaboratively planned, delivered, and evaluated this valuable international learning experience.

Contents

Background

The Virtual Summer School was organised between City Law School and a partner university, O.P. Jindal Global University in India, and was free for students. The event itself ran for two weeks, from 10.30 am BST for around 3 hours each day. Each day, guest speakers from European and Asian universities as well as representatives from leading law firms spoke on a range of topics from human rights and vaccines to digital censorship, labour law and business. Students worked together in teams to deliver a final group presentation to the whole class on the final day. In total, we had 54 students participating, working in 10 separate groups. A key aim of the Virtual Summer School was to provide an opportunity for students to work collaboratively online with students from another jurisdiction.

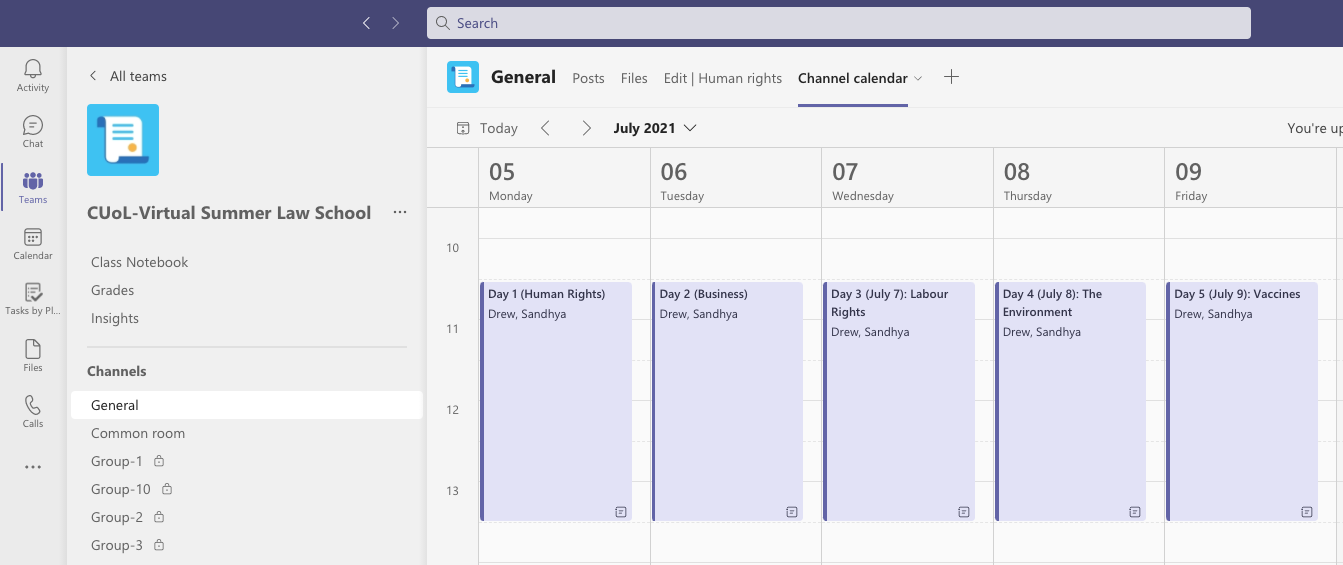

From a Digital Education perspective, this initiative also gave us an opportunity to explore the Virtual Exchange format, by bringing two globally minded universities together and finding new ways to provide an excellent student experience. We had several online planning meetings with Sandhya Drew (City Law School) and Malvika Seth (OP Jindal Global University) in which we discussed the requirements and how these could be achieved in an online environment. Our intention was to provide a highly interactive social experience as opposed to more formal one-way delivery with traditional lectures. We discussed at length the benefits of using Microsoft Teams rather than a traditional learning environment like Moodle to host learning content and to run daily lectures and activities. There were several reasons for this: students and external speakers with guest access would be able to access Teams easily in their own time zones, we could create private channels for group work, and facilitate collaboration with access to PowerPoint in one place. A bespoke learning environment that is centered around effective collaboration can be quite easily built using the basic elements of a Teams site.

We agreed that the Virtual Summer School should have the following components in terms of its design:

- Live guest lectures/presentations. The requirement was to run these as smoothly as possible. Students could turn on their cameras and microphones to ask questions.

- Interactive activities, including a virtual Escape Room

- Private channels for group collaboration

- A Common Room channel to provide a space for social activities and introductions

- A Technical Support channel to help students and speakers with any issues

- An evaluation session and survey to gather feedback on this unique experience from a student’s perspective

A significant amount of training, guidance materials and testing were needed for implementing all these components. We spent plenty of time testing Microsoft Teams and working out which of its functions best served our needs.

Let us hear from Sandhya and Malvika who talk in the video below about their experience of working on this project together with LEaD:

Learning experience

A survey was distributed to students on the final day to obtain their feedback on the learning experience, technology, and teamwork. The survey received a total of 35 responses. There was very positive feedback from a great majority of respondents with regards to their overall experience which is presented below:

How was your overall experience of the Virtual Summer School?

Some highlights from students’ responses included:

- The most enjoyable experience was a one-to-one question answer session with the guest speakers. It not only helped me clear my doubts but also soak in the unique ideas that other people proposed.

- Interacting with my peers from across the world while preparing for the final presentation would be the highlight for me. We had a lot of fun. The lectures by eminent professors also helped me to enhance my knowledge.

- The one thing that I enjoyed the most was interaction with people from different parts of the world. The entire summer school was a very valuable experience for me in terms of the plethora of guest speakers that we had talking about different aspects of human rights and business law.

Overall, all students described their experience of working in a group positively, with over half of those surveyed describing it as ‘excellent’. We received many further positive comments from students about the group work, including:

- I really loved the diversity of opinion and expertise that everyone brought. We heard each other out.

- [What worked best in the group work?] It was the coming together. My group was excellent, and we shared wonderful stories together.

One of the activities we built was the virtual Escape Room, using Microsoft OneNote. This consisted of a series of pages, each containing a relevant quiz question and where progress was made via password-protected links to subsequent pages. The answer to the quiz questions provided clues for unlocking the passwords. This activity was mostly very popular with the students, who recalled the Escape Room activity as ‘fun’, ‘interesting’, ‘a creative icebreaker’ and ‘a great introduction to get to know your team’. One student even described it as ‘one of my best and favourite memories’ from the Summer School. Find out more about how to put your own Escape Room together in OneNote using this YouTube tutorial.

In terms of what could be improved in later editions, we asked for a single suggestion for how the Summer School could be improved in future. Students overwhelmingly asked for more interaction with each other and more group activities, to get to know each other better and to break up the longer presentations. Further suggestions included more quizzes, polls, game nights, additional activities like the Escape Room, more breakout sessions, greater opportunity to interact during the guest speaker talks, and for mixing up the groups to provide them with greater opportunities to meet other students on the summer school. Other feedback included having more breaks during the live sessions.

It is easier to be able to rely on serendipity, changes of plan or impromptu activities when all students are meeting in person. One of the factors for events that are run wholly online is that they require more planning and preparation in order to work well. Although we would have liked to have included more opportunities for interactivity and group work in this project, planning and preparation time was fairly limited. The Escape Room activity therefore gave us a chance to test the water with something social that was also connected to the topic. If we do this again, more group work and opportunities for interactivity is clearly an area that needs a bit more thought and the student ideas were very helpful in this regard.

Communication

One of the reasons for providing the private channels for groups was so that students not only had a space to collaborate either synchronously or asynchronously away from the main group interactions, but also so that it provided them with a general mechanism for communications. Interestingly, 14 students also described using WhatsApp for communication, either alongside or instead of Teams chat. Students described their motivations for using WhatsApp:

- (We) … also used WhatsApp because its easiest to actually contact everyone/receive notifications and we are on WhatsApp more often!

- (To) ensure a better and quicker communicating to all of our devices

- Because of technical issues and also WhatsApp is a sort off informal app so we can also be available out of working hours

- WhatsApp is more convenient all round, people tend to have problems with Teams far more frequently

- We used WhatsApp as well to have frank conversations which would not be monitored by authorities

- (We) also used WhatsApp to have all the students, not just your group in one chat

Naturally, WhatsApp is not a university-provided or supported platform, so we were not able to design or plan for how students could use it to support their involvement. It was interesting to note, however, that students self-organised in this way using the easiest tools they collectively had on hand. Not only did WhatsApp deliver a more consistent experience for the basic requirement of communications with each other, but it also provided a space that they felt was more private to them. While we purposefully tried to develop a platform to fully provide for participating students’ needs and requirements, an instructive lesson perhaps here is that in convening a geographically dispersed group of people around a particular task, they nevertheless found ways to work together outside of the provided structures, despite our efforts to cover these essential bases. Put another way, if different communities of students are brought together online and they see value in collaboration with each other, they will find a way to ensure that they can.

One other point of note that emerged from the evaluation comments concerned the question of whether cameras should be on all the time or not. One student remarked that ‘all the students’ mikes and cameras need not be regulated to this extent’ while another stated that ‘the pressure to turn cameras on was unneeded especially if you were not talking in my opinion’. Students had been requested to keep their cameras on throughout, where technically feasible, to ensure engagement in the event. Faces being visible in an online classroom environment via webcams can often be seen as a proxy for engagement and participation, in the same way that attendance or ‘just turning up’ can be viewed as a proxy for engagement and participation in the physical classroom. Students, however, can have a variety of different reasons beyond technical deficiencies for preferring to keep cameras mostly off during online sessions. See LEaD’s ‘Student cameras on/off’ guide for a closer look at the issues behind this and ideas for engaging students without the use of webcams in online classrooms.

Conclusion

From a LEaD perspective, the City Law/O.P. Jindal Virtual Summer School served as a great opportunity to pilot a Virtual Exchange (or COIL, aka Collaborative Online International Learning) initiative, which one of us had been looking for a vehicle to explore this with since before the pandemic. A Microsoft Teams site, made widely-available across the institution during the first lockdown, worked well as a platform for facilitating an inter-institutional educational collaboration, but effective planning and preparation was key to the project’s success. Students from both institutions overwhelmingly had a positive experience and got a lot out of the experience, but clearly needed more provided in the way of group activities. For us as organisers, while it would be important to plan for places for communication and organisation within the platforms we build, we should also expect some degree of self-organisation.

We hope that this case study has provided some insight into the possibilities offered for cross-institutional online collaboration and will be useful for colleagues looking at issues such as internationalising the curriculum, building intercultural competencies for students, developing a more strategic blended learning approach, or looking to leverage City’s educational platforms more effectively for enhancing the educational experience. If you would like to discuss your own ideas for a Virtual Exchange initiative, please contact your LEaD school representative.