Contents

Heading back into the room

Early 2022, the tide of the immediate pandemic crisis was beginning to recede. Like many of us, I found myself reacclimatising to not having to focus on such a regular and consistent basis on Covid mitigations. As Winter turned to Spring, I began dipping my toe back into being in the physical presence of colleagues and strangers again, sometimes keeping a mask on, sometimes taking it off and breathing the same air as each other. It feels almost unbelievable to imagine being back in that context now that the country is that much further down the road of assuming that this thing is over and that ‘we have all gone back to normal’ (or at least continue to piece together that next normal), but it still feels useful to recall just how different things were even a little over a year ago.

March 2022, then. With colleagues, I explored how to hybridise a long-running school Community of Practice event, the Bayes Teaching and Learning Exchange, which meant being in the room at Bunhill Row (blog post of tips and reflections here). I followed that up with a day trip to THE’s Digital Universities event as well as a visit to the first iteration of Bett’s then-new HE focused event, Ahead by Bett. With all three events, I managed to spend time on public transport and mingle with large groups of other people again, all without bringing a potentially dangerous pathogen back home. I considered this enough of a success to pitch for running actual sessions at my second in-person only conference since early 2020. Baby steps, back into the room.

I pitched a couple of sessions at that summer’s Academic Practice and Technology conference (APT). This was an event I’d previously presented at when it was held at the University of Greenwich, back in 2017, when mingling with sectoral colleagues was not considered a potential risk to one’s health. George Siemens had been a keynote panellist and was stuck at an airport in Texas instead of being to make the conference. He ended up getting Skyped in to the main stage panel discussion on the fly.

I was in the audience for the 2020 event when the #PivotToOnline was in full swing and communities converged in online spaces, attempting rapid innovation and iteration of things previously largely only done in each other’s physical proximity. Two things I particularly recall from keynotes from that event that I’d never seen before – one speaker gave his address from a field somewhere, leaving me wondering whether his presentation would be interupted by cows, and another keynote speaker briefly paused their talk to announce ‘Excuse me a moment, I just need to check that my washing machine isn’t going to explode’!

The 2021 APT conference was also held online, and this time I managed to make my way back onto the programme and used the session as a launchpad for a new podcast about hybrid teaching in higher education that I was co-producing.

Academic Practice and Technology 2022

2022 would be the first time in five years back in the room at an APT conference. These days, it’s hosted by a much larger aggregation of London universities than the two that were running the event when I first attended, so that makes APT quite the academic development gathering of the great and the good from London HE. I entered the main room rather cautiously at first, mask still on as others were mingling and clearly contending with the same issues. I sat myself down with a coffee and found myself in the midst of familiar faces that were no longer bound by screens. There was something quite liberating about being able to lower a mitigation and say ‘Long time no see, how are you?’ What would once have been an almost mundane greeting became a step into the new world of the next normal. I couldn’t decide whether to keep the mask on, take it off, or toggle between the two, but the whole experience was an overall lowering of the guard. A good thing.

The conference had purposefully been designed as an in-person only event, with asynchronous materials (the ‘presentations’) made available in advance and no online or hybrid components. The intention was to bring people back together to in-person activities and make them ‘purposeful’, so that the conference would be focused more around discussions and collaboration rather than listening to a series of talks. An attempt to try and start making some meaning out of what we’d all been through with the pandemic and what it meant for our practices. I appreciated what the organisers were trying to do and thought it a little bold, but was also mindful of the fact that the onlining of many professional gatherings had led to significant boosts in accessibility to such events. Making people have to attend in person meant a positive move towards bringing people back together again, but also with echoes of the old exclusivity of such gatherings.

The other reason I had for nerves was due to introducing an idea I’d had percolating for about a year and a half into the public domain and being able to gauge the reaction to it. But I’m getting ahead of myself here – I’ll come to that bit later.

The first keynote was delivered by Jonathan Grant, on what he was calling ‘The New Power University’. I’d previously attended an online version of his talk to coincide with the initial book launch, so the content of it wasn’t entirely new. However, it was a useful reminder of the key ideas and was good to position a ‘big picture’ pitch at the launch of the conference, as higher education was emerging from the wreckage of the lockdown periods and figuring out where it stood. Grant made the case that universities have to take lessons from history and step up to the moment they find themselves in to avoid the wider spread of the darker turns that our societies can sometimes take. He also made the point that putting social purpose at the heart of a university strategy can stimulate innovative thinking, and innovative thinking is very much what dark times call for. Read a review of Grant’s book here to find out more about the themes of the ‘New Power University’.

Hybrid Teaching, Here and There

Once the first keynote was done, the breakout sessions began. I’d somehow found myself as a panelist on one and a facilitator in another, so I had my work cut out for me at this APT.

For the first one, I was part of a panel that was looking at hybrid teaching. Ably facilitated by UCL’s Martin Compton, each of us had a few moments to make some opening remarks and then we all dived straight in to audience discussion. It was reassuring to hear that not only were many institutions grappling with the challenges of teaching contexts where the moment is shared but the mode is distributed, but that also many were even trying it. There are no easy answers for this mode of teaching, but I felt that higher education was going through one of those rare periods of mass experimentation, which is where innovations and new approaches can emerge from.

My podcast co-host and I also tried to use the session to crowdsource some spoken contributions on the topic of hybrid teaching, so that we could take advantage of being in the room with others and having phones we could use for mics. However, as there was enough of a hubbub going on with the group discussions, we didn’t manage to secure any audience input for the podcast. It would take a further nine months before I could successfully produce a crowdsourced podcast episode. Still, nothing ventured, nothing gained. Watch our introduction to the podcast project in the video presentation below:

Enter ‘Transitionism’…

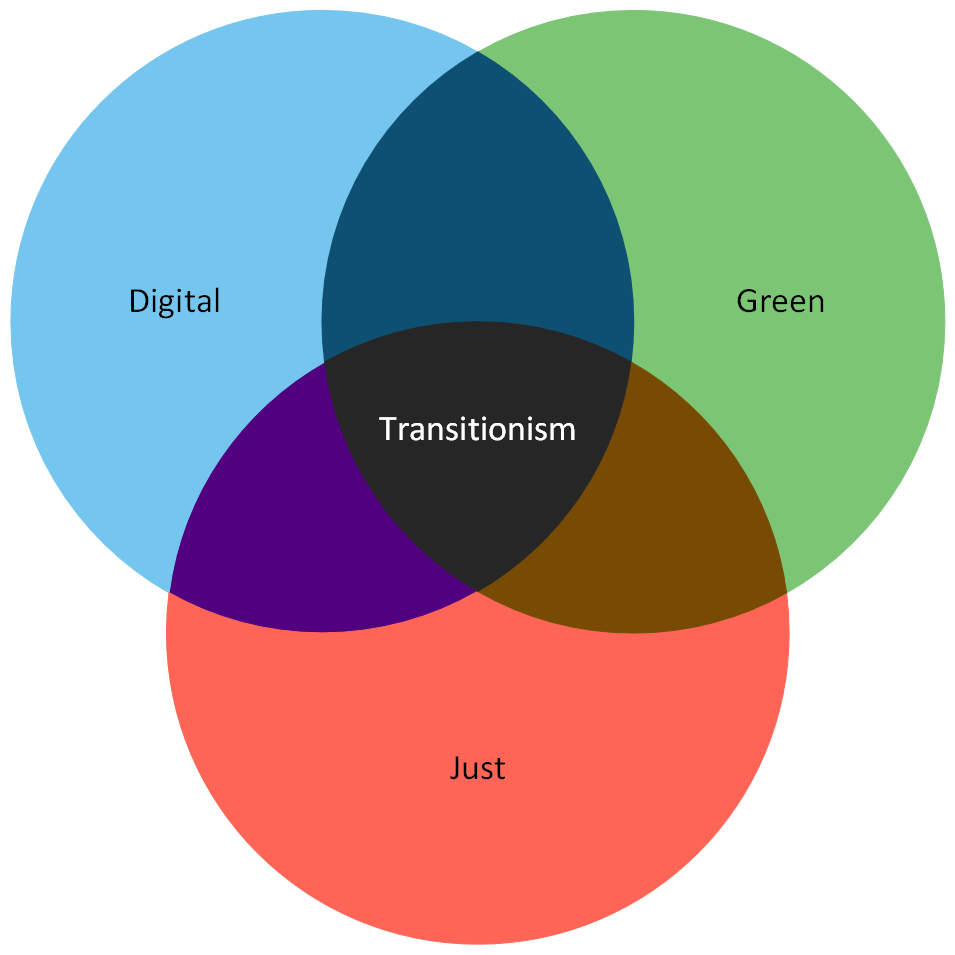

The second session I was contributing to was more of a workshop, and was an opportunity to introduce an idea to see what kind of reception it got, encouraged by and co-delivered with Julian Bream from the Bloomsbury Learning Exchange. As I’m sure many of us did, during one of the later Covid lockdowns with all that time stuck at home and with the state of the world outside seemingly in such a mess, I had a series of rather existential thoughts on the situation. At one point, triggered by something I’d watched on the BBC’s iPlayer, I ended up pondering on the nature of belief and asking myself what it was that I actually still believed in at that point in time. I ultimately settled on a new idea that neatly translated into a Venn diagram and which I formulated with the name ‘transitionism’. I won’t go into great detail on the idea (other than the brief explanation below), but will leave it here as a flag in the ground for the term on this blog. The simple belief was that – to coin a well-worn phrase – a better world is possible, but that it has to be actively brought into being.

The three parts of the Venn diagram are ‘digital’, ‘green’ and ‘just’. ‘Digital’ refers to the digital revolution that we are part way through and extols people to shape the direction of how it influences our societies so that they are impacted in a net positive way by networked and digital technologies, rather than ceding one dystopia for another. ‘Green’ refers to the great transition away from fossil fuel-run societies towards renewable powered, nature positive ones. In simple terms, a transitionist would be advocating for this rather than trying to ensure that power remains concentrated within and around those enmeshed with the oil and gas giants or even passively resisting the change. ‘Just’ refers to the imperative for more social justice in future rather than less, building on the gains of the social movements of the past and ameliorating the effects of the legacies of the social injustices that linger in our societies today. This dimension invites us to learn from our past, for example from the shift of agrarian societies to industrialised ones or from imperialism to decolonisation, and make purposefully sure that if we are to be transitioning to more digitalised, greener environments and societies, they are also more just than those of the past and that the long arc of the moral universe continues to bend towards justice.

Julian and I invited attendees to organise themselves into a seated circle. After they had settled themselves in, we then asked people to stand up (or remain standing) if they individually felt they could effect positive change in the six following prompts: in the digital world, in the environment, in terms of social justice, within their institutions, within their team or department, and within themselves. Interestingly, only two people sat down during the entire exercise, so I could tell we had an net optimistic group. As a thing to believe in, transitionism is also intended to encourage people to feel agency for effecting positive change in the face of a world beset by permacrises, so this felt like a useful start.

I then introduced the Venn diagram and spoke a little around what it represented, before moving on to tying this all in to academic practice, technology and higher education. To wrap things up, we concluded with some paired discussions and I posed a poll with the question ‘Within your roles and the work that you could do, what can you do within the three domains of digital, green and just?’, inviting individuals to commit to one single action. Responses included:

- Break the silos to bring my research and advocacy into my day job, team, institution

- Be more confident in raising the ‘just’ part of the diagram

- Reflect on my work practice based on principles rather than number of projects/tasks

- Speak truth to power. Do the right thing, not the easy or popular thing

- I commit to using the digital : green : justice frame as a wider lens to frame staff development sessions – to always have at the back of our minds a wider global purpose

The workshop had been designed to be as simple yet participative as possible. Rather than a full slide deck, the sole image I displayed in the room was the Venn diagram. Although the room clearly contained a friendly and receptive audience to the ideas being presented, it was still gratifying to see how people responded to them, particularly in seeing the agency that participants felt in being able to effect positive change in their own environments. I was also rather relieved when it was over as it felt like taking a rather bold step in a professional context – no just talking about work or work done, rather citing professional practice within a much wider context and encouraging others to take action to make change.

Stormy Friday

My sessions over, I could step back and just be an attendee at someone else’s gig. Having not had much time to think about other sessions, I ambled into one titled ‘A Perfect Storm’, a session about a tool called GPT-3 and the implications for HE assessment. I’d been keeping one lazy eye on discourse and developments around the use of ‘artificial intelligence’ (AI) in higher education for a few years now, having helped design and build a PC lab for City’s then-new MSc in AI that launched during the academic year that the pandemic hit. The discoursal signals around AI seemed to be getting louder and stronger by last summer so this session piqued my interest, even though I’d not really had much in the way of direct experience of any AI tools.

The session was run in a PC lab, so we all had access to computers in the room. There were only a handful of attendees, which ended up making for a richer conversation. Facilitator Simon Walker set the scene with a little introduction to some online ‘playground’ tools available from a company called OpenAI. MacBook on lap, I set myself up an account and started to explore this mysterious text generation tool. I’d sampled a few online text generation tools in the past, but they’d generally come up with little more than a paragraph and clearly looking machine-generated. With GPT-3, the promise was of something quite different.

I sat, therefore, on the precipice of a potential new paradigm and wondered where to go, what to do. I recalled at the turn of the millenium, the first time that I loaded Napster on an old desktop PC running Windows ME and thinking that I had no idea where to start with a whole world of apparently free music ahead of me. What was I going to use a supposedly human-like writing machine for?

After our individual deep dives over the threshold into a new world, we came back and shared stories of what we’d found. Discussion naturally turned to the topic of the workshop, which was to consider what the implications would be for higher education assessment if students could use machines to write whole essays for them that were each unique and that looked like they’d been written by them. I don’t recall what the first prompt I entered in to this text generation engine was, but I remember feeling slightly mesmerised as the blinking cursor on the screen unveiled word after word in well crafted sentences that read as if they’d been written by a human. I then attempted something a little more academic – something like a comparison between the different scientific works of Einstein and Galileo. What came back was something that read like the opening to an undergraduate essay. Not too long and not too complex, but which suggested an understanding of both scientists’ works and which made a comparison between them.

This felt like something new. Something that had the potential of rippling out and causing big changes. After our respectives forays in the prompt fields, we came back as changed people, realising that our professions were most likely going to have to start rethinking all manner of things.

Reimagining Higher Education

The closing keynote, from Dr Sarah Jones of Leicester De Montford University, was another that I’d encountered before, remotely via Digifest. As with the opening keynote though, it was full of good messages worth reinforcing. Jones’s address was titled ‘Reimagining The University’. She proposed three different models for doing this, describing them as ‘post-pandemic pedagogies’, ‘multi-disciplinary learning’ and ‘place’. This meant considerations such as not losing the benefits of the ‘Great Onlining’ that HE had experienced during lockdowns such as greater flexibility for students, and of ripping up the existing silos and boundaries that characterise our universities to build new curricula that geneuinely cross boundaries. She also spoke of our campuses becoming more meaningful places for students as they opened back up again, considering community more or factors of experiential learning that can best come from the marshalled resources of a university. It felt like a positive, thoughtful and constructive note to close the event on.

A week on from the conference, I sat at home and decided to return to OpenAI’s ‘playground’. If this thing could write plausible-sounding undergraduate essays, how could it handle fiction? Being the very hot summer that it was, I gave GPT-3 the prompt ‘Write a history of the End of the Oil Age, set in the 21st Century’, then watched as it churned out historical missives from the future. Not particularly sophisticated as examples of speculative fiction, but pretty remarkable for a computer to generate. See below for examples of what it produced.

In early December 2022, I was amongst the first million or so users of ChatGPT, OpenAI’s next product that forced the notion of AI into the public mainstream and led to so many people starting to talk about ‘Generative AI’ for the first time. By the time 2023’s edition of the APT conference came around, the whole event was about AI and its impact on HE.

Just as soon as we’d collectively emerged from the profound disruptions of the pandemic, here came the next wave, to shake higher education to its core again. Out of the frying pan, then. And into the fire.