Contents

On mobile learning and higher education

This is the third in a series of six posts about LEaD’s investigations into introducing wireless collaboration technologies to City learning spaces. It covers a paradox identified in trying to facilitate greater use of mobile devices in learning spaces, the emergence of an overarching research question, and some wider thoughts on the use of mobile learning in higher education.

Digital capabilities

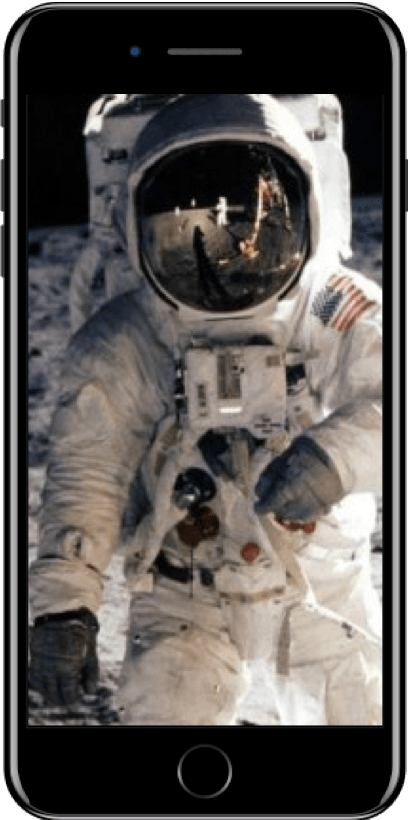

Part of the Apollo space mission in 1969, the Lunar Module that enabled astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to land on the moon’s surface had a digital computer installed on board. Called the Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC), it didn’t load and run the pre-written instructions we now commonly understand as software or store them in a writeable medium. The AGC’s instructions were literally woven together into ‘core rope memory’ by physically stitching 0s and 1s together with magnetic strands, by hand. Still, a digital computer augmented all of NASA’s marshalled resources and helped humans set foot on the moon for the first time in our history.

Comparing the AGC and the iPhone is obviously a fairly spurious exercise, given that they are such completely different machines. Nevertheless, there are some metrics we can look at when placing them side by side, given that they are both essentially digital computers that receive data inputs, process that data, then output it in some way. The AGC weighed 31.75kg, whereas the iPhone Xs – Apple’s most recent high-spec iteration of its flagship computer – weighs just 177g. AGC had a processor speed of 1 MHz, the iPhone Xs clocks up 2.49 GHz. AGC’s RAM size was given at around 4KB, whereas the Xs’s is 4GB. We might not all have the rocket power of the Apollo missions, but the computer that most of us carry around in our pockets is arguably more powerful than the AGC, and in some cases, by several magnitudes.

I did the majority of the reading for the first year of my MA on an iPhone 4. It required – admittedly – a lot of pinch and zooming on a really small screen in my lunch breaks, but with a bit of discipline, it meant I could cover the materials and fit my studies around my work. During the darkest days of my commuting experience in 2016, when the rail network was beset by constant delays, faults, industrial action and apparent corporate malfeasance, I decided to make a documentary about my struggles to travel between work and home. The resulting film ‘Journeys By #SouthernFail’ was almost entirely produced using an iPhone 6s. It was no moon landing, for sure, but this nevertheless served as a very interesting exercise in pushing the capabilities of the networked pocket computer I always keep with me.

In considering the possibilities of what could be created using just a smartphone, I’ve often also been mindful of the fact that The Beatles ‘Sgt Pepper’ album – a cultural high watermark in its time – was recorded and produced on a four track recording studio, and it required the gravitas of being a successful recording artist in order to just be able to access EMI’s Abbey Road facilities. Today’s young musicians can access 32 track recording capabilities using just GarageBand for iOS. What would The Beatles have done with iPhones?

Ban them!

Walk along the corridors of a university and you can often see academic staff striding off to class, perhaps with a laptop or tablet device augmenting the clutch of papers under their arm. Visit any lecture theatre in any higher education institution (HEI), and if you listen closely enough, you can hear the understated rhythmical clatter of the tapping of keys all around the room. In university libraries, students might be surrounded by shelf upon shelf of books, but look around and you’ll more likely see them immersed in a screen rather than a paper page.

In November 2017, Prof Susan Dynarski from the University of Michigan became one of the latest in a long line of people to propose the banning of electronic devices in lectures. ‘I generally ban electronics, including laptops, in my classes and research seminars’, said Prof Dynarski, adding ‘That may seem extreme…But a growing body of evidence shows that over all, college students learn less when they use computers or tablets during lectures. They also tend to earn worse grades.’ She was reacting to seeing a ‘sea of students typing away at open, glowing laptops as the professor speaks’ and finding the situation wanting.

In a riposte to Dynarski’s diatribe against devices, Seth Godin questioned the very nature of a lengthy monologue to a large crowd and suggested that ‘the solution isn’t to ban the laptop from the lecture. It’s time to ban the lecture from the classroom.’ Dynarski and Godin give us two possible poles of the debate on the use of mobile devices in higher education – that they are either too disruptive to enhance learning, or that the augmentation of learning with mobile devices illustrates the redundancy of certain methods of teaching.

A happy medium probably sits somewhere in the middle. If Godin has a point, however, and that different ways of teaching than lectures are more effective ways to learn, what might his ‘interactive conversation(s)’ or ‘participatory seminar(s)’ look like if they are augmented by the powerful, portable computers that almost all students have with them at university these days? Many City staff already incorporate mobile devices into their teaching, through working with apps like Explain Everything for recording simple screencasts or via the use of Poll Everywhere as a student response system. However, the ability to show content from a mobile device to a class class on a common room display has mostly been restricted to either using a concoction of cables and adaptors, or via placing a mobile screen under a teaching pod visualiser – in both cases thus removing one of the key mobility affordances of such devices.

A paradox emerges

Exploring this emerging technology of wireless collaboration at City has led me to consider a particular paradox. Contemporary socio-constructivist learning theories encourage us to regard learning as much of a social experience as a personal experience. The use of mobile devices in teaching and learning, however, is invariably a personal experience – typified by Dynarski’s sea of silent typists. We could crudely summarise how this articulates as a paradox with the following statement: mobile is usually personal, whereas learning is often or mostly social. The pursuit of the magic box of wireless collaboration is, therefore, effectively an attempt to resolve this paradox. In enabling staff and students to openly share content from their personal devices to a common room display or a larger screen meant for small groups, this facilitates a more social form of mobile learning.

If wireless collaboration technologies can therefore resolve this paradox and allow teachers and learners to move beyond Dynarski’s Canutian angry professor amidst a sea of silent typists, what does that mean for teaching and learning in higher education? In this journey, I’d come to realise a number of factors along the way.

The first of these was that shift described in the previous post as moving from framing this new technology as one of enabling ‘wireless presentation’ to one of enabling ‘wireless collaboration’. It wasn’t enough to make it easy for lecturers to load their slides onto an iPad and move around a lecture theatre a bit more than they might usually be able to do. It had to also make it easier for students to be able to share what they’d been working on, and for their peers to be able to feed back on it from within a collective.

The second factor was that, fundamentally, it wasn’t actually about the technology at all. The benefit of being able to do things wirelessly cuts out the time wasted in class messing about with cables and adaptors, saving people from having to stand up, move around and disrupt the flow of something just to show what they’ve been working on. Ideally, the technology itself should appear almost invisible and allow people to focus just on the content itself. But it was also about what it enabled people to do that they previously really couldn’t do at all, and specifically with mobile devices as a part of the educational mix.

Towards a research question

I’ve been edging towards a research question with this journey. I’ve not clearly articulated it to myself yet, but it runs along the lines of something like this: if the mobile learning paradox is resolved, what can mobile learning bring to higher education? ‘Mobile learning’ could be appended with several other terms here, such as ‘enabled’, ‘socialised’ or even ‘supported’, but I use the common term mobile learning here as shorthand for all those things.

It’s tempting to look at this in terms of the buzzphrases that echo around HE these days, of socialised mobile learning as being potentially ‘transformative’ or ‘disruptive’, and to therefore frame it within the change paradigm. But to do so would, I think, miss the opportunity to bring more staff along with the possibilities here. To give a different educational technology example, lecture capture can be a great aid to students for revision and reflective purposes, but for a variety of reasons, it remains contentious to a proportion of staff in any given HEI.

In order to be able to take fuller advantage of the possibilities of wireless collaboration, I think it needs to be seen more as an enabler than a transformer or disruptor. It is therefore incumbent on those of us in educational development roles to help academics to see what – I’ll return to the opening descriptions – these powerful, networked pocket computers allow them to do in their teaching that they couldn’t otherwise do. This means that this has actually become more of a mobile learning quest than the wireless presenting one it started out as.

I took the Civil Engineering case study from the first post in this series to the University of Greenwich’s Academic Practice and Technology conference last year (see slides above). The audience for my presentation came from technical, academic and professional services backgrounds, and it was helpful to hear that many had shared similar challenges to me in trying to facilitate the wireless sharing of content from mobile devices in their own institutions. More helpful, however, was the invitation to reflect on the themes of the presentation in Greenwich’s in-house educational journal, Compass (read the full article here).

Writing this article got me reading and writing more about mobile learning in HE. It made me aware that such new technologies invariably tend to be adopted within existing teaching paradigms rather than new ones, to consider the unique affordances of mobile devices (as against standard desktop PCs), and to pick up on certain key theories around mobile learning. It also brought home to me that if wireless collaboration technologies were to be installed in City’s learning spaces, such an installation would need to be accompanied with a panopoly of other conditions, including staff development activities, a sustained community of practice, the modelling of effective practice, and even support for redesigning curricula, to have a sustainable impact on the educational experience for teachers and learners.

Over the horizon

Let’s situate this all within a slightly wider context too. Established in 2002, the NMC Horizon Report is an annual report intended to identify and describe emerging technologies likely to impact on education over the subsequent five years. It has a global perspective and covers the main educational challenges universities generally face and specifically with regard to technology in learning. How, then, has the rest of the sector been experiencing and responding to these issues around mobile devices, wireless collaboration and learning spaces?

The 2012 report spoke of people expecting to ‘be able to work, learn, and study wherever and whenever they want to’, of challenge-based and active learning approaches being increasingly emphasised in the classroom, and of the new opportunities presented by tablet computing, which were viewed as devices less disruptive than smartphones. In the following year, the report expected tablets to become widely adopted, describing them as ‘a portable personalised learning environment’ that were also ‘ideal devices for fieldwork’. The 2015 report noted the growing trend towards BYOD and suggested that one of the inherent challenges was ‘facilitating learning environments that are device-agnostic’ and that ‘sufficient infrastructure must be in place to support devices of all kinds’.

By last year’s report, online, mobile and blended learning approaches had moved on to be described as ‘forgone conclusions’. The report noted that mobile devices were now so pervasive that this fact was changing how people were interacting with content and their surroundings. An example from Boise State University was given where a Solstice device was used for the wireless streaming of staff and student content to any of six monitors in an active learning space. Key, the report suggested, was how these models were actively enriching learning outcomes, but it was also pointed out that technical and pedagogical support was still needed for staff to be able to effectively integrate mobiles into their curricula.

Helpfully, the report also highlighted a framework and a set of principles to consider in addressing these points. For supporting collaborative learning, it suggested ‘placing the learner at the centre, emphasising interaction, working in groups, and developing solutions to real challenges’. For incorporating mobile devices, instructors were encouraged to consider the SAMR model (Substitution-Augmentation-Modification-Redefinition) for enhancing or transforming their learning activities. The 2018 report continued a focus on the redesign of learning spaces that would maximise ease of use and flexibility, with learning space technologies moving towards fully wireless provision. I would add one more peek over the horizon to this and mention that 5G as a mobile connection standard is set to start being introduced from 2019, so even faster connectivity can soon be factored into the mix.

The most recent stage of my quest has taken me to Chicago, to present on City’s journey so far towards wireless collaboration at the 17th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning, at the generous behest of a travel grant from UCISA. The next two posts report back from the Windy City and on further explorations into mobile learning.

Questions for comments

- What have you achieved using only a smartphone?

- What do you think mobile learning can bring to HE?

- Do you lean more towards Dynarski’s position on using mobile devices in teaching and learning, or Godin’s? Why?

Excellent body of work Dom. Let’s not forget the new active learning space coming later this year for Journalism with its wireless collaboration system placing students in a sharing situation under the mentoring facilitation of the academic. See the post here…

Thanks James! You get to be the first comment on any of these posts too 🙂

Should be a reference coming to the Journalism Newsroom work on the post due on Monday…

I’ve got a detailed post ready for Monday at 7am, I could post it sooner so you can link to it?

That’s OK, I can take the URL from your scheduled post and add it in there. Thanks for the heads up.

http://blogs.city.ac.uk/learningatcity/2019/01/14/new-active-learning-space-for-journalism/

Thanks Dom. Really enjoying the historical journey you’re taking us on. I too used my iPhone for studying first with the OU and later several MOOCs. Some things were frustrating, for example some platforms didn’t enable you to download videos to the device, but it meant I could do my studying on train journeys, no matter how short, without having to pull out large text books.

With reference to Dynarski, LEaD were asked if we would provide a statement against the use of mobile devices within lectures and being an Ed Tech it wasn’t something I was prepared to write. The advice we gave was about setting expectations of use in collaboration with the students, so that things related to the class – such as looking up key facts, making notes, contributing to polls – were ok, but unrelated activities – such as Facebook and online shopping – were not.

Really interesting and thought-provoking article. I’m just off to present a short session in one of our MAAP modules and I will refer to your article. Its interesting in relation to the recent research about ‘disruptive technologies’ like the iPhone and Ipad. As educators, I also believe we should be taking advantage and not see them as a nuisance. Perhaps ( as Julie says)if we help staff to manage expectations then some might be able to see them less as a disruptive technology.