Contents

The journey so far towards wireless collaboration at City

This is the second in a series of six posts about LEaD’s investigations into introducing wireless collaboration technologies to City learning spaces. It covers the rise of smartphones and mobile devices, increasing demand at City for integration of mobile devices within learning spaces, and how LEaD responded to that demand by launching investigations into wireless collaboration.

Little connected computers

The first iPhone was introduced to the public in June 2007. It had a multi-touch touchscreen for interaction, mobile, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity and a range of different sensors, as well as a camera and a host of native apps. It was not the first smartphone, a device that converged the palmtop PDA computing that was popular at the turn of the millennium with the affordances of wireless telephony, and which was coined as a term in 1995. The iPhone is widely considered, however, to have popularised the thin, slate-like form with the emphasis on a touch interface, and thus led to the exponential growth in the smartphone as a widely adopted consumer device. The following year, Apple allowed developers to start creating their own apps, which could subsequently be downloaded to the device from the App Store that the company had opened as a platform to provide aggregated access to their hardware. The number of apps that have been subsequently downloaded via the App Store is consistently touted when the company launch new products, and typically has a lot more zeroes than ones in the figure given.

Palm or pocket-sized devices with computing capability had been around long before Apple hit on the iPhone. In the early 21st Century, the BlackBerry was the dominant gadget that allowed owners much of the functionality of email, but fully portable. Apple themselves transformed the personal music player with the release of the iPod, essentially little more than a small-in-size, high-in-capacity hard drive that a touchscreen was later added to. A very far cry from the Sony Walkman of the early 1980s, given that you could carry your entire music collection around in your pocket rather than just two sides of a cassette on your belt. I remember trekking excitedly to Tokyo’s Akihabara electronics district in something like 2004 to buy myself a Palm Pilot when I lived in Japan. I wrote a third of a book on the tiny thing during my lunch breaks. It had SD card storage capacity too, so I could transfer files from it but, even in Tokyo, it was a struggle then to find a receiver that I could fit it with which would endow it with Internet access.

The Apple tree grew. The first iPad was released in 2010, taking the iPhone screen and making it much bigger. Equally exalted and slammed at the time – a wide range of capabilities made it a potential competitor to netbooks and laptops, but you couldn’t connect most common peripherals or run anything Flash-based on it – it nevertheless sold in the millions and led to the large and rapid growth of the tablet market. Somewhere in between these two items, the first device running Android was launched, which was an operating system designed for mobile developed by Google and based on a version of the Linux kernel. Android would ultimately come to be a more widely-spread mobile operating system than iOS, its main competitor. As Microsoft and Apple came to dominate computing in the PC era, so did Google and Apple during the mobile one.

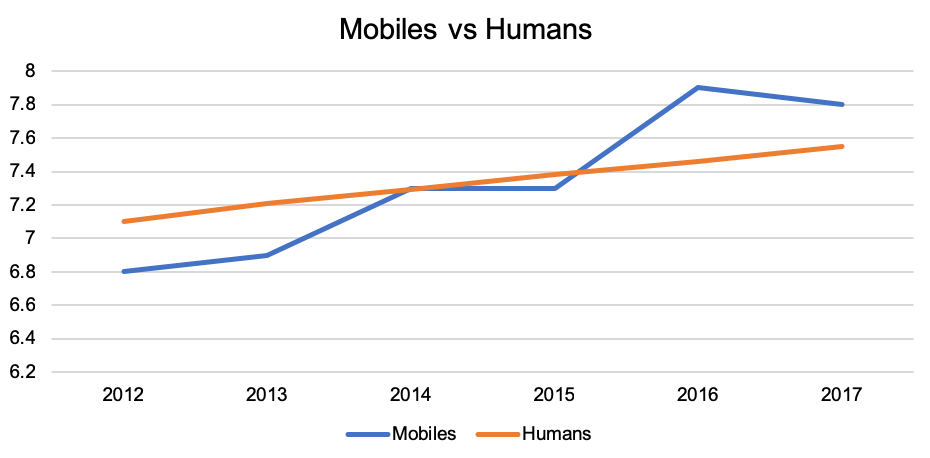

The graph above takes two elements – the number of mobile phones in world and the global human population – and tracks them both over the past six years. The figures for the growth of the global human population is taken from Worldometers.info, while the figures from the growth in number of active mobile devices (based on current SIM connections) comes from GSMA Intelligence. Based on these figures, mobiles overtook us in 2014. They seem to be growing faster than us too. According to GSMA, over 57% of those mobile connections are now smartphones.

Identifying wireless demand at City

It was, of course, only a matter of time before the proliferation in the availability and usage of powerful, pocket or portable computing devices impacted on teaching and learning, even in the notoriously slow-to-change world of higher education. As with most higher education institutions, City has seen increasing demand from academic staff for our learning spaces to facilitate more effective use of mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets in teaching and learning.

One of LEaD’s predecessor organisations, the Learning Development Centre (LDC), surveyed 816 City students across all schools in 2010 about their mobile device usage. They found that ownership of smartphones and laptops was high, and that City’s technical systems needed developing further to better support mobile usage. They also found student appetite for using their devices for receiving and viewing teaching-related activities or for the delivery of educational content, but less so for interacting in class. Given that the broader socio-technical environment is now considerably different from 2010, that many staff report notable student engagement in class via using the likes of Poll Everywhere, and that as with most universities these days, ubiquitous connectivity is a given feature of the campus experience, it could be very worthwhile to run a follow-up to this survey to help inform the extent of the potential demand for wireless collaboration as a key feature in all learning spaces.

The LDC ran an evaluation of teaching pods the following year, that produced some feedback indicative of a direction of travel. One member of staff suggested ‘offering the opportunity for people to give lectures away from behind the Pod’ while another suggested that ‘it would be very convenient to have a means of sharing information through projection…in smaller rooms’ and that ‘something you can hook up a portable to’ might be sufficient, rather than needing a full lectern.

In early 2014, 62 members of academic staff completed an educational technology survey. Five respondents mentioned an interest in being able to connect wirelessly to the teaching pod with a mobile device. Another mentioned wanting to be able to move away from the pod, indicating the importance of mobility in teaching. Eleven staff specified that they’d like to see wireless projectIon for staff devices in learning spaces in the future. This survey was later followed by a set of staff interviews, asking academics specifically for their feedback on learning spaces and how they used them. Sharing content wirelessly via the projector came up again as a theme, along with the need for improved connectivity. Interestingly, enabling students to utilise their own devices more effectively in their learning emerged from these interviews, as the below quote indicates:

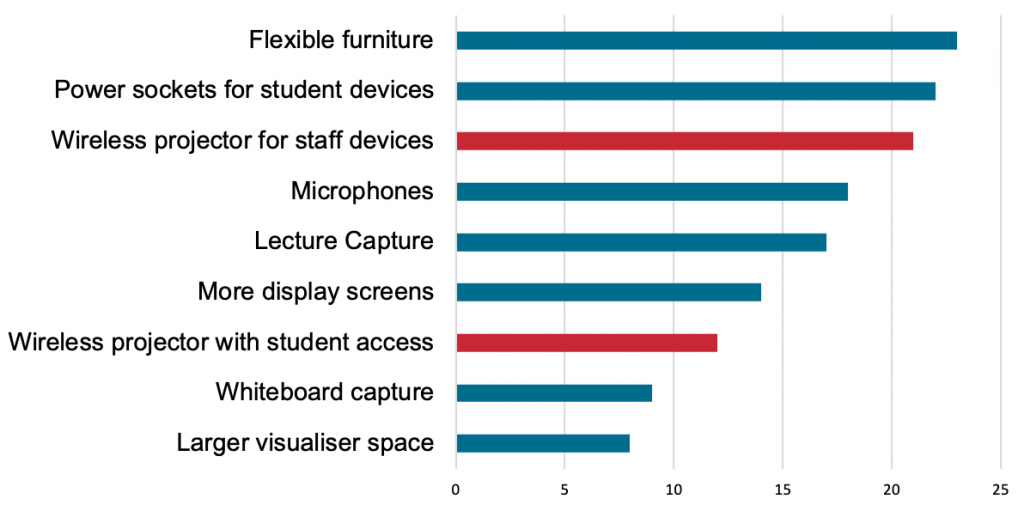

In a subsequent staff survey the following academic year, one respondent asked for a way to project content to other devices or some means of sharing in group work. Wireless projection of both staff and student devices was an increasingly popular option for future space developments, as the graph below of responses to the question ‘What would you like to see more of in City’s lecture and seminar rooms to better suit your teaching requirements?‘ indicates:

Finally, staff and students were interviewed following the opening of the Drysdale Lower Ground suite of rooms. One staff interviewee mentioned that they had been trying out a means of capturing their whiteboard writing electronically, and would like to be able to write on a tablet computer in future and project their writing that way. Another respondent suggested being able to control sound and image from their laptop would give them more flexibility, whereas the ability for students to annotate on their devices and be able to project onto the screen was also considered useful.

Searching for that magic box

When I joined LEaD in 2014, the department had been gathering all this evidence with a longer term view on upgrading the teaching pods across the teaching estate. This was intended both as part of an overall refresh of in-class educational technology provision that looked to the future as much as a means of renewing outdated equipment and fixing what needed fixing. Within that project, then dubbed ‘Pod 2.0’, I was responsible for investigating the wireless presentation aspects. From that emerged two clear aims:

- To enable staff to present and control content from their own mobile devices wirelessly to the projection screen

- To enable students to present content from their own mobile devices wirelessly to the projection screen.

Sounds simple enough, right? Pod 2.0 later evolved into the more substantial ‘Designing Active Learning Initiative’ (commonly known as DALI), which was focused on renewing all learning-spaces-related educational technologies across City, a multi-year project that looked at in-class technologies and staff interactions with them. Under DALI, a third aim was added for wireless provision:

- To allow staff and students to annotate content displayed on the main projector screen on their own mobile devices.

Being able to share high-resolution images, video or apps wirelessly – as easily achieved in the home through domestic technologies such as Apple TV or Chromecast – has been a challenge that many institutions across the higher education sector, including City, have faced. Before going into greater detail of what has been done at City in terms of attempting to bridge that gap so that such technologies can be used for educational purposes, a word first on terminology.

We have specifically chosen to use the term ‘wireless collaboration’ over ‘wireless presentation’ to describe the kind of technology that we’re looking for. The DALI project has essentially codified part of LEaD’s approach to the promotion of digital technologies as being largely around means of enhancing forms of active and collaborative learning. To focus our framing of this emerging technology on the presenting aspects of it would be to concentrate on it as a teacher-centered tool. While this is an important aspect of it, it is necessary to also recognise what it can enable from a learner perspective too.

Seeing it also from a learner’s perspective underlines that such a tool further encourages HE to continue in the direction of travel towards greater learner-centredness, although it also sows potential seeds for wireless collaboration as a contentious technology to those resistant to this particular direction of travel. Nevertheless, we have settled on ‘wireless collaboration’ as our key term, which we define as two or more people working together to complete a task or achieve a goal, which is enabled by the use of mobile digital devices and where content can also be shared to a common display. Naturally, this definition is intended to encompass wireless presenting too. Interestingly, it seems that since we first started looking in this area, many device manufacturers have started moving towards using the same term.

Evaluating candidate technologies

Our initial research consisted of investigating existing technologies that might be able to meet our identified aims, primarily of enabling staff or students to share any content from their mobile devices wirelessly to a main display. Both hardware and software solutions were identified, along with three key protocols that enabled wireless sharing (‘mirroring’) – AirPlay for iOS and other Apple devices, Miracast (a direct peer-to-peer connection commonly used for some Android and Windows OSs) and WiDi (an Intel-developed wireless transmission protocol that was built into many projectors, but which has since been discontinued in favour of Miracast). Sector suggestions for possible technologies came via universities at Warwick, Southampton, Manchester, Keene, and Oxford, mainly via the Association of Learning Technologies (ALT) mailing list. Between July 2014 and July 2015, several demonstrations from product vendors to LEaD and IT staff were run, both on and off site.

Ten products were considered as part of a longlist, both hardware solutions and software ones. In discussion with IT’s Specialist Services, this longlist was then reduced to four possible candidate technologies, which were subsequently presented to staff in two workshops with the aim of choosing one technology for a pilot project. During November 2015, technical staff from LEaD and IT attended a workshop to demonstrate those four candidates. A second workshop was run for academic staff, by which time the options had been reduced to two. The Solstice Pod by Mersive was selected from these to be installed in the Civil Engineering lab (see case study post here).

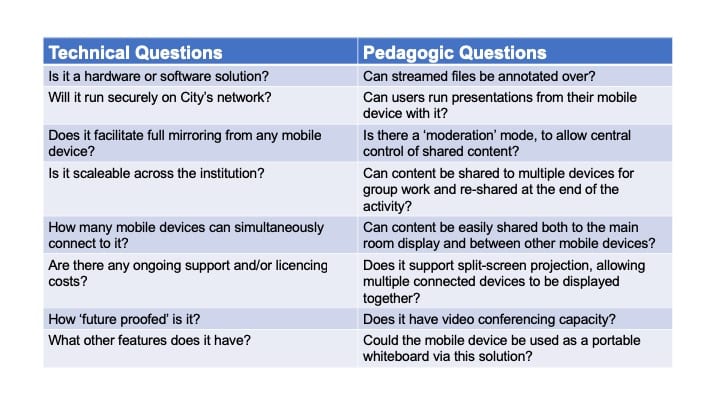

Around about the same time, SCHOMS (Standing Conference for Heads of Media Services) conducted a similar activity on behalf of the University of Exeter, and produced a report that came to different conclusions than City’s range of technology assessors. It should be noted here that wireless collaboration is still very much an emerging technology, particularly for higher education markets, so these particular products will no doubt have developed in a range of ways since our initial review. Nevertheless, the Solstice Pod was simple enough to use, robust enough and met more of our requirements than the other products assessed at the time. The criteria used were both technical and pedagogic, and are listed in full in the table below:

Challenges and activities

There were several significant barriers to finding and implementing the right wireless collaboration technologies. Starting with the principle that any solution had to be fully platform-agnostic (supporting at least iOS, Android, macOS and Windows platforms, running on smartphones, tablets or laptops, given that these were the range of devices used by our staff and students), and allow full-screen mirroring (rather than limited document sharing or access to a device’s camera roll), it was discovered that many initial solutions didn’t support these two key functionalities. The overall assessment in the earlier stages was that the market itself wasn’t fully ready for a product that met the requirements of the higher education sector. Our dialogue with some of the vendors led in some cases to functionalities being added to the products, such as iOS mirroring being added to DisplayNote software. Most solutions did not have the annotation functionality that we were looking for either.

The ultimate goal was to find a single solution that met all our requirements and which could be integrated into a new model of teaching pod, to then be deployed at scale across the institution during the lifetime of the project implementation. However, finding a single solution when the market wasn’t ready and when most products met different parts of our requirements list but not all of them was a significant challenge, particularly in combination with the issue of running these products securely on City’s network. One of the products had annotation capabilities built in to its functionality, but it proved not to be suitable in other ways. The annotation aim was subsequently deprioritised as one of the primary drivers within the investigation.

Two other key activities followed this shortlisting were a research staff seminar and working more closely with IT. The seminar was conducted in November 2016, with researchers from City’s Human-Computer Interaction Design (HCID) department. Aimed at introducing wireless collaboration to more staff and uncovering other possible uses of the technology, usage suggestions included sharing student-generated resources, live presentations of hardware or other equipment, demonstrating website walkthroughs, sharing complex content like coding, and for running Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) computer labs. Discussions with IT centred around establishing how any chosen solution could run on City’s network in a secure and supported way, an issue that according to research had been problematic to overcome for other institutions. After several conversations with City’s network manager, an approach was devised whereby wireless collaboration devices could be deployed securely and run on eduroam, which felt like a significant breakthrough.

In investigating trying to facilitate greater use of mobile devices in higher education, I stumbled across a paradox. The next post explores that paradox and looks beyond finding the magic box to what the use of mobile devices might bring to university teaching and learning.

Questions for comments

- What do you remember about your first Internet-enabled pocket device?

- How would you define ‘wireless collaboration’? Would you choose a different term/phrase to describe this technology?

- How have you introduced wireless collaboration into your institution/teaching or learning space?